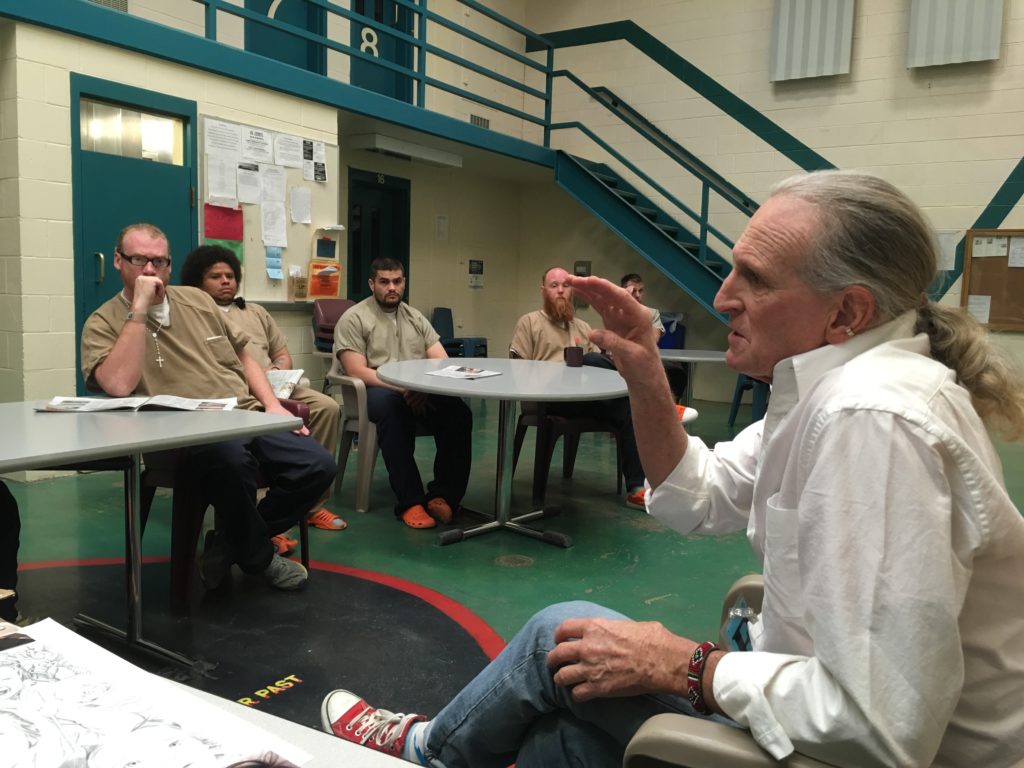

Marc Bekoff, as my grandmother would say, is a card. He’s the definition of good-natured with an easy smile. He’s quick to lovingly tease, has gray hair pulled back in a ponytail, a silver cuff around the cartilage of his left ear, socks with the PETA logo barely visible above his Converse high-tops. An original hippie to be sure.

We’re stuffing backpacks and saddlebags into shabby blue lockers in the waiting room at the Boulder County Jail.

“Remember to leave your knives and brass knuckles in the locker,” he cracks — but seriously. Leave those here.

He’s done this hundreds of times over the last 16 years — more than 700, he guesses. Marc’s retired after 32 years at CU as a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. Not one to let his zeal fade into oblivion, he comes here once a week to teach an animal behavior class to inmates in the jail’s educational and life skills programming. His is the only class of its kind for inmates anywhere in the world, save for one class in Italy — and that one’s modeled off of Marc’s class.

Our driver’s licenses come out at the check-in window. My belt keeps setting off the metal detector.

“It’s the knife. I told you. Let me get mine out of this bag.” Marc gives me a wink.

Leslie Ogeda leads us back to the module where the class is held. She’s a program specialist for the jail through Community Justice Services. She helps inmates into what’s called the “phases” program, which guides inmates through the process of changing their behaviors. There are classes in art, graphic design, mindfulness, job skills, money management and victim impact. There are parenting classes and yoga classes and classes based around addiction. And there’s Marc’s animal behavior class.

The program carries inmates from their initial decision to change their lives, through their first year after release. During that period, they have access to mental health care, and assistance with housing and food stamps. It can take months for an inmate to be accepted into this program. They’re required to finish a 25-hour independent study book, and even then the program might be too full to take them.

There are dozens of volunteers like Marc who lead classes at the jail. It’s an impressive operation.

Kyle’s not going to be able to join us today, Leslie tells Marc as we walk down a series of hallways between locked doors. She says Kyle had an altercation yesterday.

A buzzer goes off. We walk through another door.

