Around 7 p.m. on the evening of Sept. 12, 2013, Marki LeCompte left her mother’s apartment at the Frasier retirement community, driving the block and a half home through water up to the running boards on her Subaru. By the time she went back to her mom’s the next morning at 8 a.m., “The west half of the Frasier retirement community looked like a war zone,” she says, mud reaching up to LaCompte’s shins.

Although her own house was protected from flooding by a sump pump, LeCompte says the flooding was incredibly traumatic for her mother and others at Frasier, many of whom lost most of their personal effects and family dam. At 93, her mother moved in with her, despite the fact that LeCompte’s house was not wheelchair accessible. After the flood, LeCompte says her mom’s health deteriorated fast as she slipped into dementia. She passed away in 2015.

Most of the residents in southeast Boulder have similar memories. The flood water came quickly, as it flowed over the top of U.S. 36 and into their streets and houses. People were stranded as egress roads were blocked and emergency crews couldn’t get in to help.

“Our neighborhood got hit really hard,” says Frasier Meadows resident Laura Tyler. “In 2013, we saw water rising within minutes from street level all the way to people’s front doors and many people got a lot of flooding. …We’re lucky we didn’t lose anyone.”

Since the flood, however, there have been competing visions within South Boulder about how the City should approach flood mitigation of South Boulder Creek in hopes of providing protection to homes in southeast Boulder before the next big flood comes. It’s been a complicated process, involving a wide variety of stakeholders with competing priorities, and one that has caused much frustration over the years. After several flood studies, the City has determined the best place for a flood mitigation project is on a mixture of open space land, managed by Open Space and Mountain Parks (OSMP), and property owned by the University of Colorado (known as CU South) just west of U.S. 36.

Some residents, those of South Boulder Creek Action Group, including Tyler, have been pushing for collaboration between CU and the City in hopes of getting flood mitigation as quickly as possible. Their mantra: “Just do something,” as Karla Rikansrud, vice president for philanthropy and social responsibility at Frasier retirement community, says.

Others, mainly those from Save South Boulder, including LaCompte, say they’re also concerned about flood mitigation, but are wary of the impacts the City’s proposed plan will have on open space land and endangered species that live there, as well as CU’s plans to develop the property that could alter the neighborhood significantly.

For years various parties have gone back and forth about potential design concepts that would impact the area differently and have differing levels of flood protection for the 3,500 people who live in the South Boulder Creek floodplain. Major decisions were set to be made this spring, before the current pandemic pushed back the timeline to early summer.

In late February 2020, during a study session on the subject, Boulder City Council directed City staff to proceed with a design concept that will include a floodwall, earthen dam and detention area on a mixture of CU and open space property to protect downstream residents in the event of a 100-year flood. (Staff’s analysis also explored 200- and 500-year options.) The plan requires the City to annex CU’s property, since it will be using some of it for flood mitigation, although what the University plans to build on the property is yet to be determined.

At an April 20 meeting, the Water Resources Advisory Board (WRAB) approved the 100-year option in a 3-2 vote, despite pushback from Save South Boulder. The Planning Board discussed CU’s annexation and flood mitigation at its meeting on May 7, although it did not take any formal action on the project. Now, the Open Space Board of Trustees (OSBT) is set to discuss the issue at its June 3 virtual meeting and provide recommendations before the City Council officially votes on a design concept after a public hearing in June.

What follows is a brief history of the property as well as an explanation of some of the competing priorities and challenges currently facing the project.

From gravel pit to CU Property

The 308-acre property now known as CU South was formerly a mined gravel pit last operated by the Flatiron Companies. Over the course of about a decade, millions of cubic yards of sand and gravel were removed from the site, lowering the area significantly. In order to protect the gravel operation from flooding, a temporary mile-long berm, which still exists today, was constructed. Although there has been some contention about whether or not the land should have been purchased by the City as open space instead, CU bought the property from Flatiron Companies in 1996 for $16.4 million. As part of that purchase, a floodplain study revealed that much of the property was in the South Boulder Creek floodplain, as were hundreds of homes in neighborhoods to the north, such as Keeywadin and Frasier Meadows.

But it wasn’t always so, says Rikansrud. “This is [Fraiser’s] 60th anniversary and when we were built it was just meadows,” she says. But as the City built Foothills Parkway and reworked the intersection at Table Mesa, it put the community in the floodplain, and Frasier even got a letter from the City encouraging the organization to get flood insurance. All of it was just an “unintended consequence as a result of the city growing,” Rikansrud says.

