We humans want the most out of life, so why shouldn’t we push to get more of what we want?

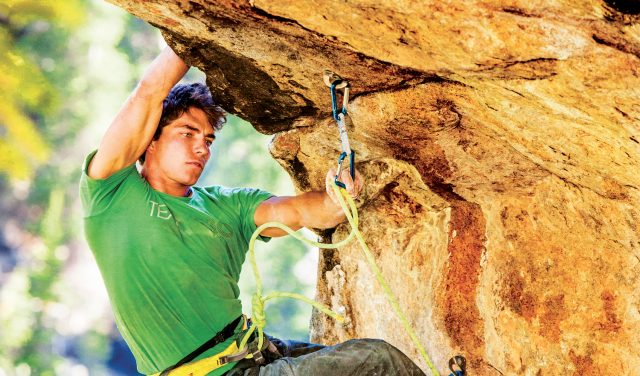

That’s what some rock climbers must be thinking. They want to enter designated wilderness in order to drill permanent anchors into rock faces, turning these wild places into sport-climbing walls.

When the Wilderness Act became law in 1964, it put wildlife and wildlands first, decreeing that these special places should be left alone as much as possible. This unusual approach codified humility, arguing that some wild places, rich in fauna and natural beauty, needed as much protection as possible.

So far, the act protects less than 3% of what Congress called “untrammeled” public land in the Lower 48. These are unique places free of roads and vehicles and most man-made intrusions that afflict the rest of America.

The Wilderness Act also prohibits “installations,” but to get around this, a group called the Access Fund has persuaded friends in Congress to introduce a bill that would, in effect, amend the Wilderness Act.

Introduced by Rep. John Curtis,

a Republican from the anti-environmental delegation of Utah, and co-sponsored by Democrat Joe Neguse from Colorado, the Protect America’s Rock Climbing Act (PARC Act) has been promoted as bi-partisan.

Yet over 40 conservation groups, from small grassroots greens to large national organizations, have written Congress to oppose the bill. Wilderness is not about human convenience, they say, it’s about safeguarding the tiny pockets of wild landscape we’ve allowed to remain.

The PARC Act directs federal agencies to recognize the legal use of fixed anchors in the wilderness, a backdoor approach to statutory amendment that even the U.S. Forest Service and Department of Interior oppose.

In a hearing on the bill, the Forest Service stated that “creating new definitions for allowable uses in wilderness areas, as (the PARC Act) would do, has the practical effect of amending the Wilderness Act. (It) could have serious and harmful consequences for the management of wilderness areas across the nation.”

Beyond the permanent visual evidence of human development, fixed anchors would attract more climbers looking for bolted routes and concentrate use in sensitive habitats. That impact is harmful enough, but the bill also sends a loud message: Recreation interests are more important than preserving the small bit of Wilderness we have left.

What’s coming next is clear.

Some mountain bikers, led by the Sustainable Trails Coalition, have introduced legislation to exempt mountain bikes from the prohibition on mechanized travel in wilderness.

Then there are the trail runners who want exemptions from the ban on commercial trail racing. Drone pilots and hang-gliders also want their forms of aircraft exempted.

What’s confounding is that climbing is already allowed in the wilderness. This bill is simply about using fixed bolts to climb as opposed to using removable protection. That’s apparently confusing to some people.

An article in the Salt Lake Tribune went so far as to wrongly state that, “a ban on anchors would be tantamount to a ban on climbing in wilderness areas.”

But now, even some climbers are pushing back. The Montana writer George Ochenski, known for his decades of first ascents in the wilderness, calls the Tribune’s position “Total bullshit.” In an email, he said bolting routes “bring ‘sport climbing’ into the wilderness when it belongs in the gym or on non-wilderness rocks.”

For decades, many climbers have advocated for a marriage of climbing and wilderness ethics. In Chouinard Equipment’s first catalog, Patagonia founder and legendary climber Yvon Chouinard called for an ethic of “clean climbing” that comes from “the exercise of moral restraint and individual responsibility.”

We don’t like to think of recreation as consumptive, but it consumes the diminishing resource of space. And protected space is in short supply as stressors on the natural world increase. With every “user group” demand, the refuge for wild animals grows smaller. Meanwhile, a startling number of our animal counterparts have faded into extinction.

As someone who loves trail running, I understand the allure of wedding a love of wild places with the love of adventure and sport. But I’ve also come to see that the flip side of freedom is restraint, and wilderness needs our restraint more than ever.

Dana Johnson is a contributor to Writers on the Range, an independent nonprofit dedicated to spurring lively conversation about the West. She is a staff attorney and policy director for Wilderness Watch, a national wilderness nonprofit.

This opinion does not necessarily reflect the views of Boulder Weekly.