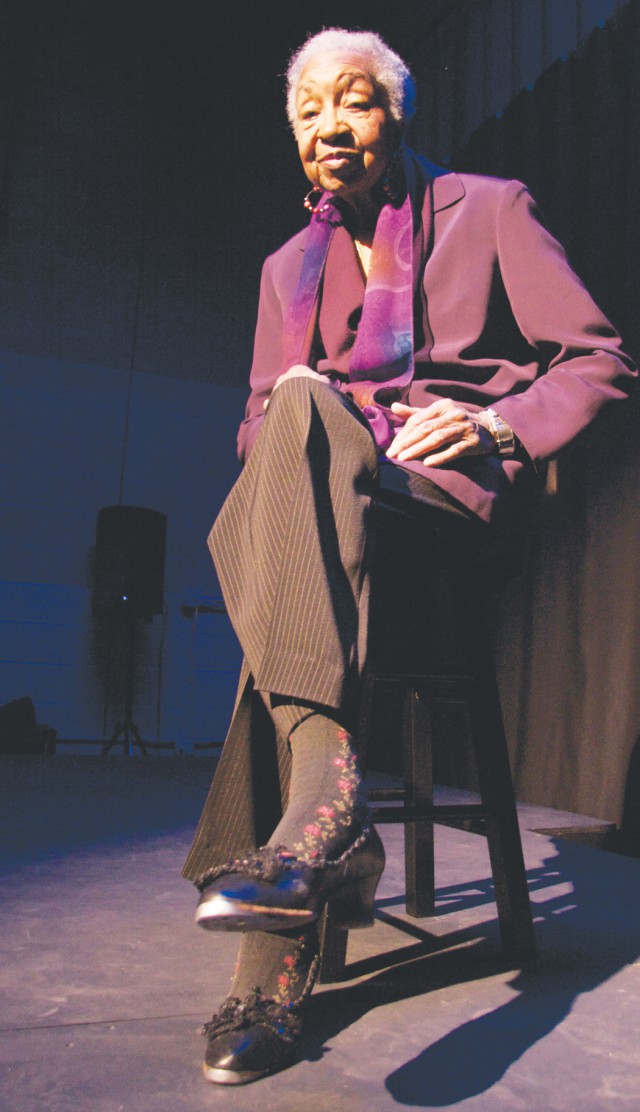

Eighty-eight-year-old Harriet Butcher vividly recalls Sammy Davis Jr. tap dancing on the stage of the Roxy Theater in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood. Butcher takes a deep breath and closes her eyes as she recalls swooning over the legendary performer.

“He tore up the show; that was big time,” she recalls.

Sharing the stage for dress rehearsals, Butcher also sang for Davis that day, and he encouraged her to stay committed to her art. She has. She continues to.

Butcher’s was an artistic childhood, spent mostly in the Five Points neighborhood. Five Points was Denver’s first predominantly African- American community, and during the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, “the Points” was the place to be for all things music, especially jazz.

Tap dance was part of the culture too, from attaching metal to school shoes to watching adolescents drop into impromptu street performances.

“In those days, everybody danced,” Butcher recalls. “At a national level, you don’t hear that much about tap dance, but it was really a part of our life. Tap was everywhere.

“These neighborhood guys would dance at the drop of a hat! Crowds would gather ’round, people would watch, cheer, and then just move on about their business. Tap dance really was a part of the community.”

But both Five Points and tap dance have faded to the background today, each but a glimmer of their glory years. Tap’s relevance is practically only historical, and Five Points is just now emerging from a crippling period of urban decay. But Butcher’s reflections bring each back to light, revealing the role of women in tap dance, historically invisible and under-valued yet integral to this uniquely American dance form.

All sparkles: women in tap

Take a minute and recollect famous tap dancers with whom you’re familiar. Who comes to mind? Gregory Hines? Fred Astaire? Gene Kelly?

Where are the women?

Admittedly, Ginger Rogers probably rings a bell, but her dancing fame came predominantly on Astaire’s arm. Through tap’s early history, women have been in the background, high-heeled, swaying and sparkling, providing the background in front of which men danced.