In 2003, the City began working on the current flood mitigation project, recognizing that a major flooding event could push water up and over U.S. 36 and into the neighborhoods on the other side like it last did in 1969. Then came the 2013 flood, confirming the predictions of earlier flood studies, and making the immediate need for flood protection at South Boulder Creek apparent. And while the neighborhoods to the southeast flooded, the gravel pit at CU South remained dry.

In 2015, the City Council approved a three-phase plan, the first of which is stormwater detention at U.S. 36 on CU’s property and the subject of controversy surrounding CU South. (The next two phases — detention projects near Manhattan Middle School, Flatirons Parkway and Baseline Road, and at the Flatirons Golf Course — have yet to be started.)

Since then, the City has been working through different design concepts trying to find one that provides adequate flood mitigation but also meets the needs of the neighborhood, the landowner, CU, open space charter requirements and Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT). Along the way, design concepts have been discarded for a variety of reasons, including a lack of approval from CU and City Council, as well as one that had to be tabled since it wouldn’t get CDOT approval, says Joe Taddeucci, director of utilities for the City of Boulder and the project manager for South Boulder Creek flood mitigation. The situation with CDOT has caused many to be skeptical of staff’s analysis and predictions about the upcoming permitting process, which will begin after a final design is chosen.

Regardless, at the study session in February 2020, staff presented three options for consideration, providing 100, 200 and 500-year protection. City Council will choose a concept to proceed with on June 16.

The ‘best’ of mediocre options

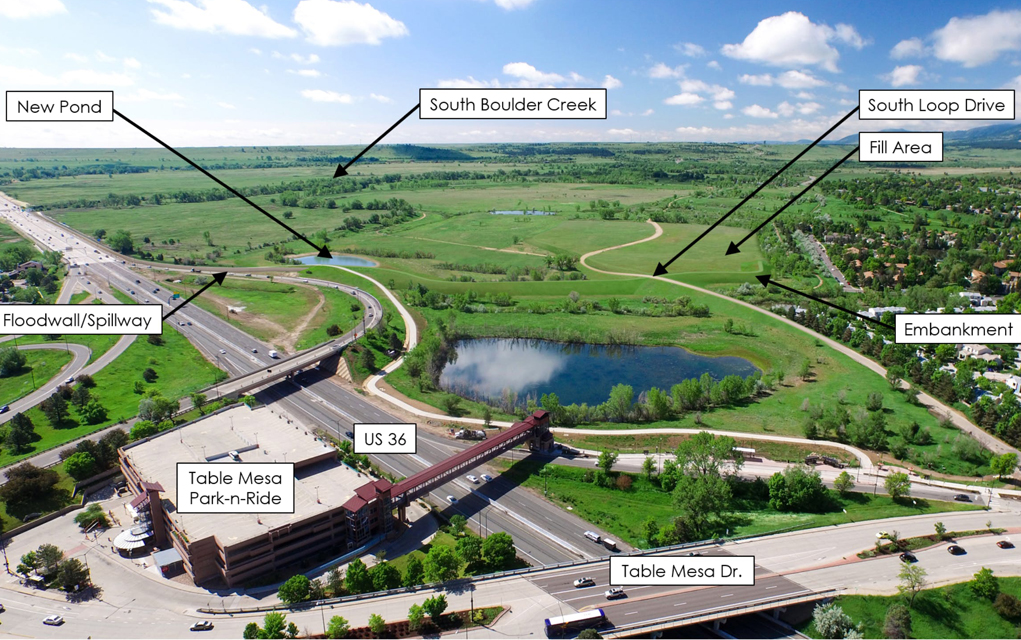

In the proposed design concept, the City would build an earthen dam parallel to Table Mesa Drive across CU South property and a floodwall to the east of that on open space land, abutting CDOT’s right of way along U.S. 36. Earth behind the dam would be excavated in order to create a detention pond in the event that South Boulder Creek floods, and outlet tunnels would be buried below the highway in order to allow the detention pond to drain.

According to City staff analysis of the current options, designing flood mitigation around a 100-year flood will produce the smallest project footprint, have the least environmental impact on surrounding open space land and wetland habitat, and will cost significantly less than the other options, mainly due to the need to fill in other areas of the property for CU development the bigger the detention project gets.

In order to build the 500-year option, which the 2018 City Council originally approved, the detention area would need to be larger, which would require more of CU’s property behind the dam. CU is expecting 129 acres of land out of the floodplain to eventually develop (see annexation section below). And both options require the City to fill in parts of the old gravel pit in order to give the University enough land to develop out of the floodplain.

