Darryl Purpose isn’t used to failure. He’s recorded eight stunning albums of folk music, enjoys a close relationship with his daughter, owns two beautiful homes overlooking Nederland, can call more than a handful of interesting folks close friends, and holds a place in the Blackjack Hall of Fame — that last accomplishment a fortunate result of being one of the fastest card counters in the world.

Success is really more Purpose’s style.

But today, on a blazing early afternoon in the first week of July, Purpose sits at a table at Salto Coffee Works with a somber look on his face.

“We’re canceling Camp Ned,” he says.

Camp Ned is Purpose’s baby, an intimate songwriter retreat he’s held for the past four years at his property in Nederland. Some of the best songwriters in the country — many of whom Purpose counts as friends — come and teach workshops for students. There’s hiking and home-cooked meals, impromptu jam sessions and late-night talks about life and songwriting. It brings together all of the things Purpose loves: songwriting, Nederland and his friends.

But things just didn’t work out this year, he says.

He hasn’t slept well, worrying himself sick the night before over whether canceling is the right choice, but in the end he knew it was. He’s told his daughter, Kari, and a few other people involved with the retreat, but he’s got more phone calls to make.

“I’m not used to failure,” he admits.

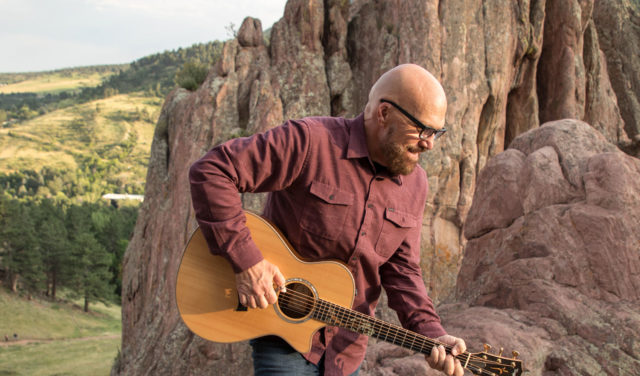

Purpose is the kind of person who’s never believed he couldn’t do something, not because he thinks so highly of himself, but simply because it never occurred to him to limit himself with doubt. He was able to pick up the guitar again after a growth on his pituitary gland wreaked havoc on his hormones and left his hands bound in splints; he survived being chased by Russian mobsters after a blackjack game in Moscow; separated throughout her childhood, Purpose repaired his estranged relationship with his daughter. In the end, Darryl Purpose always finds a way to win the day.

So the evidence is overwhelming: Purpose will find a way to host Camp Ned again, even if it has to wait a year.

“I hope so,” he says, but the wound is still fresh, his frustration palpable.

Pulling no punches

The first time I met Purpose was almost a year ago. Sitting in plump leather chairs in a different corner of Salto — a favorite morning haunt of his — he talked about losing his sister and mother earlier in the year, just weeks apart from one another. Together, he and Kari navigated the loss the best they could.

Purpose and his three siblings grew up in Southern California with a doting, “movie-star beautiful” single mother. A smart kid with a mind for mathematics and raw talent on the guitar, Purpose liked to play cards in his spare time. For Christmas when he was 16, his mom slipped a paperback copy of a blackjack strategy book called Beat the Dealer into her son’s stocking.

“I’ve since forgiven her,” Purpose likes to joke.

Though the strategy of blackjack fascinated Purpose, his passion was music. After high school he enrolled at California State College as a classical guitar major, but it wasn’t long before persistent pain in his left hand sent him to the doctor where he was ordered to wear a splint. Undeterred, Purpose continued to practice until pain in his right hand sent him back to the doctor for a second splint. His hands were tied, so to speak; Purpose made the only decision he could and dropped out of school. It would be years before he picked up the guitar again, and several more before a doctor he’d never met walked up to him after a concert one night to tell him he showed all the signs of a rare hormonal disorder known as acromegaly, caused by a mass of cells pressing on the pituitary gland. Always a big guy, the diagnosis finally explained his oversized hands and feet, his protruding brow, and the joint pain Purpose had known his whole life. (After endless trips to endocrinologists, the benign mass was finally removed in 2007.)

But at 19 years old, his college career cut short, Purpose headed for Vegas in his ’62 Chevy with nothing but his guitar, $50 and an extra shirt. It seemed like as good a time as any to try out those blackjack strategies he’d read about.

“I’d like to say blackjack is the only real job I’ve ever had,” Purpose says, but it wouldn’t be true. He had one other “real job:” selling ballpoint pens over the phone. It wasn’t glamorous, but it supported evening outings to play blackjack.

“I got a paycheck each week, went out and played blackjack — the kind of blackjack I’d learned in this book — met some people, learned more, practiced a lot. I got my 10,000 hours in well before I could legally gamble, and one thing led to another and all of a sudden I was on the biggest, baddest, most famous blackjack team of all, Ken Uston’s team.”

