Whatever the future holds and as satisfying as my life is today,” Tom Hayden wrote in his 1988 memoir, “I miss the ’60s and I always will.” Hayden was the personification of the 1960s New Left. He died on Oct. 24 at age 76. He was a leader of the radical Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a civil rights organizer in the South, a community organizer in the Newark ghetto and a major figure in the movement against the Vietnam war.

There’s a photo from the late 1970s of Hayden looking at his 22,000-page FBI file which was stacked about 5 feet high.

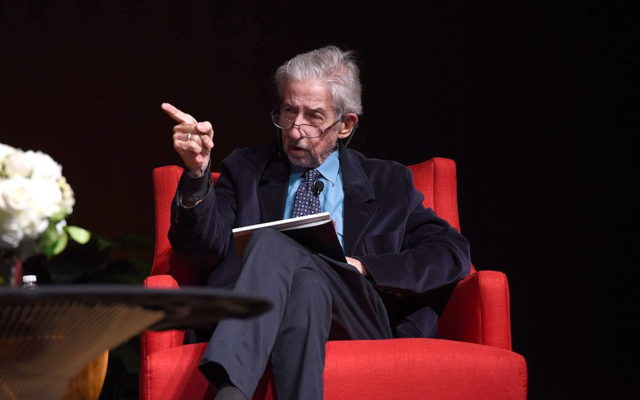

But he would remain an activist, writer, speaker and political strategist for the rest of his life.

As a 22-year-old student at the University of Michigan, Hayden was the primary author of SDS’ “Port Huron Statement,” the founding document of the New Left movement. “We are people of this generation,” the first lines of the manifesto read, “bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.”

The 1962 document attacked the costly Cold War military budget, challenged the nuclear arms race, and called for a new grassroots movement against racial discrimination, poverty and war.

It called for “participatory democracy.” Hayden would explain the concept this way many years later: “We believed in not just an electoral democracy, but also in direct participation of students in their remote-controlled universities, of employees in workplace decisions, of consumers in the marketplace, of neighborhoods in development decisions, family equality in place of Father Knows Best and online, open source participation in a world dominated by computerized systems of power.”

There were many victories. In 2012, Hayden would argue, “The ’60s movements stumbled to an end largely because we’d won the major reforms that were demanded: the 1964 and 1965 civil and voting rights laws, the end of the draft and the Vietnam War, passage of the War Powers Resolution and the Freedom of Information Act, Nixon’s environmental laws, amnesty for war resisters, two presidents forced from office, the 18-year-old vote, union recognition of public employees and farm workers, disability rights, the decline of censorship, the emergence of gays and lesbians from a shadow existence.”

In the 1970s, he helped found the Campaign for Economic Democracy (CED), a statewide grassroots organization in California. Hayden modeled CED after the Depression-era End Poverty in California (EPIC) movement. Socialist novelist Upton Sinclair created EPIC when he was the Democratic candidate for governor in 1934. The writer lost but inspired many progressives.

Hayden’s CED also worked within the Democratic Party for environmental and economic reforms.

The organization won dozens of local offices, got rent control enacted in a number of California cities, advocated for a shift to solar power and shut down a nuclear power plant through a referendum for the first time.

Hayden was elected to the California state assembly in 1982, and the state senate 10 years later, serving 18 years in all. Republicans tried to expel him twice for being a “traitor” (for opposing the Vietnam war). He served under Republican governors for 15 years and sometimes clashed with fellow Democrats who he saw as too friendly to rich donors. “He was the radical inside the system,” said Duane Peterson, a top Hayden advisor in Sacramento. Nevertheless, he managed to pass over 100 measures.

He was named legislator of the year and given similar recognitions by college student lobbyists, environmentalists, civil rights groups and animal welfare advocates.

He left office in 2000 when he was term-limited. After that, he was active as a writer, speaker, organizer and part-time teacher at several colleges. He helped organize opposition to the war in Iraq.

Hayden was an Advisory Board Member of Progressive Democrats of America which played an important role in urging Bernie Sanders to run for president. Hayden said Sanders had the potential to “legitimize democratic socialist measures, and leave an indelible mark on our frozen political culture.”

But in April he reversed himself and endorsed Clinton, arguing that Sanders was unlikely to win and that it was essential to build a united front against Trumpian proto-fascism. He said, “I’m worried that terrible friction is brewing between the two Democratic camps (Clinton and Sanders).”

I shared his concerns but felt Sanders should continue his campaign until the Democratic National Convention in order to build progressive strength in the party.

Hayden was both hopeful and concerned about a Clinton presidency. He wanted the successes of Bernie Sanders to be the basis for “a permanent progressive force.”

I wish Hayden was still around for our coming battles.

This opinion column absolutely reflects the views of Boulder Weekly.