Growing up in Five Points, Butcher sang and danced in community performances throughout her adult life. After raising her family and retiring, Butcher collaborated with other female hoofers to form Denver’s Park Hill Tappers.

At one point, the Park Hill Tappers numbered eight women over age 65 — they danced and they danced, entertaining and teaching mostly senior audiences.

Butcher explains that the Park Hill Tappers “helped our attitude about being older, and as for these ‘wise years,’ I hope I’m leading them in a wise manner — I think it’s not what you tell them, it’s how you dance!” Boulder-based tap artist Ellie Sciarra has profiled Harriet Butcher’s story — and the personal journeys of other female tap artists in Sole Stories (currently a website, solestories.org) — a project designed to capture the voices and experiences of women in tap.

On Sole Stories, Butcher says “it’s important that women’s role in tap dancing is being recognized. I guess there’s a pleasant disagreement about how in the world they could make a movie like Tap and ignore women!” In an interview with Boulder Weekly, Sciarra describes Butcher as “inspirational and legendary … an embodiment of the beauty of tap dance.”

Female dancers like Butcher were important to the appeal and success of tap during its heyday, according to Sciarra. Even so, they didn’t often get the spotlight, nor do they often appear in history books.

Sole Stories celebrates tap’s history and the role of women in today’s efforts to reinvigorate the art form.

“I think we [women] take the edge off the tension in the performance,” says Idella Reed-Davis, a Chicago-based female tap artist. “You can breathe while we dance. … When women dance you can sit back, absorb what it is that we’re doing. You can feel. You can be in the moment with the dancers.”

Butcher agrees. “Some women want to mimic men,” she says. “I think if you can tap, make it look feminine.”

The art and history of tap

The community of Five Points fostered Butcher’s artistic life. Northeast of Denver, Five Points is one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods and a community familiar with change. Located where Denver’s downtown diagonal grid runs into the rectangular framework of eastern neighborhoods, Five Points includes neighborhoods surrounding the intersections of Washington and Welton Streets as well as 27th Street and 26th Avenue.

Although popularized today as a happy dance, tap’s legacy is deeper than the animated penguins we see today.

Constance Valis Hill, an Amherst dance professor, details tap’s legacy in her book Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History. Tap dance, according to Hill, emerged primarily from colonial America, finding its roots in the melding of music and dance of African slaves with the step dancing of Irish immigrants. At its core, tap dance is about making music with one’s feet.

In the South of the 1700s, slave laws prohibited drumming and other forms of creative expression. African slaves adapted traditional drumming and dancing circles to include percussive use of the feet, patting the body and clapping hands. During this era, indentured Irish servants also held onto cultural dance traditions, including the clogging and step dancing popularized today by Riverdance, a dramatic glorification of traditional Irish step dance.

The late 1800s and early 1900s saw tap dance blossom through further fusion and inspiration. As Hill describes, dance steps were stolen, shared and reinvented as hoofers watched each other at social clubs, dance halls and on the streets.

By the 1920s, metal taps were added to shoes to add crispness and clarity — Butcher and her schoolgirl pals followed the trend. With metal on their shoes, the children danced right through the Depression — “clip, clip, clip right up the street,” she says. They preferred tap’s percussive rhythms to playing ball during lunch breaks, and Butcher’s family would host their own variety shows for homespun entertainment on Saturday evenings.

For years, tap was the darling of vaudeville shows, according to Sciarra, and eventually made the journey to Broadway and Hollywood. Tap dance had become a uniquely American cultural fusion, one enthusiastically playing out on stages, streets and in living rooms across the nation.

‘Harlem of the West’

The 1930s and 1940s brought jazz and tap dance into direct conversation with one another. According to Hill, the emerging swing style of jazz music proved a perfect backdrop for the emerging style of jazz tap dance.

And in Five Points, the conversation between tap and jazz was loud.

In its heyday, with more than 50 night clubs and after-hours establishments, everyone was playing “the Points.” Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Miles Davis, Count Basie, Nat King Cole. The area began to be known as the “Harlem of the West,” and Rocky Mountain PBS highlighted the community in a 2001 documentary, Jazz in Five Points.