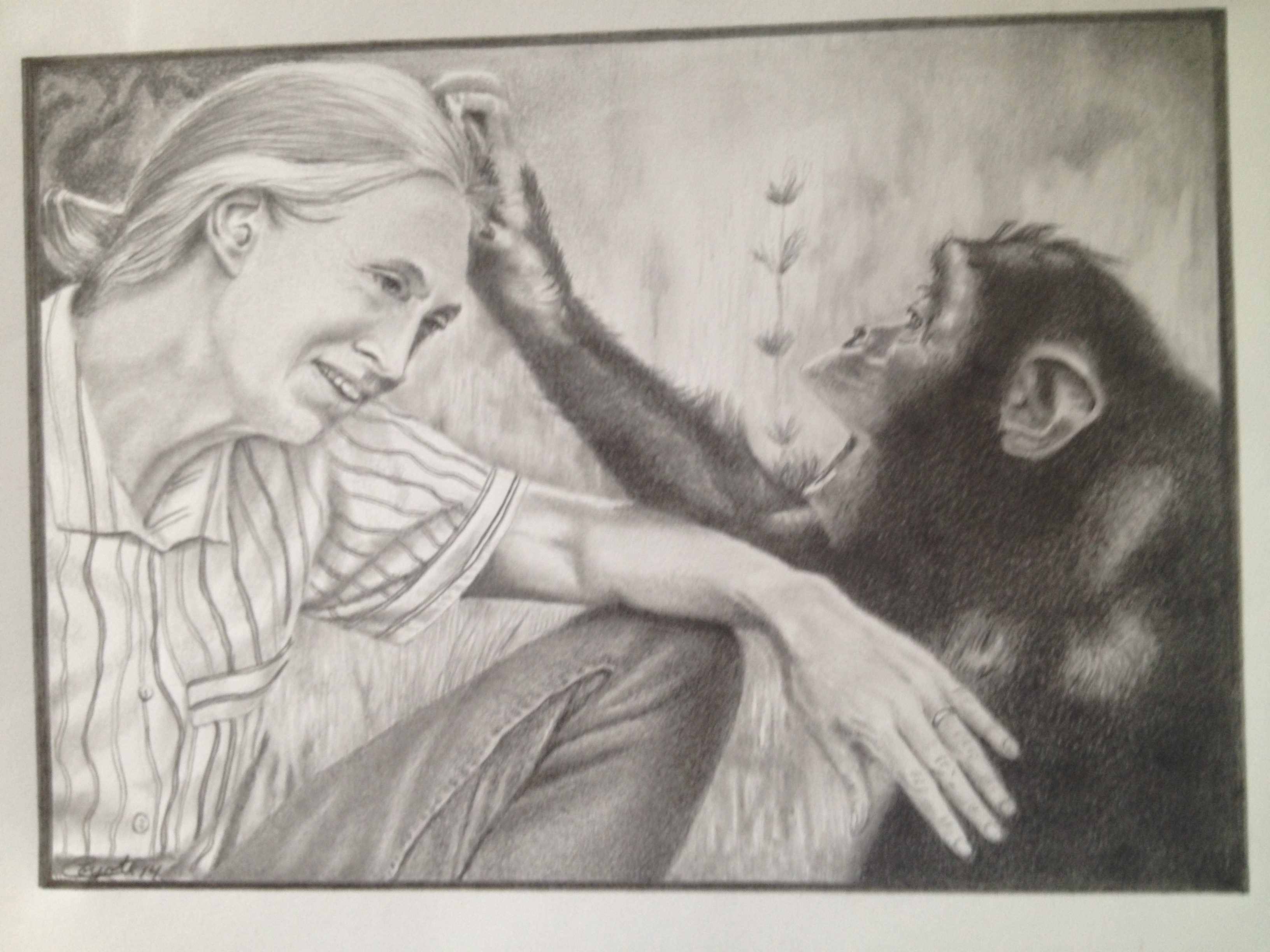

Marc is visibly disappointed, worried even. He’d mentioned earlier that Kyle had drawn a picture of a sloth especially for today’s class. Much has been made of Kyle Warner’s talent. He picked up all his artistic skill over a decade in correctional facilities, Marc says, and he currently teaches an art class at the jail. He’s been given a booth at this year’s Denver Comic Con, and Marc worries a setback like this could end all that.

Leslie assures him everything will be OK, and Marc seems relieved. He’ll ask about it again later, double-checking that everything really is OK. Marc is rooting for Kyle, but then again, Marc is rooting for all the inmates. Frankly, Marc is rooting for the whole world.

We pass a series of cell blocks, each block clearly visible through panes of glass, each virtually the same — cells grouped in twos in an upper and lower level — until we reach our block.