Although the estimated cost for building the flood mitigation infrastructure isn’t that much more for the 500-year option compared to the 100-year option ($41 million compared to $47 million), the amount of fill it would require pushes the price up exponentially ($66 million compared to $96 million).

All of which led Council to ultimately direct staff to move forward with this plan, despite not being ideal for many.

“The 100-year option that we’ve picked is the best of a bunch of mediocre choices I would say,” says Boulder Mayor Sam Weaver. Previously, Weaver had been in support of a project that would protect the area from a 500-year flood, but he says the costs as well as the environmental impacts ultimately convinced him the 100-year option was the best path forward. Plus, he says, the 500-year option doesn’t equal five times the protection as the 100-year: “It’s about 80% give or take.”

The terms are based on statistical probability, explains Tadeucci, where the 100-year flood has about a 1% chance of happening each year, and a 500-year flood has about a 0.2% chance. Throughout the City of Boulder, he adds, building flood mitigation for a 100-year flood is the “gold standard.”

“Nowhere in the city have we done 500-year flood mitigation,” says Rachel Friend, a Boulder City Council member who was part of the South Boulder Creek Action Group before being elected in 2019. Friend also previously advocated for 500-year protection but has since gotten on board with the 100-year option.

“It’s working within the realities and what’s viable to protect health and safety,” she says.

Likewise, South Boulder Creek Action Group and Frasier retirement community have both endorsed the 100-year option as the best way to move the project forward.

“We’re big supporters of cooperation and collaboration,” Tyler says. “There’s a solution available. The science all adds up. All it requires is the City of Boulder to cooperate with you to get it done and CU throughout the years has come forward as a very willing partner.”

It also has the support of CU, which is funded by taxpayer dollars and, according to the proposal, would be gifting the City 80 acres for flood mitigation, at an estimated cost of $18 million.

“This is a very generous offer. I know that a lot of people just want the University to give the whole thing to the City, make it open space, make it flood mitigation and just go away,” says Frances Draper, senior strategic advisor of government and community engagement. “But according to the [Colorado] constitution we have to serve the state as a whole.”

Critics of the project, however, decry City Council’s backstepping, urging the City to prioritize 500-year flood protection, open space preservation and recreational value over CU’s stated needs for development as the landowner.

“The reason why this is so complex and this is so difficult to deal with in terms of the flood protection is that CU said we will give you this much property, you can have this much property and it’s right here. And so, all these engineers have been trying to horn the flood mitigation infrastructure into this space that wasn’t designed for that,” says Harlin Savage, a resident of Tantra Park Circle and co-chair of Save South Boulder. “What the City Council has done is kind of just conceded that CU owns this land so they can’t really push back too much and they’re just trying to get flood mitigation for Frasier Meadows as soon as possible.”

Competing with a mouse

When it comes to the environment, the 100-year option is expected to impact 4.8 acres of open space wetlands along U.S. 36, less than both the 200- and 500-year option. There will also be some temporary environmental impacts on OSMP land to complete construction. All of this means that in order to proceed, the OSBT will have to approve a disposal of open space land, according to the City’s charter. It also will make recommendations on the project as a whole for City Council.

At its September 2019 meeting, OSBT expressed concerns about disrupting underground water flows that nourish nearby wetlands. The board asked for engineering plans and modelling analyses in wet, dry and flood years of this flow so that whatever is built can mimic it in perpetuity.

The wetland habitat of South Boulder Creek has been a designated state natural area since 2000 for its ecosystem — a combination of riparian, tall grass prairie and wetlands, the last of which is described by the state as “among the best preserved and most ecologically significant in the Boulder Valley.” It’s also critical habitat for the Preble’s meadow jumping mouse and Ute-ladies’-tresses orchids, both federally listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (see below.) All three options for flood mitigation will impact at least a portion of this critical habitat.

“We’re talking about building a major structure that interrupts the groundwater, which basically eliminates their habitat,” says Raymond Bridge, conservation chair of Boulder County Audubon Society, which is critical of the City’s current plan. “We just don’t have a lot of land for the Preble’s jumping mouse and the Ute-ladies’-tresses. And there is no way you can replace those wetlands.”

At its September meeting, OSBT also asked for a side-by-side analysis and comparison of the current proposal and an upstream option that wouldn’t require a floodwall on OSMP land built down to bedrock, allowing the groundwater to continue to flow.