“Celebrities were part of the culture of community because of segregation,” explains Butcher.

Unable to stay in Denver hotels, these performers would play and stay in Five Points after performing on downtown Denver’s main stages. At night, the legends would jam with locals, often at Five Points’ Rossonian Hotel and Lounge.

As Butcher describes, when music is part of the “culture of community,” pianos and keyboards grace living rooms, teen bands flourish, Sunday schools rock, kids sneak off to listen to forbidden music through darkened back alley windows. This was very much the case in Five Points.

In the 1950s, Butcher worked at The Casino Dance Hall. Along with the Rossonian, it was one of the premier stops for touring jazz musicians.

Across the street from the Welton department store where Butcher once worked was the seamstress where she would take men’s trousers. Next door was the community’s primary grocer. Food markets, drug stores, insurance agents, beauty parlors and lots and lots of music and dance — Five Points had it all. Butcher says, “I just couldn’t have had it better.”

As described in Jazz in Five Points, for decades, the Points was the center of black life in the American west. During an era of intense racial segregation and discrimination, Welton Street formed the backbone of a vibrant and diverse economic community — a “city within a city.”

Instead of eating at the back doors of downtown restaurants, Five Points business owners offered black neighbors front-door service. Instead of being ushered to the balcony of downtown theaters, in Five Points black patrons could choose any seat in the house.

While the KKK burned crosses and churches around the Denver region, Harriett Butcher recalls finding a safe space for movies and live performances at Five Points’ Roxy Theatre, or simply “The Roxy,” at 2549 Welton St. The Roxy was like home because, according to Butcher, “The woman selling tickets behind the glass was one of us.”

Looking to the future

Mid-century brought decline both for tap dance and for Five Points.

Sciarra says that public appetite for tap waned as favor turned toward jazz dance and ballet on Broadway. A federal tax closed ballrooms, and dance halls and performance venues all but dried up. Television stole live audiences.

Once-vibrant Five Points dried up too, though memories remained of the close community with unlocked doors, friendly front porches, homegrown churches, fraternal organizations and boisterous house parties.

One by one, venues were shuttered, businesses languished, doors were locked as crime and drugs became more prevalent.

“[Five Points] grew too fast,” Butcher says. “Drugs came in fast and people just thought they were going to get rich quick.”

Butcher married and retreated to raise her family, her creative soul expressing itself mostly on Sundays in church choir.

Still, the ’80s and ’90s saw renewed interest in percussive dance — consider the block-busting success of Riverdance. Consider Savion Glover’s Tony Award-winning Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk — a Broadway sensation that historian Hill describes as “making tap dance cool again.”

Even so, tap dance remains mostly hidden, relegated to an occasional stage or animated film. Sciarra and Taps Are Talking, Inc. are working on a film project to honor the dance, highlighting the role of Butcher and other women tappers in the art form’s evolution. As presented in Sole Stories, Sciarra argues that there has been a consistent female presence in tap dance, albeit often in the background. In addition, female dancers, Sciarra argues, are playing an integral role in tap’s re-emerging vitality.

As for Five Points, in the early 1990s, Denver’s first light rail system connected the community to the downtown core. The community’s rich history, and the broader story of African-Americans in the West, are celebrated through the Stiles African American Heritage Center, The Black American West Museum & Heritage Center and the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library. “Juneteenth” is celebrated each summer, commemorating African- American emancipation, while the Five Points Jazz Festival also honors community tradition. Both the legendary Rossonian Hotel and Lounge and the Roxy Theatre are experiencing well-merited rebirths.

On community, connection and the arts, Butcher says, “We’ve had to fight. … Arts are important for connecting and for going further than interest in oneself and one’s own family — all the talk about having to drop music, art — no, it’s all important. Art helps us stand in decency.”

Through the years and challenges wrought by racial hatred, prejudice and discrimination, Butcher is thankful for her life experiences — especially the artistic ones.

“A life full of variety — there isn’t anything I haven’t done. I even washed dishes,” Butcher says. “It helps build character. But mostly, I like to dance.”

Respond: [email protected]