Rising from the foothills, a geometric sandstone building sits alone atop a mesa like a specter over Boulder.

The edifice is difficult to capture in the mind’s eye. It seems to shape-shift as it’s viewed from different angles, and the number of floors is difficult to discern. A painting hung in the hallway of one of the towers reimagines the structure as one of MC Escher’s serpentine illusion paintings.

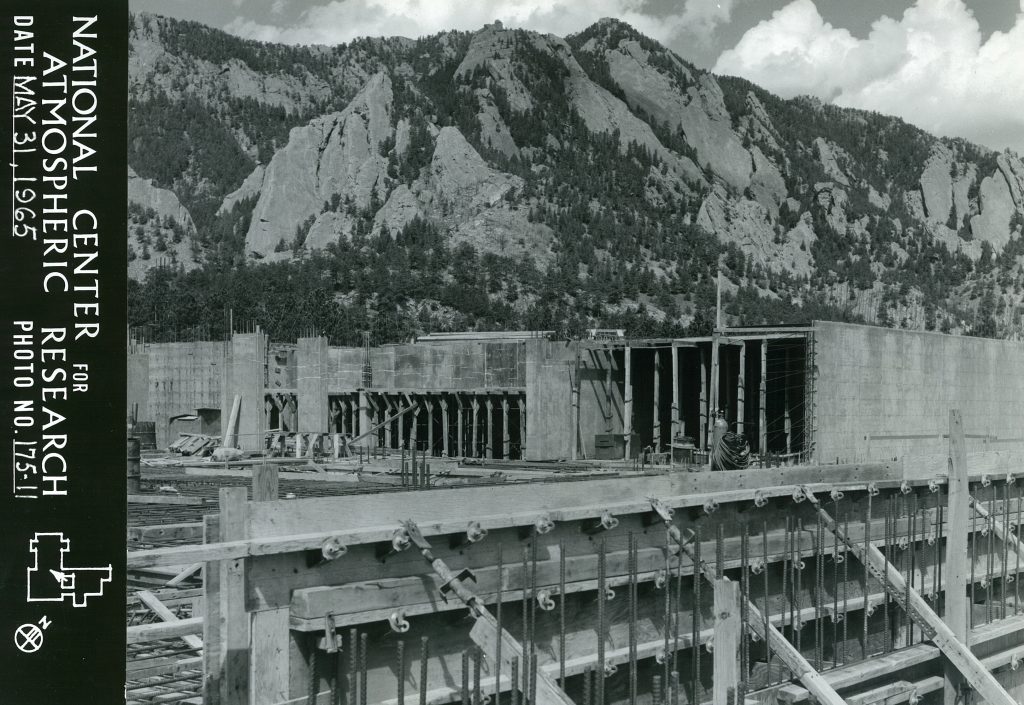

This is the National Center for Atmospheric Research’s (NCAR) Mesa Lab, a research center for the institution founded by Walter Orr Roberts in 1960 and funded by the National Science Foundation.

The building was designed by the now world-renowned architect I.M. Pei, who would later go on to design the Louvre Pyramid, the Bank of China Tower, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame among other famous works. Leonard Segel, architect and executive director of Historic Boulder, says the Mesa Lab was “the Rosebud of [Pei’s] career”

“He loved this project,” Segel says. “It made him feel connected to the ground, to expand his design skills, to explore materials he was using, materials like you’ve never used them before… I think it gave him confidence that he could take on almost any single project and come up with a grounding solution that would feel like it belonged.”

Pei described the Mesa Lab as his first “important” independent project, and having previously worked in denser urban settings, he was stunned by the natural surroundings when he arrived onsite.

“He was a three-piece suit kind of guy,” says Segel. “It was one of the most thrilling moments of his early career. He was taken out of his normal comfort zone into this spectacular, beautiful setting, and he was blown away that he had this responsibility to design a building that would feel like it fits into this environment.”

Pei traveled across the Southwest and drew inspiration from Indigenous architecture, modeling his design after Mesa Verde’s cliff dwellings. Those ancestral Pueblo homes taught Pei a valuable lesson he summarized in a 1985 interview captured in NCAR’s archives: “You can’t dominate [nature], you join it. How can you dominate nature?”

Built using concrete mixed with the same sandstone that makes up the surrounding cliffs, the lab’s color matches the hills in which it sits. Its corduroy-like texture was created using bush hammers to meticulously chip away vertical grooves on the surface that refract light and expose glimmering mica in the stone.

The structure’s meandering facade was created with a purpose beyond mere aesthetics.

“We preserved every tree,” Pei said in the 1985 interview. “The building wiggles and twists and turns to avoid damaging anything. Because those trees took a long time to grow. A tree like that may be a hundred years old, so you don’t just take it down.”

Mesa Verde influenced Pei to use what he called “powerful, elemental” forms like cylinders and squares to create the premises’ multifaceted form. “It’s complexity… and that always fits better with nature,” Pei said.

The complexity is fitting for a center that studies the atmosphere and all the earth systems it interacts with.

Today, NCAR has a budget of around $188 million, eight different labs and a supercomputing center in Wyoming. Over the years, the scientific organization has expanded into other buildings in northeast Boulder to accommodate its more than 850 staff members and needs for different labs, but the Mesa Lab remains the metaphorical heart of NCAR.