“The biggest motivation for looking at detention of flood waters upstream of the current location is that if that detention is large enough in volume, if it can withstand enough of the flood waters, then at the extreme case, you might not need to build a floodwall along Route 36 or if it were, it would be much, much smaller,” says Gordon McCurry, a hydrologist who has studied the South Boulder Creek for decades. (He’s also a member of WRAB and voted against the 100-year option at the board’s most recent meeting. However, he spoke to Boulder Weekly as a concerned citizen.)

Upstream options could also cause flood waters to pour into different areas of CU’s property, impeding on the 129 acres of land CU wants to eventually build. McCurry also suggests building detention west of Highway 93 to minimize the flood water that would eventually make it to CU South. There’s the possibility that upstream options would be more expensive, technically impossible or have increased environmental impacts and would therefore be unfeasible, McCurry admits. But they could also work better than the current proposal, and advocates with Save South Boulder say the City at least needs to look into it before committing to a plan that would damage some of the wetland ecosystem that is now a part of open space.

“The most important thing is that we consider the entire South Boulder Creek floodplain and all that property in there to the west of Highway 36 as the site for planning a flood mitigation design, and that should be done first,” LeCompte says. “And then after that is all worked out and it’s all approved and all the permits all the way up… then we go and maybe we talk about annexation, but in the meantime we can’t talk about any kind of annexation or buildup or anything with CU, and the best possible solution is to get CU to move someplace else.” (See below).

On the other hand, there are many other folks, as well as City staff, who say upstream options have been discussed for years and the current proposal is the solution that will allow flood mitigation to proceed the quickest.

“There’s no other alternative out there that’s less damaging to open space property and to the environment,” Taddeucci says.

He does acknowledge that exploring this topic further is the main reason behind the upcoming OSBT meeting in June and “if we miss something, we’d certainly reconsider that,” he says.

An open space disposal will almost certainly also be a topic of discussion at that meeting. According to the City charter, a disposal must be approved by at least three of five members of the OSBT after a public hearing and before the City Council can vote on it. If approved by City Council, a waiting period will ensue time for signature gathering to force a city-wide vote on the disposal. All of which could add to the already long timeline of getting flood protection for residents.

Furthering the timeline is the number of permits any project will need to secure, including those from USFWS, the Army Corps of Engineers, FEMA, CDOT, the state Division of Water Resources, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the City of Boulder and Boulder County (see below.)

“It’s very hard to compete with a Preble’s jumping mouse, which is adorable by the way,” Tyler from South Boulder Creek Action Group says. “I would like to posit that human life also has value.”

Concessions and controversy

The process of annexation for CU South is a bit unconventional for the City, as “We almost never do blind annexations; we usually have a site plan,” Mayor Weaver says.

But it’s hard to say exactly what CU will build out there, seeing as the University is still in the middle of its state-wide master planning process that involves the entire university system, as required by law every 10 years. Once the master planning process is complete and approved by the regents as well as the state legislature, (which won’t happen until 2021 at the earliest if not 2022) CU’s Draper says, then CU can start working on specific plans for the land in South Boulder.

“We’re not a very fast-moving organization,” Draper admits. Which is why CU is working with the City to get the property annexed now: The process of annexation will transfer the 80 acres the City of Boulder needs for flood mitigation, allowing those plans to move forward before CU’s master planning process is complete.

Regardless of what is eventually planned, Draper says the University will abide by the Guiding Principles of the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan, which CU and the City agreed to in 2017. This includes flood mitigation as well as leaving some land for trails, garden and restoration, along with playing fields for intramural sports that could potentially be shared with the community. According to the annexation proposal, potential development of the property includes faculty, graduate student and non-first-year student housing, as well as some “small-scale academic space” on 129 acres. Draper says the University has agreed to adhere to the City’s height limits for future development and won’t be building large stadiums or research facilities — “concessions that normally the University doesn’t have to agree to,” he says, given it’s a state entity.

CU does still have some hesitations about the current plan being considered, mainly that the earthen dam will wall off the property from Table Mesa only allowing for one road in and out (the current one would be elevated up and over the dam), making it less than desirable to build housing. The City and CU are still talking about other access roads, however, mainly another main entrance off Highway 93 on the south end of the property and other “lesser” entrances from nearby neighborhoods.

“We can continue to commit to put housing there, if the City will commit that there’ll be multiple entrances,” Draper says.

