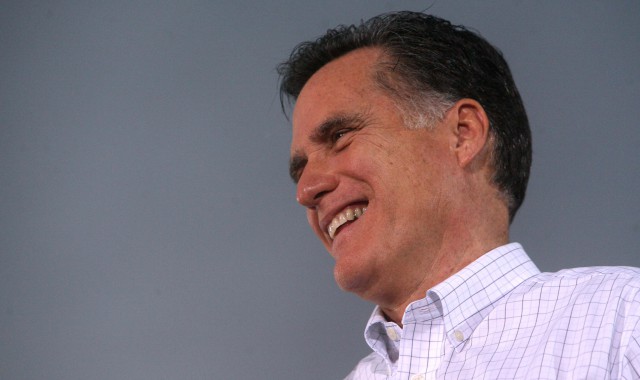

WASHINGTON — Republican presidential candidate Mitt

Romney and his wife, Ann, paid $3 million in federal taxes in 2010 on

nearly $21.7 million of income derived from a vast array of investments,

amounting to an effective tax rate of 13.9 percent, according returns

released by his campaign Tuesday.

In addition, the Romneys expect to pay $3.2 million

on $20.9 million of income for the 2011 tax year, for an effective rate

of 15.4 percent.

That’s substantially lower than the top 35 percent

marginal tax rate on wages and salaries — and much lower than the rate

than his political rivals. President Obama paid an effective tax rate of

26 percent in 2010, while former House Speaker Newt Gingrich paid a

rate of 31.6 percent. Experts say Romney benefits from a tax code that

allows investors to keep more of their income than wage earners,

particularly investors in the rarefied world of private equity.

Even among his wealthy peers — a cohort that

particularly benefits from the lower capital gains rate — Romney’s rate

is below the average 18.5 percent effective tax rate paid by the richest

1 percent, according to the Tax Policy Center.

“I pay all the taxes that are legally required and

not a dollar more,” Romney said in a debate in Tampa on Monday night

hosted by NBC. “I don’t think you want someone as the candidate for

president who pays more taxes than he owes.”

“I’m proud of the fact that I pay a lot of taxes, and

the fact is there are a lot of people in this country that pay a lot of

taxes,” he added. “I’d like to see our tax rate come down and focus on

growing the country, getting people back to work. That’s our problem in

this country right now.”

On Tuesday, the Romney campaign released a statement

from former IRS commissioner Fred Goldberg saying he had vetted the tax

returns.

“These returns reflect the complexity of our tax laws

and the types of investment activity that I would anticipate for

persons in their circumstances,” Goldberg said. “There is no indication

or suggestion of any tax-motivated or aggressive tax planning

activities. In my judgment, they have fully satisfied their

responsibilities as taxpayers. They have done so by relying on a highly

reputable return preparer and other advisers, who have in turn relied

primarily on information provided by third parties to them and to the

IRS. The end result of that process has been returns that include a

multitude of schedules, IRS forms and accompanying statements that

provide appropriate transparency and the proper payment of taxes that

Governor and Mrs. Romney owe under current law.”

The longtime private-equity chieftain hopeful

released his tax returns after pressure from Gingrich and at the urging

of his political allies, who fretted that the matter was becoming a

dangerous distraction.

The former Massachusetts governor has revealed in

financial disclosure forms in the past that he is worth as much as $250

million, but he had never released tax returns that reveal how much

money he makes each year — or how much he pays in taxes.

The release of Romney’s federal tax returns may not

provide dramatic new insight into his finances, but it is sure to fuel

the increasingly high-decibel debate about economic disparity and tax

fairness that has overtaken this year’s presidential contest and

repeatedly tripped up the Republican presidential hopeful.

Speaking on NBC’s “Today” show Tuesday, senior White

House adviser David Plouffe called Romney’s taxes “a good example … of

the tax reform we need.”

“There’s no question that we have a tax code that’s

far too complicated, far too complex, and when the average middle class

worker is paying more in taxes than people who are making $50, 60

million a year, we’ve got to change that,” he said.

The intense focus on Romney’s tax returns underscores

how the very core of his candidacy — his experience leading a private

equity firm — is also proving to be a liability in a political climate

in which class issues have taken center stage.