Uston ruled the blackjack world in the ’70s and ’80s by developing and fine-tuning techniques for team card counting. His teams were so good they were banned from casinos across the globe and often had to don disguises and use aliases to play — Purpose included.

“Oh, I wouldn’t be allowed into any casino in the world under my own name now,” Purpose admits. “By the time I was 21 I was banned from most casinos in the world.”

With Uston’s team, Purpose acted as a spotter, counting cards using the high-low strategy (every card is assigned a value of +1, -1 or 0) and signaling to another player — the “big player” — when the count was good, i.e., favorable to the player.

Purpose was capable of counting an entire deck in 10 seconds, placing him among, if not atop, the fastest card counters on the planet.

It’s not illegal to count cards in the U.S., but casinos object to the practice, if you can believe it. Card counters whose games are “too hot” will often be asked to chose another game in the casino — anything but 21.

“There’s this myth that people who can count cards are geniuses and once they know how to count cards they have like an ATM card with casinos,” Purpose says. “It’s exactly the opposite. I could teach you to count cards in an evening, but to go into a casino and make it work, as a career… it’s the opposite.”

(Purpose did try to teach his daughter and me blackjack a few weeks later, the three of us seated at his kitchen table with a high-low chart between us so we could determine the value of the cards. Purpose patiently answered our questions, only looking slightly annoyed once, maybe twice. The plan was to go to Black Hawk and actually play a game of blackjack, but Kari and I just couldn’t get comfortable with it, so we abandoned the idea, to the extremely mild disappointment of Purpose.)

He traveled the world with Uston’s team, winning and losing thousands of dollars a game — sometimes tens of thousands of dollars (he once won $150,000, which was, for a while, the largest win in a blackjack game in history). But Uston’s ego and drug addiction made him difficult to work with and within a couple of years Purpose was running his own blackjack teams. He was taken to many a back room by casino owners, saw his teammates take beatings and was once questioned by Scotland Yard — all in a hard day’s work.

“It’s very much a job,” Purpose says. “I don’t see the people in casinos as humans at all. I see it all as a cartoon and I’m stepping into the cartoon and I know my role in the cartoon and I have to play it out and do what I’m supposed to do to win.”

Purpose even brought his mom to work from time to time.

“At one point we used her as big player for when we were too well known to bet large amounts of money. We would often bring in someone else and we would signal them across the table how to play, so my mother had a stint in that. And she loved it,” he says, drawing out the O for effect. “Loved, loved, loved it. I think it was a highlight of her life.”

Purpose never fought any demons when it came to gambling; it was a job. One he was good at. One that took him around the world and let him randomly purchase a motorcycle and ride it off into the sunset. Casinos weren’t playgrounds, and they weren’t his office. In some ways, they were more like a battlefield, Purpose a professional soldier.

“I see what casinos do and I see people’s lives ruined from them. And I see no usefulness in what a casino does and I kind of hate them and I kind of use that [as motivation],” he says, “and to put an exclamation point on that, on the last night of my sister’s life she walked into a casino with $1,000 and she had written a note that if she had won a certain amount she would have paid her bills and started her life over — and she didn’t win. So she took her life that night.

“Just another reason why I don’t pull any punches when it comes to casinos, to beating them.”

All about the music

Darryl Purpose never totally abandoned blackjack, not even to this day, but he says he was “always leaving” blackjack “back then,” always looking for the next challenge or adventure.

It wasn’t until 1986 that he took his first sabbatical from professional blackjack to focus on nuclear disarmament activism. From March to November he marched alongside hundreds of other people from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in the Great Peace March. In 1987 he joined a two-week Soviet-American peace march from Leningrad to Moscow, where his band, Collective Vision, played the first Western rock concert in the Soviet Union, sharing the stage with James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt, the Doobie Brothers, Santana and several Soviet bands.

“To this day it’s my biggest show ever, although it happened years before I started a career in music,” Purpose says.

It was during his walk across the U.S. when Purpose first experienced the beauty of Colorado — Nederland, to be exact — and he told himself he would live here someday. After he began his music career in earnest, he would stop by venues like Swallow Hill in Denver and Avogadro’s Number in Fort Collins while on tour, and he knew Colorado was his heart’s home.

Never one to just talk about things he wants to do, Purpose sent an email to his fanbase asking if anyone had a room to rent in Colorado, and sure enough, a fan in Manitou Springs was able to help. By this time he had been back in the music game for nearly a decade, proudly living the life of a “starving artist,” recording his first record, Next Time Around, with little more than a guitar to his name.

“I had just been music, music, blinders on, everything was all about the music,” Purpose says. “And yet at the end of 10 years I was like, I’m not sure I can do this for the rest of my life because I hadn’t…” He pauses to arrange his words. “If I had made it a little higher, if my career had gone just a little better, maybe.”

So it comes as no surprise that when he got a call from a friend saying there was money to be made in online blackjack, Purpose jumped at the chance to go back to a game he knew he could win.

