Under the dim light of the full moon, a group of poets gathers in a hollow of Pearl Street’s Morrison Alley. Most people come here by rumors carried from one to the next in whispers. Some find it in a drunken wrong turn, stumbling down an alleyway to find a group of madmen howling at the moon. Or maybe it’s a bartender on a lonely cigarette break or lustful lovers who just can’t wait, looking for a moment alone but are thrust into the edges of poetry instead.

Suddenly and spontaneously a howl emerges from the edge of the crowd, first gutturally from a lone man, then a full-blown chorus composed of all the standers by. “The moon! The moon!” he yells before falling into a reading of a poem.

The Full Moon Reading (as it has come to be called) is a regular but informal occasion of poetry. The gathering was born years ago between the whispers of two friends, Joseph Braun and Matthew Clifford, standing one night outside the back door of the then Boulder Café, a long-time hangout of poets and where Braun worked at the time.

“You know when you have a conversation and something comes out and you don’t know where it came from really?” Clifford asks. “I never fully know what Joseph means, but I remember one of the first things he ever said was, ‘Always digress.’ We would talk to each other like that, sort of tangentially jumping from one thought to the next; it was about having faith in your conversation partner’s mind, knowing you don’t have to affirm the thing that was done, you can just move it forward.”

So, somehow, in October 2011, the reading sprung from their minds into existence and there, in the alleyway and under the light of the full moon, it has existed ever since.

Like most of the 20 or so poets in attendance at the February gathering, the founders of the midnight poetry reading were brought to Boulder by its Beat roots. The Beat poets of the 1950s were notable namely for their rejection of poetic and social conventions. Their lifestyles and poetry, often indistinguishable, were experimental, informal, scrawled and performed in formless verses. Like the conversations of Braun and Clifford, they were disinterested in the point of it all, seeking instead to capture the spontaneity of thought and feeling.

“When I was thinking of coming [to Boulder] I was like ‘Well if Ginsberg thinks it’s cool…’” Clifford says, with a low chuckle.

In its formlessness, the reading is the living lineage of Boulder’s Beat poetics — there is no microphone, no sign-up sheet, no leader and no rules.

“You jump in when you feel compelled to. It’s totally informal,” Clifford says. “It’s a loosely regulated space and because of that it has the possibility to be generative and productive.”

The Full Moon Reading is also original in its time and place. “It’s unlike anything else going on in the world,” a man leaned over to say at one point in the night. “This isn’t a slam, it’s not a reading, it’s poetry itself.”

Set to the sounds of Friday night debauchery and the up-tempo beats of pop music leaking through the walls of the neighboring Biergarten, the poems found a natural rhythm with their surroundings. As their tempos changed, the mood shifted, too.

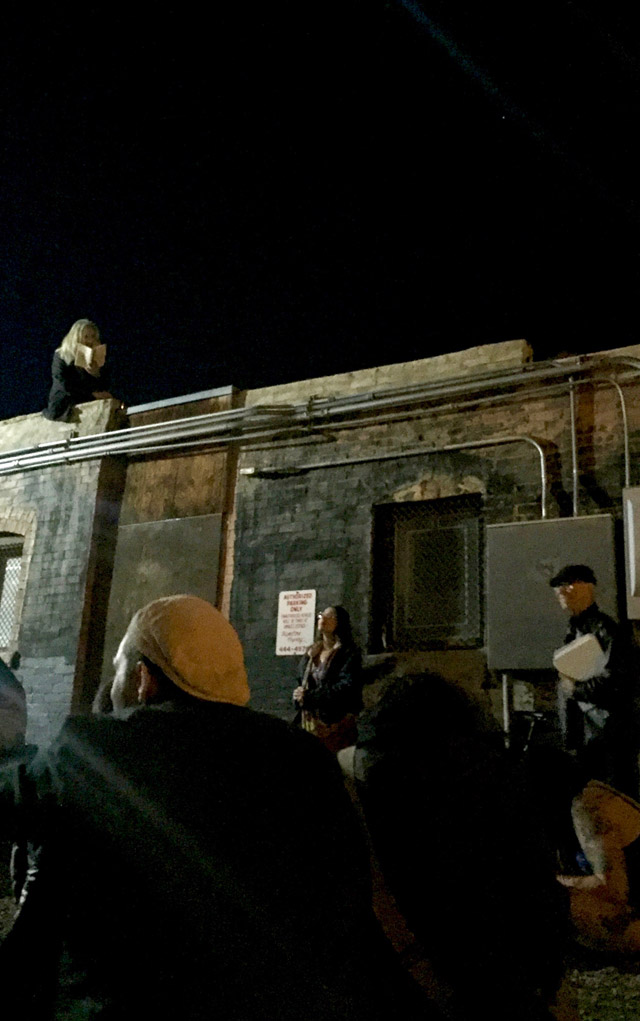

Sometimes poems were spoken softly in a closely huddled group, sometimes they were shouted from the rooftop. Once, in a particularly dramatic moment in a poem, a breeze swirled, sending pages of poetry scattering into the wind.

Among it all, one thing became clear: The idea that a poem was meant to live on a page is absurd. Poetry was never meant to be anything but read out loud.

“Importantly, this is in public,” Clifford says. “We wanted to think outside the academies or cafés, outside of places you’d expect to hear poetry.

“A lot of times we will get people who are just walking by and they come and they all the sudden are listening and they are like, ‘Wait! This is poetry?’ You can see it in their face as they start to realize what’s going on — it looks like fear. I think they’re afraid they won’t get it.”

What were the poems about? Well, sometimes the poems were political — about Trump, about what it means to be a neighbor through thin apartment walls, about the annoyance of the red, white and blue. Some were about the power of women, sex or dirty dishes. Some took cues from time and space itself, waxing about favorite restaurants turned into café-banks, the soft moonlight or dimly lit alleyways.

But what the poetry was “about” didn’t really matter at all. That night, each poem was a humble offering in itself.

“Poetry is probably the oldest art form and people seem to know it’s important — they read it at funerals and weddings, in all the big moments, you know?” Clifford says. “I don’t think people have a lot of confidence in the validity of their experiences and feelings. They’d rather not try than be wrong, but that’s one of the things that’s funny with poetry; it’s not necessarily so tied to success and failure. You can kind of do things for the sake of the endeavor.”