Gingrich has been hammering Romney over his tenure at

Bain Capital, while Democrats have taken to gleefully mocking the him

as a modern-day Gordon Gekko, the high-flying financier portrayed in the

movie “Wall Street.”

“For the average person, it raises the issue of why

some of the wealthiest people in the world are taxed at some of the

lowest rates we have,” said Joseph Bankman, a professor of tax law at

Stanford Law School. “Here is someone who kind of personifies income

inequality.”

Romney’s returns show how much he has gained from

paying the lower capital gains rate on much of his income from Bain, the

private equity firm he co-founded in the mid-1980s.

The Romney returns also spotlight the other,

congressionally mandated tax advantages enjoyed by the rich to reduce

their tax burdens, as well as how much of his wealth is tied up in funds

based in low-tax jurisdictions overseas, including the Cayman Islands.

Romney spokeswoman Andrea Saul said Monday that

Romney’s overseas investments are not tax havens. “The Romneys’

investments in funds established in the Cayman Islands are taxed in the

very same way they would be if those funds were established in the

United States,” she said.

A public perception that the wealthy don’t pay their

fair share of taxes has risen in recent years. A Pew Research Center

study last month found that 73 percent of Democrats and 57 percent of

independents cited it as their top complaint about the federal tax

system, along with 38 percent of Republicans.

The questions swirling around Romney’s finances have only furthered the debate.

“We’re learning that there are some really rich

people who are not paying that much, and that’s the way the system is

designed,” said Leonard E. Burman, a professor of public affairs at

Syracuse University and former deputy assistant secretary for tax

analysis at the Treasury Department. “There is a question about what is

the rationale for taxing capital gains at such a lower rate than other

income.”

The policy has drawn criticism from the likes of

billionaire investor Warren Buffett, who told Bloomberg Television on

Monday that while he does not fault Romney for paying only what the law

requires, the tax code should be changed.

“He makes his money the same way I make my money,”

Buffett said. “He makes money by moving around big bucks, not by

straining his back or going to work and cleaning toilets or whatever it

may be. He makes it shoving around money.”

The release of his tax returns are likely to put the

focus of the Republican primary debate even more directly on Romney’s

central pitch — that his experience at at Bain Capital gives him the

experience to lead a nation desperately in need of economic growth.

On the stump, Romney touts the investments he led in

big-growth companies such as Staples and the Sports Authority, which now

have tens of thousands of employees. His opponents, including his GOP

competitors, have portrayed him openly as a greedy Wall Street

“financial engineer” who made huge profits even when workers at firms he

acquired suffered.

A review of Romney’s record by the Tribune Washington

Bureau found a mixed record of job creation in acquired companies. For

example, four of the top 10 firms acquired by Bain during the Romney

years eventually went bankrupt. But the review found a clear record of

enormous financial gain: Of the four firms that went bankrupt, three

provided significant gains for Bain partners and investors.

The mechanics behind Romney’s low tax rate puts more

scrutiny on an industry that has been built largely on a long-standing

deduction for interest expenses, encouraging the use of debt rather than

equity to purchase and transform private companies through heavily

leveraged investments.

Private-equity executives have become among the most

aggressive at tax avoidance. “There is a contagion of tax sheltering” in

the private-equity industry, says Brad Badertscher, a professor at

Notre Dame who has studied tax liabilities of private equity firms.

“They are willing to take risks in tax avoidance that others avoid,

either for reputational reasons or because they lack the sophistication

to do it.”

Badertscher and other academic experts emphasize that

the tax breaks taken by Bain and other private-equity firms are legal.

The deduction for capital gains income was intended to encourage

risk-taking that could benefit the overall economy.

Another expert in corporate taxation says that even

management fees intended to be taxed as ordinary income are often

converted by private-equity partners into capital gains so that they are

taxed at a lower rate.

“Management fees typically consist of 2 percent of

the private equity fund’s capital,” said Sonja Olhoft Rego, an associate

professor at Indiana University. Theoretically, this fee is paid as

compensation for management services and is considered as ordinary

income for tax purposes. However, she said, her studies of the industry

show that “management fee income is often converted from ordinary income

to capital gain income” by making the fees contingent on profitability.

———

%uFFFD2012 Tribune Co.

Visit Tribune Co. at www.latimes.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services