Everything is either bright or dull. Day-Glo orange shoes pop against khaki uniforms. Fluorescent lighting aggressively highlights off-white walls.

This is Transitions.

Home sweet home.

• • • •

On the floor is a mural of a phoenix, its red feathers set ablaze with a yellow outline. Underneath it reads, “Reborn from the ashes of our past to find our future… ”

On the main floor half a dozen tables are set up. Men mill about, getting ready for class. One of them, Brian Tyler, is the first to say hello, his voice low and soothing.

He’s tall, 6 feet or more, with a sleeve of tattoos crawling up his right arm onto his neck.

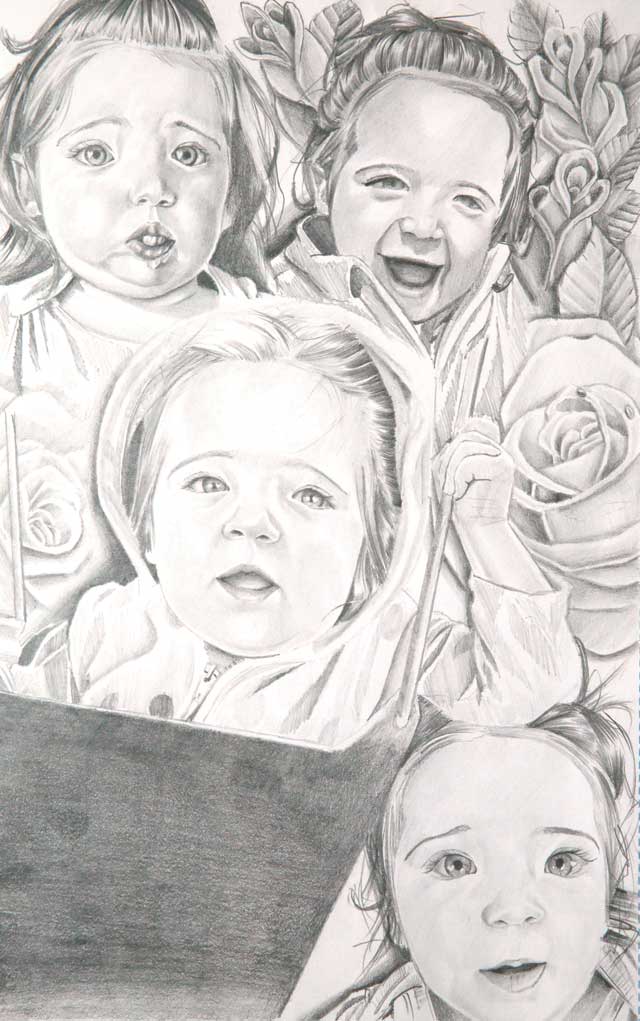

Brian’s eager to share some drawings, particularly a series of pencil sketches of a toddler with inquisitive brown eyes; no strand of hair, no eyelash ignored.

At the bottom is Kyle Warner’s signature.

The girl is Brian’s daughter, RaeAnn. He shows me the photographs Kyle used for reference, and the brilliance of Kyle’s talent rushes into sharp focus. They’re more facsimiles than drawings.

Then there’s the sloth, as promised, hanging upside-down from a branch with a look of pure bliss across its face. Marc tells me Kyle loves sloths. It’s hard to blame him; there’s a hint of wisdom in their goofy grins, like they’ve got it all figured out. Whether they know it all or absolutely nothing, they look carefree.

It’s the innocence, the purity of animals that’s so soothing — like watching a child sleep. Suddenly the world doesn’t seem so cruel.

It’s unfortunate Kyle’s not here to talk about how the sloth makes him feel.

Marc’s class is as much about human nature as it is about animal behavior. It’s part of Jane Goodall’s Roots and Shoots program, which launched in 1991 with 16 teenagers in Tanzania. Goodall — a close friend and occasional collaborator of Marc’s who visited Boulder County Jail in 2015 — wanted to connect humans with nature, with culture, with other humans. The program has spread throughout the world — some 120 countries to date. It’s offered at refugee camps, senior centers, elementary schools and, thanks to Marc, a couple of jails. Through Roots and Shoots, people learn about animals and write letters to those in other programs across the globe, discovering what it means to be a human animal.

That’s the meat and potatoes of Marc’s work and personal convictions — humans are animals. Most of his books deal with what’s known as compassionate conservation, the idea that every living thing on Earth has real value — even rats and cockroaches, the least appreciated of the “nonhuman animals,” so to speak. From this perspective, it’s easy to understand why the idea of placing humanity above all else on Earth is paramount to condemning the planet to certain doom.

During his classes at the jail, Marc shows movies — lots of National Geographic and Discovery — about animal behavior and conservation. The inmates can talk or write or draw. It’s intentionally informal.