Weaver says his hope is that through the annexation process the guiding principles that commit the university to prioritizing housing will be written into the annexation document and become legally binding. “If we get the right guiding principles into the annexation agreement, then what goes in the future is going to be kind of shaped already in a way by that agreement,” he says.

Still, critics of the project are skeptical of CU’s development plans, which could drastically increase traffic in the area, impact its recreational value and change the neighborhood.

“This not simply CU and the City of Boulder duking it out. It’s going to have an enormous impact on the residents of Boulder,” Savage of Save South Boulder says. “And then I’m not sure people will understand that until they’re out there building it and then it will be too late.”

The next steps

All of this is sure to be discussed, in much more detail, at the upcoming public hearings both in front of the OSBT on June 3 and City Council on June 16. Prior to both of those, City staff is holding a community information virtual meeting on May 20 to discuss the flood design analysis of the different options as well as the annexation process.

“I think we’ve landed at a reasonable and actionable compromise with this,” councilmember Friend says. “Most of the work has already been done. It’s just a matter of political will at that point.”

What’s unusual about this specific project, Taddeucci says, is the level of scrutiny the public has brought to each step of the process. Having worked on public utility projects with the City since 2005, all projects with land use implications and environmental impacts tend to draw a lot of public comment, he says. But what is different this time around, “is the degree to which the comments are detailed and aimed at specific things that people perceive may be a problem or won’t work in the design or the permitting.”

Still, he’s confident that there is a way to both create a flood mitigation plan that protects residents, with minimal environmental impacts to open space, as well as an annexation agreement that meets the desires of CU. And, according to Draper, CU is ready to make an annexation deal and move to the bigger projects of permitting and designing flood mitigation.

Regardless of what option is ultimately chosen by City Council on June 16, securing flood protection is still at least a couple of years away, if not even longer. And that’s concerning to all parties involved, as climate change continues to threaten Boulder with more extreme and unpredictable weather events, including floods.

“I’m hopeful that we will continue moving this along at a good clip,” Friend says, “because it’s not hyperbole to say that lives are in significant harm’s way and we know it and we need to act.”

Endangered Species

A biological assessment, with potentially more requirements, will be necessary on any flood mitigation project at South Boulder Creek since it’s “likely to jeopardize the existence of listed species or destroy or adversely modify designated critical habitat,” according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Plus, “If somebody doesn’t like the Fish and Wildlife Service opinion, there would be potential for a federal Endangered Species Act lawsuit,” adds environmental lawyer Mike Chiropolos.

Ute-ladies’-tresses orchid

These rare wildflowers were listed as a threatened species in 1992 under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA). The tall spiral flowers are known to bloom in the summer and are easy to spot as they can stretch anywhere from 7 inches to 2 feet tall, reaching above the dense vegetation of wetland and riparian habitats where they grow. The orchids lay dormant for most of the year, sometimes for years, making it difficult to get accurate counts of how many there actually are, according to a 2005 range-wide status review of the species for USFWS.

Some people point to the fact that the flowers survived the 2013 flood of South Boulder Creek as reason to believe they will adapt to any changes brought on by the flood mitigation project. However, its scientific name, Spiranthes diluvialis, means “flower of the flood,” and the species actually benefits from periodic disturbances such as fire and flooding to prevent habitat from becoming too woody or shaded and keep competing vegetation to a minimum.

Habitat loss and degradation are the main barriers to conservation, principally “hydrologic alteration” according to Colorado State University’s “Rare Plant Guide.” Additionally, it’s difficult to transplant and reestablish these flowers.

Preble’s meadow jumping mouse

With a dark stripe of fur running down its back, this small mammal measures about 9 inches in length, 60% of which is its tail, which it uses to communicate by making drumming noises, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. Its large hind feet are adapted to jump up to four feet to avoid danger, giving the mouse its name. It’s also a threatened species under the ESA.

The mouse hibernates most of the year, burrowing in nests from September through May. When active, the mouse is largely nocturnal and can be very difficult to observe.

The Preble’s meadow jumping mouse is found in wetlands with dense shrubs and grasses along creeks and rivers spanning just 11 counties in Wyoming and Colorado. According to the USFWS, 411 miles of streamside habitat in Colorado is considered critical habitat for the mouse, offering federal protections to the wetlands surrounding South Boulder Creek.

North Campus?

Critics of development at CU South have been advocating for a potential land swap between CU and the City, exchanging 130 acres in North Boulder for CU South, so that flood mitigation can occur anywhere on the property and the entire 308 acres can become open space. Currently the land is part of a planning reserve parcel northeast of Jay Road and U.S. 36.

