For any other column, I’d call Gary King by his last name, but we both agreed that’s too formal for our purposes. It’s weird though, because I’ve never met Gary in person. For the past few months we’ve been penpalling and occasionally catching up on the phone.

Save for a few old photos of him in his 20s hanging from trees on the Hill, I have no idea what he looks like, although I imagine his features have rounded and his hair grown white and thin. I bet he has a long beard. He sounds like he would, at least, with his soothing bass of a voice drenched in a Wisconsin accent, the round consonants and long vowels sounding like home, no matter where you’re from.

It’s a digital-age mystery to know someone and not know what that someone looks like. But after talking to Gary on one of our calls, I stopped trying to imagine it. Instead, I just threw my prepared questions out the window and tried to, in his words, “slow down, relax and enjoy.”

Gary is a storyteller and he never starts at the beginning. He contacted me at the beginning of the summer hoping I could help him do some research about his marijuana arrest in May of 1967. He’d been a casualty of a police sting, caught with a couple of cannabis seeds in a film canister stashed in his car, although he doubts he would have been so careless.

“Of course I had marijuana,” he says. “I had a stash up on Sugarloaf. I had a stash down on Boulder Canyon, Sunshine Canyon. You know I had places everywhere, but I knew better than to keep it with me. But then again, I had just gotten back from San Francisco… ”

Before his arrest, Gary had spent the last few months in Haight-Ashbury celebrating the Summer of Love. Understandably, the details of his coastal pilgrimage are fuzzy, but he remembers just enough for a fanciful tale: He was living out of his VW bus, shared a joint (or two or three) with Jerry Garcia and somehow met Timothy Leary and took a trip. Fifty years later, the memories are flooding and filling in the blanks in his aging brain.

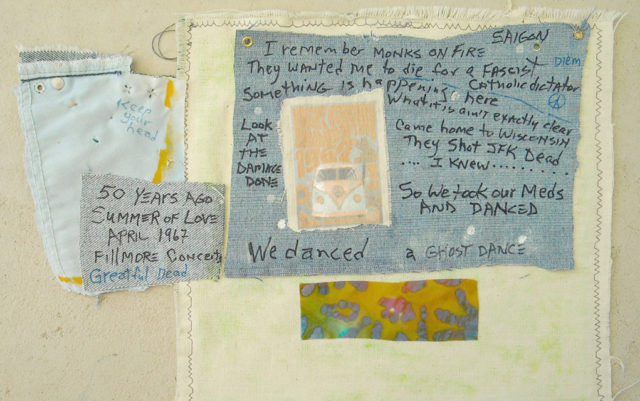

When we talked on the phone last week he told me about a series of artworks he’s making, large and small, all collages made up of jeans and beads and all sorts of hippie attire and covered with words plucked straight from his subconscious depths. Words and messages like those pictured on the art in this photo.

Each word triggers memories of stories Gary’s told me: of his reaction when he saw photos of the Vietnamese monk, Thích Quang Đuc, setting himself on fire; of skipping out on the Vietnam War, not on purpose, but because his hometown post office had burned down with his draft notice lying inside; of the time he sat stoned in a field in Boulder listening to Buffalo Springfield play carnival like songs; of hearing about the conspiracy to shoot JFK weeks before he rode high on the back of that damned Lincoln Continental.

But it’s the last part, the bit about the ghost dance, that I haven’t heard before. So Gary starts to tell me, in his roundabout way, of being the lone white man teaching at the American Indian Movement’s survival school in Wisconsin in the ’70s, one of a few locations that sought to reclaim native sovereignty and extricate their way of life, their spirituality, from white culture.

Born in the 1890s in a Paiute prophecy, the ghost dance re-gained favor in the 1970s amid the era’s increased Native American activism. In its original form, dancers dressed in white cotton would dance for five days straight, eventually falling into a trance in the process. The dance was a reflection of a prophecy that claimed that the dance was a way to gain entrance to the spirit world and, once the people were enveloped in the sky, the Earth would open up to swallow all whites and so revert back to its natural, peaceful state. The exact prophecy varied somewhat from tribe to tribe.

So, after leaving the survival school Gary would mimic the ghost dance at festivals or in psychedelic ceremonies far off in the desert. I don’t think Gary’s the kind of guy who thought much about why he was doing it, just that it felt like the right thing to do, a peaceful act of standing for something he believed in in a world that felt lost to “the Man” and his rat race.

“Do you remember in The Graduate when that guy was like, ‘I’ve got one word for you: Plastics.’? That movie came out in 1967 and it’s then that the fulcrum tipped, when more things were made of plastic than of anything real,” Gary says. “Did you know every person on the planet has plastic in their blood now? I hear it’s absorbed through your skin.”

On each piece of his art commemorating the Summer of Love, Gary has sewn back pockets and in each he’s tucked a little, hand scribed story. He warns against reading them, saying they’re not stories you want to hear.

“Terrible knowledge, or as I call it, PTSD,” he says. “Remember though, it’s not just about dropping out. It’s about turning on and tuning in. That’s what pot was always good for, at least the old stuff, a way to relax and get back to what’s real, and meaningful.”

This opinion column does not reflect the views of Boulder Weekly but rather those of the author.