“We didn’t even have an internet connection at the house I was living at in Manitou Springs, but I went to the Starbucks in Colorado Springs,” he says. “Now this was the Starbucks run by serious right-wing Christians, sort of like being in Salt Lake City with the Mormons, a little Stepford-y but very nice. I set up my computer in there and all of a sudden I was making a couple hundred dollars a day, and then a couple thousand a day and towards the end of it I had set myself up with three computers and I remember so well in the beginning of it I only had money for one soy latte — I couldn’t get a second.

“At the end of that year I had won a million dollars in that Starbucks.”

It was success that allowed Purpose to buy a house in Nederland — one he still lives in today — and focus on music.

Camp Ned

When we first met a year ago, Purpose called his reasons for starting Camp Ned “selfish, wanting everything; wanting to bring music and songwriting to Nederland. Putting together all these things I love: friends, music, songwriting, the Rocky Mountains.”

His friends see it a different way.

Paul Zollo is a songwriter, perhaps best known for his comprehensive book Songwriters on Songwriting, a collection of interviews with greats like Bob Dylan and Paul Simon talking about their writing process. Zollo has co-written dozens of songs with Purpose, including all the songs on Purpose’s latest album, 2016’s Still The Birds.

“In this business, I’ve known so many songwriters, super famous songwriters, but I have never met anyone quite as generous as Darryl,” Zollo says over the phone on a recent Sunday morning. “It makes him really happy to be generous. He’s been so generous to me, bringing my son and me [to Nederland] so many times, but also in terms of working. He has so much respect for songwriting, for the craft of it.”

Zollo says writing with Purpose is a “joy,” an experience he sought out when he met Purpose back in the ’90s on the L.A. singer-songwriter scene.

“He’s a great composer of melodies, a remarkable guitarist and a wonderful singer — he’s got that James Taylor voice. It’s just so tender.”

For Purpose, co-writing with folks like Zollo is a part of his appreciation for the craft, a way to sharpen his own skills.

“I can be lazier with my own work than I can with a co-write,” he admits. “With a co-write I’m all in and I make it as good as it can possibly be and I get very inspired. I love teamwork and being on a team. That’s the way we play blackjack and that’s the way we write songs.”

Apparently it’s a family thing. Last year Zollo co-wrote with Purpose’s daughter, helping Kari rework a song her father had originally written for her called “Child of Hearts.”

“Not only did she ask us for help, but she was a tough task master,” Zollo says.

“One or two nights before we premiered the song [at Camp Ned’s closing concert], it must have been 2 a.m. I was exhausted and she was like, ‘no, no, no, we’re not going to bed yet.’”

Zollo helped rearrange the melody and harmony while other songwriters — Tracy Grammar, Kevin Faherty and Peter Mulvey — helped mold the lyrics. The end result, Zollo says, “was without a doubt one of the most poignant and beautiful moments at Camp Ned.

“Darryl is a guy with a lot of passion and emotion, but being a blackjack player he doesn’t always show it on the surface. I wasn’t sure how he would react to [the song]. Darryl was so moved; I could see it bubbled inside him. There were tears in his eyes.”

Purpose was the only person at Camp Ned who didn’t know Kari had reworked her dad’s song. She called her version “King of Hearts.”

“You will walk me down the aisle/ You’ll tear up and start to smile/ It wasn’t really all that hard/ For both of us to show our cards.

“The mystery of a gambler’s grace/ Has brought us here face to face/ So what you never pushed me on that swing/ This lucky girl has found a king”

Purpose says hearing it was “the best moment of my life.” It took a while for him to play it live (it felt a little like “sacrilege” to share it with strangers), but last December he played “Child of Hearts” and “King of Hearts” back to back as his closing number during a show at Avogadro’s Number in Fort Collins.

“We planned it last because I knew I wasn’t going to be able to play anything after it — and I just barely got through it,” Purpose says. “Since then I’ve played it at every show and I still barely get through it.”

A song to change the world

A few weeks after he tells me he’s canceling Camp Ned, Purpose and I chat on the phone. He’s in better spirits, though he admits he’s “taken a few steps back.” He got a call from a friend and spent six weeks in casinos playing blackjack. He seems a little sheepish about it at first, but there’s also a hint of satisfaction in his tone.

Before he hit the blackjack tables, a few of the regular teachers from Camp Ned still got together at Purpose’s to develop a plan for a Camp Ned gathering next year. Things aren’t “100 percent,” Purpose says, but they’ll know before the end of the year whether Camp Ned will live again in 2019.

“It’s not a failure,” Zollo says of canceling this year’s gathering. “Songwriters are sensitive people, hypersensitive…

“Darryl Purpose has had such tremendous success not only with music but with blackjack playing. Any perceived failure just doesn’t work for him.”

Purpose says he has new ideas, new projects to help him move forward; maybe a new album working with a new producer and some fresh local talent.

“I always thought with music, maybe someday — and I still have that idea — maybe someday I’ll write a song that will change the world,” he says.

In a life of millions won and millions lost, relationships broken and rekindled stronger than ever, it’s easy to argue that Darryl Purpose has already changed the world for everyone he’s ever met.