The Chicago Sun-Times obituary by Neil Steinberg couldn’t have said it better: “Roger Ebert loved movies.” Considering that he reviewed thousands upon thousands of them, it was a good thing. From 1967 to his death in 2013, Ebert was the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times. He wrote weekly reviews — under deadline — for movies in current release. His first was Galia; his last was To The Wonder. In addition to his column, Ebert published no fewer than 20 books, recorded hours and hours of television with his sparring partner Gene Siskel and gave countless lectures. Roger Ebert wasn’t one to rest on his laurels.

All of this and much, much more are covered in Steve James’s excellent documentary, Life Itself, which is playing at the Boedecker Theater until August 16th.

Life Itself and Ebert’s 2011 memoir, from where the movie takes its name and a great deal of content, trace the life of Ebert from birth to death. Most knew Ebert from his popular TV show, Siskel & Ebert, but residents of Boulder will no doubt remember Ebert’s annual April visits to participate in the Conference on World Affairs.

“I lived more than nine months of my life in Boulder, Colorado,” Ebert wrote in his memoir, “one week at a time.” Ebert first attended the conference in the late ’60s as a wide-eyed critic and met what was most likely a dream for an intellectual bohemian.

There is nothing quite like the Conference on World Affairs. Speakers far and wide are invited to travel on their own dime to come and speak at free events for no pay on topics they were assigned only in the days before the panel begins. They have only their intellect and wits to rely on, and for someone like Ebert, he relished the challenge.

“At Boulder I discussed masturbation with the Greek ambassador to the United Nations,” he wrote in Life Itself. “I analyzed dirty jokes with Molly Ivins, the cabaret artist David Finkle, and the London Parliamentary correspondent Simon Horrart.” And, “There I asked Ted Turner how he got so much else right, and colorization wrong.” And a personal favorite, “From the basement of Macky Auditorium, I participated in Colorado’s first live webcast, although I’m fairly certain no one was watching.”

In James’s documentary, Ebert admits that he first attended the conference “to get laid,” but he was drawn back year after year because it offered, “world-famous scientists … filmmakers, senators, astronauts, poets, nuns, surgeons, addicts, yogis, Indian chiefs” and on and on.

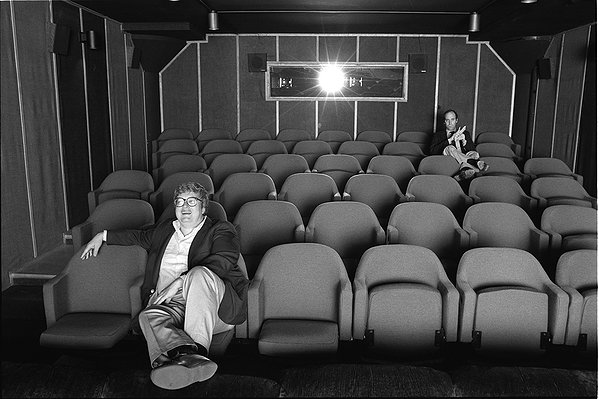

In 1975, Ebert added his own program to the conference, Ebert Interruptus. Ebert Interruptus was a democratic approach to film study, a program where Ebert and two thousand students and cinephiles sat in Macky Auditorium slowly watching movies one shot at a time, dissecting it in hopes of discovering the movie’s secrets. The process takes eight, sometimes 10 hours, over the course of a week to watch one movie. In the documentary, Ebert surmised that they found all the things that were there, and a few things that weren’t — but they found them.

His favorite movie to discuss was La Dolce Vita, the 1960 Italian film from Federico Fellini, going through it in 1979, 1983, 1994 and 2005.

Ebert returned to the Conference on World Affairs, year after year until 2010, when cancer stole his voice and the majority of his chin and Ebert gracefully bowed out.

“I won’t return to the conference,” he wrote in his memoir. “It is fueled by speech and I’m all out of gas.”

Although based on Ebert’s 2011 memoir of the same name, Life Itself should be seen more as a companion piece to Ebert’s memoir than an adaptation. For the documentary, James combined archival photography from Ebert’s youth, talking heads interviews from those closest to him and narration from Ebert’s memoir by Stephen Stanton (who mimics Ebert’s midwestern cadence perfectly). James collects segments from the plethora of footage from Ebert’s various TV shows, but it is the candid and sometimes difficult footage from Ebert’s “Third Act” that is most powerful. In 2002, Ebert was diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer, and in 2006, after a series of surgeries to remove the cancer, Ebert lost the ability to speak. The cancer continued to return and Ebert’s health problems eventually took its toll. James began filming only months before Ebert passed and the majority of the taping took place in hospital rooms and rehab centers. Ebert felt this footage was extremely important as American society often turns a blind eye to sickness and death.

Toward the end of the documentary, Ebert and his wife, Chaz, learn that Ebert will not live long enough to see the completion of the documentary, but the strength and intelligence that he approaches this moment with is both courageous and uplifting.

On April 4, 2013, just four months into the shooting of Life Itself, Roger Joseph Ebert ran out of gas for good. With Life Itself, James managed to capture Ebert’s final performance.

In preparation for the documentary, James came up with several hundred questions for Ebert to answer, one that went unanswered was, “Why did you title your book Life Itself?” The answer may seem obvious — it’s a great title for a memoir — but what personal significance it held for Ebert, died unspoken.

What does Life Itself mean? James came up with his answer, and it’s his documentary. The interviewees in Life Itself don’t directly address Ebert’s title, but each tells a heartfelt story of what Ebert’s life and work meant for them. Two in particular, directors Ava DuVernay and Martin Scorsese, share stories on how Ebert changed their lives, and not simply with a glowing movie review, but with kindness and kind words. For me, I can’t help but think of a line from Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight. In it, a down on his luck and drunk performer (played by Chaplin) rescues his downstairs neighbor from trying to commit suicide. As he nurses her back to health, she bitterly asks why she should fight. Chaplin responds, “What is there to fight for? Everything! Life itself! Isn’t that enough?” In 2002, Roger Ebert was diagnosed with cancer. Eleven years later, cancer won the war. It was during that 11-year fight that I sat in Macky Auditorium in the dark with Roger, my sister and several hundred film-lovers and had my life quietly shattered while we uncovered the secrets of La Dolce Vita. Because he fought for life itself, Ebert managed to change my life for the better. To see Life Itself is to understand how many lives he changed for the better. And not just as a film critic, but as a kind human being.

Thanks, Roger. Two Thumbs up.

Respond: [email protected]