The architecture both reflects and inspires the work, its perch above the city an apt place to study the atmosphere. NCAR director Everette Joseph says the site remains a place of inspiration both to staff and to the public.

“I sit in my office and I can see a snowstorm coming in over the valley,” he says. “Sometimes you just have to stop and watch it. That is an immersive experience and an inspiring experience.”

Bringing the outside in

From the inside of the building, you can see that the corduroyed sandstone walls wrap inward.

“That’s a really important modernist sensibility is that the outdoor materials come inside and indoor space feels like it’s going right outside. There’s that sense of space that flows inside and out,” Segel says.

The lab’s design often draws comparison to a fortress or a castle, but bringing the outside world in has been essential to NCAR since its inception.

The Mesa Lab sits above Boulder’s Blue Line, a 1959 amendment to the city charter disallowing water services above a certain boundary with the intention of curbing development and preserving the open space of the foothills.

This posed a barrier for the construction of the Mesa Lab, but citizens of Boulder passed a referendum making an exception for NCAR in 1961. Roberts also laid out the need for public exhibitions in his 1961 Prospectus for a Laboratory.

“There was a lot of collaboration and work with the community to get Boulder residents on board with making this exception to allow the water services to the Mesa Lab, and Roberts in return promised that the site would remain open and be kind of a nature preserve,” NCAR archivist Laura Hoff says.

Today, the Walter Orr Roberts Weather Trail offers a hiking path connected to the lab. The middle section of the building between the two towers is home to a science exhibit, and NCAR invites the public into the space 363 days a year. In a given year, more than 100,000 people wander through the double balcony area beneath a T-shaped skylight.

“[NCAR] is part of the Boulder community, but it’s part of a much larger community as well and it is open to anybody — whether you’re interested in science or whether you’re interested in architecture or art, there there might be something for you,” says Hoff.

On a Wednesday in July, a group of 32 gathers in the lobby for a public tour as science education specialist Tim Barnes guides the group through a history of the building, NCAR’s most significant discoveries, and explainers on various phenomena. The visitors range in age and have traveled from across the state, country and world — including Connecticut, West Virginia, California and London.

Photo by Kaylee Harter

The kids on the tour are engrossed in interactive exhibits like the cloud simulator and tornado model.

Barnes, who has worked at NCAR for 28 years, makes the science approachable and engaging, comparing different greenhouse gasses to various hot sauces and coronal ejections — the solar events that cause the northern lights — to “the sun sneezing while on a merry-go-round.”

At the end of the tour, visitors ask questions about climate adaptations, how to talk to others about climate change and where to find hope for the future.

“People are happy to be here,” Barnes says. “It’s authentic. It’s rich. It’s transparent. This is open source. Like, you ask, and we can tell you.”

‘Science in service to society’

From its outset, NCAR’s mission has been “science in the service of society.”

“I have a very strong feeling that science exists to serve human welfare,” Roberts once said. “It’s wonderful to have the opportunity given to us by society to do basic research but in return, we have a very important moral responsibility to apply that research to benefiting humanity.”

NCAR science education specialist Tim Barnes leads a public tour through NCAR’s Mesa Lab. Photo by Kaylee Harter.

This pursuit, which has now evolved to “science with and for society” has manifested in a variety of ways over the years.

In 1982, the Federal Aviation Administration funded NCAR to study microbursts — a wind shear event that can be fatal during jet takeoffs and landings. Wind shear accidents caused more than 1,400 fatalities worldwide, including more than 400 deaths in the United States between 1973 and 1985, according to NCAR. The center’s research led to improved detection of the events, and no documented commercial wind shear accidents have occurred in the United States since 1994.

Today, NCAR scientists study everything from wildfire prevention to solar storms and there’s an office dedicated to education, engagement and early-career development.

Senior scientist Gabriele Pfister studies air quality, pollution, the impact of wildfires and how local and global systems interact. She collaborates with the Colorado Department of Public Health, serves on a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency panel and works to better understand what stakeholders need from research.

“I feel really fortunate that I actually not only indirectly provide information to the ultimate decision makers, but that I can actually be on this intersection, and learn from this two-way exchange,” she says.

Michael Wiltberger, deputy lab director of NCAR’s High Altitude Observatory, studies solar flares and space weather that can disrupt the power grid and radio frequencies.

“It really is science trying to understand that system, but with a direct connection … to how we live on the planet today,” Wiltberger says.

Dan Zietlow, an educational designer at NCAR who has a background in film and geophysics, supports public engagement events and traveling exhibits to help bring community members into the fold.

“We really want to avoid what we call ‘parachute science’ or ‘helicopter science’ where we just pop into the community, take what we want, extract what we want,” Zietlow says. “We want to build relationships with whatever community we’re working in, provide them with resources, to make sure we’re building an equitable relationship.”

Looking to the future, NCAR director Joseph says the goal is to continue to make the science more actionable — an interdisciplinary project that is more important today than ever.

“We are in a climate crisis and I think the urgency and the responsibility of a place like NCAR is to really do the underlying research to give the public the information they need to better protect themselves in these extreme situations, and also [to provide] information for decision makers to make decisions on how to make society more resilient, communities more resilient.”

- This story originally called Everette Joseph NCAR’s president.