“I’ve been out to the planning reserve hundreds of times and it’s caked mud … It’s about as rundown biologically as you could get,” says environmental lawyer Mike Chiropolos. “It’s high and dry, which makes it appropriate for building but not a real great habitat.”

(Although there are some prairie dog colonies, which bring their own community debates.)

Chiropolos has spent his career working with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and advocates that the City applies those same principles while considering open space and critical habitat land for flood mitigation near CU South.

“The heart of NEPA is look before you leap. And that starts with cumulative impacts and alternative location analysis. So, you make intelligent, informed decisions by saying, ‘What are our options?’”

Draper says the City recently brought the idea to CU, but in order for it to be feasible the City would have to do an urban services study to annex the property before any deal could be made for CU South, a process that could add years to the timeline and push flood mitigation at CU South back even further. Plus, it would add traffic and congestion through the heart of Boulder and likely cause just as much if not more community objections, she says.

“I think that the same pushback that we’re getting in South Boulder would just be moved to North Boulder where nobody’s going to want development there either,” Friend adds. “That’s going to keep people [in South Boulder] in harm’s way for a longer period of time.”

At this time, the City is no longer considering this option.

Permits and Approvals

There are a number of permits and approvals the City of Boulder will have to navigate in order to move forward with the South Boulder Creek flood mitigation project, regardless of which design concept is eventually decided upon.

Although City staff has considered the permitting process in its analysis, some critics of the project want assurances that they are attainable for whichever design concept City Council ultimately chooses. Or, that they aren’t before a concept is ruled out.

But according to Taddeucci, without choosing a design and starting the process, the City doesn’t have enough information to bring to the different agencies. The actual permitting process can’t get underway until at least 30% if not 60% of the design work is complete, he says.

And while the list of approvals seems daunting and it’s certainly possible that the flood mitigation project won’t get through the permitting and approval process, he sees “a path through all of them.”

Below is a list of permits and approvals for the project, provided by Taddeucci and the utilities staff. The list is subject to changes as “permitting requirements may evolve once the approval process is underway depending upon agency needs and project specifics.” Explanation of each is provided by BW.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Threatened and Endangered Species Act compliance: This will require a formal consultation resulting in a biological assessment with USFWS since at least some part of the construction and permanent structures of the project is “likely to jeopardize the existence of listed species or destroy or adversely modify designated critical habitat.” It has the potential for additional requirements under the ESA, according to staff. Plus, the possibility of a federal lawsuit.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers compliance with section 404 of the Clean Water Act. Water resource projects such as dams and levees are required to go through a review process under the Waters of the U.S. rule including potential impacts to wetlands.

- Federal Agency of Emergency Management(FEMA) conditional letter of map revision and letter of map revision. The conditional letter is the agency’s comments on a proposed project that changes the characteristics of a flooding source to make sure it complies with floodplain management criteria. The letter of map revision will be obtained after construction is complete to reflect flood map changes as a result of the project.

- Colorado Department of Transportation special use permit. Although the flood wall will be built outside of CDOT’s right of way along U.S. 36, the City will need to build an underground piping or conduit system (the extent of which is based on the currently underway ground water study) to release water the pools up behind the flood wall to the wetlands on the other side of the highway. The flood wall will also tie into high ground by the South Boulder Creek Bridge to prevent water, in the case of a flood, from overtopping U.S. 36 like it did in 2013.

- Colorado Division of Water Resources consultation with the Office of the State Engineer. Water rights in Colorado and throughout the West are governed by a mixture of state and federal laws and several interstate compacts, which makes any water project that much more complicated.

- Colorado Parks and Wildlife review. Since this project will most likely affect the South Boulder Creek state natural area, it needs approval from CPW which manages the Colorado State Natural Area Program. There’s also the possibility that CPW will need to review the riparian impacts of the project in line with 1969’s Senate Bill 40, which protects wildlife resources of stream ecosystems.

- City of Boulder wetlands permit. The city code has a provision for protecting stream, wetlands and water with the intent “to preserve, protect, restore, and enhance the quality and diversity of wetlands and water bodies.”

- City of Boulder floodplain development permit. The City requires a permit for construction anywhere within the 100-year floodplain along Boulder’s 15 drainage ways “to reduce risk to life and property.” The regulated floodplain encompasses approximately 15% of the City.

- Boulder County floodplain development permit (dependent on proposed floodplain change location).