There’s something for everyone in Boulder Canyon.

Starting just minutes from downtown, each curve in the road that winds through the gorge opens on an arresting landscape of dark pines and lichen-streaked rock that beckon outdoor enthusiasts looking to hike, bike and highline.

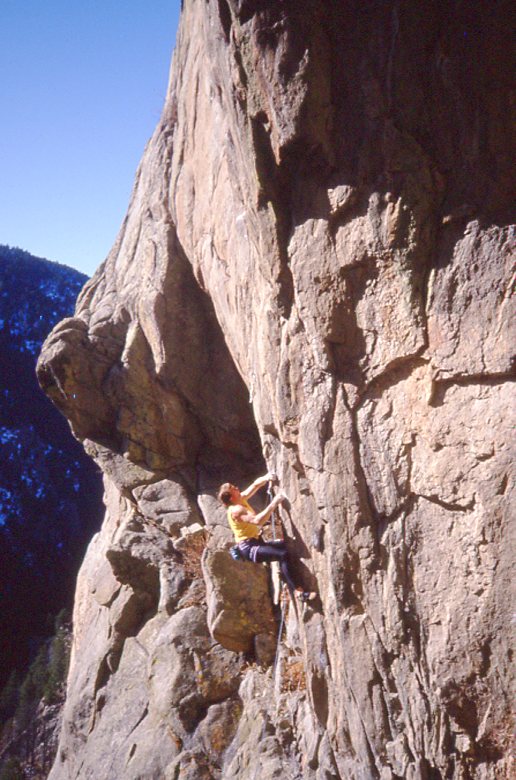

But climbing is perhaps the most popular activity along the 17 miles of road that twist through the canyon. Nearly 2,500 routes dot the ravine’s granite walls, featuring a variety of climbing styles for beginners, shredders and all the chalked-up rock-folk in between.

Some say the canyon has a reputation for soft grades and busy crags. They might be right, especially on cool weekend mornings in the fall.

But Chris Weidner, co-author of the canyon’s most comprehensive guidebook to date, Boulder Canyon, writes that “when it comes to quality, quantity and accessibility, Boulder Canyon has it all.”

It’s not just a local haunt either. Routes like Vicery, Verve, Limits of Power and Gagger have received international attention. Short approaches and proximity to the swelling Front Range make the canyon one of the most popular areas to climb in the state.

The untamed crags and elusive features of this gorgeous gully began to capture hearts and minds across the country in the ’90s when sport climbing — clipping into pre-fixed bolts — started gaining popularity. Until then, most routes were traditional — trad, as they say — where climbers place protection equipment on the way up, necessitating more technique, knowledge and gear.

There are many route-setters who deserve kudos for developing climbing through the canyon. Along with fellow trailblazers like Richard Rossiter and Bob D’Antonio, Mark Rolofson saw the ravine’s potential for sport climbing as the style gained popularity across the country.

“Sport climbing was more about pushing yourself and pushing your own limits,” Rolofson says. “The whole thing was … to look at the line and go, ‘Is this actually possible? Can I climb this?’”

Now 64 years old, Rolofson has established hundreds of routes in Boulder Canyon and written five guidebooks. Many of his routes helped establish the culture and layout of the canyon that so many climbers enjoy today.

Getting started

People traveled through Boulder Canyon well before climbers dangled on its steep faces.

The first road up the gorge was built in 1868 to meet the demand of the flourishing mining industry. The toll was $1 for a wagon, and 25 cents to giddy-up the road on a horse.

But as Boulder developed, so did climbing. The first recorded rock climb in Colorado was in Boulder in 1906 with an ascent of the Third Flatiron. In the 1940s, someone shimmied up the Third to paint “CU” in 100-foot letters that can still be faintly seen today.

Adventure seekers turned to trad climbing in the canyon around the mid-20th century, just before Rolofson started sending pitches as a young man. He grew up in Colorado Springs, where climbing was more developed than in Boulder at the time.

“From a young age, I was really kind of drawn to climbing. That was something I wanted to pursue in life,” he says. “It just fascinated me, the whole climbing thing. It was something I had to do. And it was something that I couldn’t just forget about.”

But as Rolofson was falling in love with climbing in the ‘60s and ‘70s, he says Boulder had a reputation of being “climbed out.” Many of the cracks and flakes essential for placing trad gear were already on established routes.

Despite that, his attention turned to Boulder Canyon in the early ’80s as he put up trad routes like Comfortably Numb (’82). During that time he also got a first ascent on Razor Hein Stick (’85), a slab climb Rolofson called “unclimable” until sticky rubber shoes were introduced.

Boulder quickly joined the sport-climbing movement that swept the country in the late ’80s as battery-powered hammer drills made it easier and faster to put in safer bolts. Rolofson liked sport climbing because it opened up a lot of new terrain. Before bolted routes, he says many crags had few or no climbs.

He says his establishment of Vasodilator in 1993, renowned as one of the premiere routes on the Front Range known for its multiple overhung cruxes and a smooth arête called “The Egg” at the anchors, marked the beginning of his development of sport climbs in the canyon.

“I was looking for the real striking lines that were available,” he says.

Dianne Dallin, one of Rolofson’s past climbing partners, says when she started climbing in the canyon in the mid-’80s and ’90s you had to “get your game on” and climb harder routes, the only ones available at the time. Sport climbing helped bring lower grades to the canyon and a higher level of security.

“Sport climbing allows you to put aside a lot of the dangers — but [some are] still there — and just get into, ‘Can I figure this problem out? Can I get my body to do this in the most efficient way?’” she says.

That’s not to say everyone wanted the canyon bolted.

Dallin spoke about tempers flaring at meetings between climbers, bolts getting “chopped” off sport routes and even a restraining order issued on an unnamed climber. But she says Rolofson was an advocate for sport climbing at a time when it was controversial in the local climbing community.

In a 2000 article in The Denver Post, climber and artist Steve Dieckhoff, who died in 2009, admitted to removing bolts, citing controversy over climbing techniques.

Rolofson didn’t want to get into details of the “bolting wars,” but told Boulder Weekly“a lot happened and quite a bit of it was not positive.”

While bolting remains a focus of debate in climbing ethics today, especially surrounding fixed anchors in the wilderness, the two styles of climbing co-exist.

Full send

Routes are still being established in Boulder Canyon.

Jimmie Redo has been

climbing around Boulder since

the mid-’90s and is a climbing instructor at Movement Boulder. A few years ago he teamed up with professional climber Jon Cardwell and bolted Speaks For the Trees. Redo says the obnoxiously challenging route (5.14c) might be the most continuously long and overhung route in the canyon.

“It’s pretty bloody rad,” he says. “It’s like the king line in the canyon.”

It goes to show that even with busy crowds and developed crags, there are still more routes to find.

“The canyon somehow keeps giving in the last few years, routes still keep going up,” Redo says.

Rolofson takes pride in his contributions to climbing in Boulder Canyon through helping establish classic routes like the Young and the Rackless, The Flying Beast, The Juice and Ecstasy of The People. But for him, it’s always been about quality over quantity.

Climbing is a sport surrounded by a strong ethic. The way you send or establish a route matters, not just for safety but also for integrity. Establishing routes and first ascents are achievements climbers hang their hats on.

“Being first is a big draw,” Redo says. “No one really remembers who won the National Boulder Competition in 2022. But you put up a first ascent, that’s there forever.”