Marc’s message is simple: We should be proud to be animals, and we have so much to learn from the behavior of other animals.

“Nonhuman animals have evolved these mechanisms for thwarting aggression, these threat signals,” Marc explains.

The bottom line, he says, is that animals in the wild can’t risk getting hurt, so they often employ appeasement tactics to diffuse aggression — like grooming one another or, as is the case with female bonobos, using sex to dispel tension. Maybe it’s less salacious than that; a lick or perhaps flattening the ears to show submission, but animals are cooperative, by and large.

And why should we be any different?

“We are not inherently warring animals,” Marc says.

He lets the group take it from there.

• • • •

In today’s class there’s no video, just conversations.

Brian is an open book. He’s unafraid to share his thoughts and emotions. It’s like candor brings him one step closer to salvation, one step closer to being reunited with his daughter, one step closer to freedom and the life he knows he can lead.

He’s been incarcerated in one way or another, in one place or another, for 27 years of his life. He’s in his mid 40s.

He brings up secure attachment, and how many of the men in jail come from broken, abusive homes. Sometimes the most reliable member of a family was the pet. And sometimes family was forged in the streets.

“That attachment that [people] have with animals or the attachment they have with other people, say gang members… when they go to the street they are looking for something that they are not getting at home,” Brian admits.

“I think that being able to recognize the behaviors and the attachments that we have with animals and seeing the attachments that we have with ourselves and the connection between us and our families and between us and our loved ones, it’s very difficult but it’s very freeing.”

In the front of the room, Aaron Waddell speaks up. He’s been in and out of Boulder County Jail since 1989 — since he was 18 years old. He’s right around Brian’s age. Once, some years ago, he and he his wife were in the jail at the same time.

“That’s the worst thing in the world: to see your wife pass you by in the hallway and you can’t say a damn thing to her.” He pauses. Clears his throat. Takes a deep breath. “Anyway, she had certain mental problems, too. She had PTSD, she’s bipolar, all clinically diagnosed with those things, plus being in jail for the first time totally wrecked her. We have two cats. We don’t have any children … she was so attached to those cats it was unbelievable. Those were our kids. They were out there and we didn’t know what was happening to them. It drove her crazy. It drove her to the point where she took offers from the DA that were out of this world, that most people wouldn’t ever have taken.”

The conversation turns to masculinity, how it binds men to behaviors that lead them here — behaviors that keep them here and bring them back once they’re free. They think about it all day, surrounded by other men who share their story.

Predators in the wild rarely kill to assert dominance, Marc reminds them — they kill to survive.

Richard Platt (“Richie”) speaks up from the back of the room. His dad died two weeks ago, and Richie is still processing. He’s bipolar. His mother went to prison when he was just 13. He’s a drug addict, and his time in Boulder County Jail is the result of a drug-fueled altercation with his father, who Richie calls his best friend. Richie lost custody of his 8-year-old son a couple of years ago because of drug addiction and mental health issues. Since 2008, he’s spent about eight months outside of a correctional facility of some sort.

“I was a wreck when my dad died, but I didn’t feel like I had to be a ‘man’ when my dad died,” he says. “I had support from these guys. It was cool to see that. I can see the stereotypes from my childhood, what was drilled into our heads when we were younger… but once you break through those roles, we’re just people. … Women and boys … it’s not that different. We all have the same emotions. It’s just about connecting. I think everything with these guys is connected, whether it be drug abuse, home life — it could be anything. We don’t feel connected to society. That’s what it boils down to.”

And that’s what Marc hopes to change.

It’s a long road with lots of unknowns. The men in the phases program are all pre-sentencing. Some of them could be out in months, while others may go on to prison. As frightening as being locked up can be, most of them express fear about those first days, weeks, months and even years after release. But this time things may be different; these men have never had support like this program provides waiting for them on the outside.

Before I leave, Brian shares a letter with me.

“I wrote this in the creative writing class and this has to do with my daughter,” he says. “I don’t know if this is what you’re looking for in your summary about what we’re doing…”

In the letter he tells his toddler that he was frightened when her mother told Brian she was pregnant. He wondered if he could be the man to guide her and teach her better than he was taught.

“So now I get on my knees and pray to the Lord and ask him for the strength to be that man. As I’m praying I hear a voice and it says, ‘All you have to do is be the best you can be. That’s all you have to do, leave the rest to me! Trust unconditionally she will love you as I do, my son. Don’t let go of this gift I give to you. I hear your prayers and I have answered you.’”

Outside the jail my eyes adjust to the sunlight and I think of a poem by Pablo Neruda: “You can cut all the flowers but you cannot keep spring from coming.”