In theory, it’s logical to assume that controlling predators by reducing their numbers in the wild would allow the numbers of prey species like deer and elk to increase — all the while, removing competition for shared resources such as big game hunting. But that’s not what a new study by Dr. Mark Elbroch, puma program director for the global wild cat conservation organization Panthera, has found.

Instead, the study, “Age-specific foraging strategies among pumas, and its implications for aiding ungulate populations through carnivore control,” recently published in Conservation Science and Practice by Elbroch and co-author Howard Quigley, suggests the current controversial strategy of increasing mountain lion killing to aid mule deer, as currently underway in Colorado, may in fact exacerbate problems for mule deer by changing the age-structure of the lion population to predominantly younger animals that are more likely to hunt deer over elk. In turn, this may lessen the ecosystem benefits provided by mountain lions.

The study specifically mentions the Colorado Department of Parks and Wildlife’s Predator Control Plans, which were approved by the Parks and Wildlife Commission in Dec. 2016, and call for the killing of hundreds of mountain lions and black bears by USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services and increased hunter take in an effort to increase mule deer populations on Colorado’s Western Slope. There are numerous lawsuits challenging various aspects of the plans at both the state and federal levels (see Boulder Weekly’s “Off Target” series.)

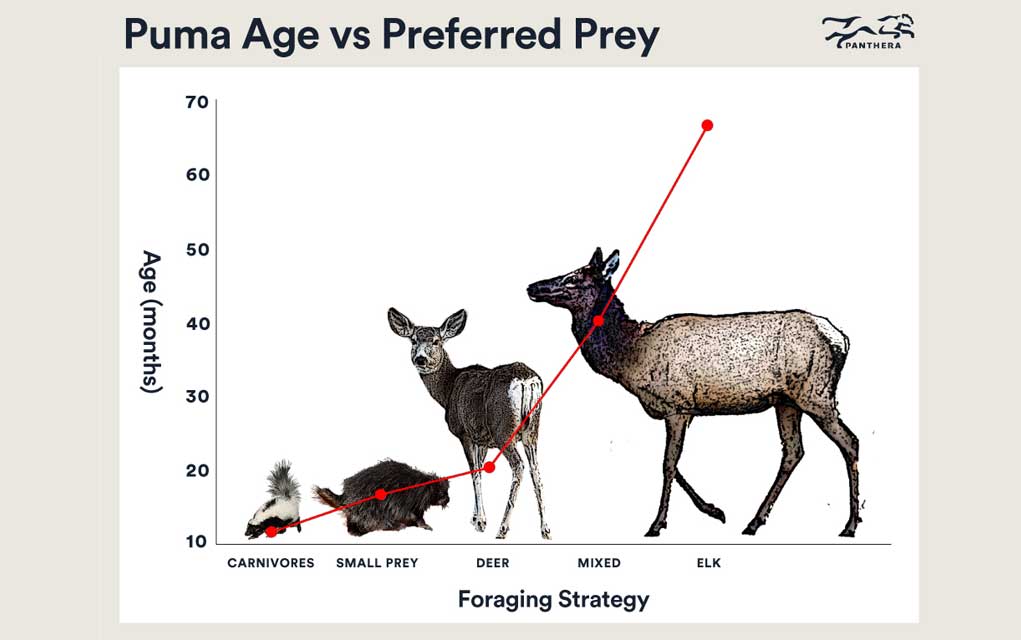

Elbroch told BW this research was different for him because he didn’t initially ask any specific questions, adding that because of the type of analysis he did, he was able to allow the data to speak for itself. The process allowed him to determine what cougars were eating at what ages. The result was startling in its simplicity. “A remarkable 78 percent, which in ecology is unheard of, was explained by only one factor: age,” he says. “The older the cat, generally, the larger the prey it specialized on.”

“I love when things are simple like that,” Elbroch says.

Referring to a visual graph produced for the study, Elbroch points out that mountain lions progressively ate larger prey as they grew older, specializing in deer when they were two to two-and-a-half years old. After that, he says, the cougars he studied split their attention between deer and elk. “And by the time they’re five and five-and-a-half,” he says, “they’ve really transitioned to a predominantly elk diet.”

“Once I got to that point, I started to think about its implications,” Elbroch says.

Part of the reason that Colorado, along with other Western states, allows the hunting of mountain lions is to try to maintain big game populations at a certain level, Elbroch says, which is always undefined because no one really knows the numbers of the actual populations. He says this killing of predators is done in an attempt to help mule deer, which are struggling in the Rocky Mountain West. Elbroch adds that by knowing that heavy harvest (hunting) of mountain lions radically influences the age of those animals on the landscape, he realized a potential analog with CPW’s predator control plans.

“I was like, geesh, isn’t it ironic that maintaining a three-year-old [mountain lion] population means you’re actually reducing the variation in kinds of prey they eat, and you’re holding at a population that may be predominantly eating deer?”

“The irony wasn’t lost on me,” Elbroch says, referring to the implications of his findings for CPW’s predator plans. “But I’m also quick to point out that this is one study, it was not a huge number of cats,” adding he’d love to see more researchers replicate his findings, including CPW.

In response to e-mailed questions, CPW was quick to criticize the sample size and location of Elbroch’s study (13 cougars were studied and the study was conducted in the Yellowstone ecosystem.) CPW says there are a number of variables to consider in these different contexts, calling the comparison of Elbroch’s findings to Colorado, “a stretch.” But despite the obvious differences in context, CPW concedes Elbroch’s study may provide evidence that cougars shift to larger prey as they get older.

However, CPW claims this finding isn’t consistent with data from two of its studies in Colorado, which found mountain lions killed both fawn and adult deer and elk calves in nearly equal proportions, and that lions killed a large number of small prey within the urban-wildland interface and deer fawns and elk calves during summer. “Mountain lion predation on elk was limited and predominantly by male cougars,” according to CPW.

For those reasons, CPW asserts that instead of a cougar’s age, “The location of a lion’s home range relative to prey availability was a much better predictor of prey selection than lion age,” adding its research demonstrates harvesting fewer lions and leaving more older lions on the landscape does not equate to growth in mule deer populations.

Elbroch says that although CPW is right that any comparison between his findings and mountain lion research in Colorado must take into account how the two locations differ. But he adds that the agency’s responses are just reporting what it saw at a glance, and were not the result of CPW having conducted any similar analysis to what he did. Once the differences in context are accounted for, Elbroch adds, then researchers can see whether the pattern holds true across systems. “They of course didn’t do this themselves, so can’t compare what they found in Colorado in their state-led studies to mine — they would need to account for differences in prey availability first,” he says, “Thus their arguments do not carry scientific weight.”

Elbroch emphasizes that his study, encourages additional research, adding that to do this requires a lot of fieldwork. He says he and his colleagues want people to follow up with more research, not discount their study because it’s from a different context and includes a smaller sample size. “The scientific approach is to repeat the study well, with open mind, and to account for differences in prey availability so that the studies are comparable, and then to see what comes out at the end of the analysis,” Elbroch says, “That’s what we need to push our understanding of predator-prey dynamics further — open minds, and scientific rigor.”

He adds he and his colleagues raised CPW’s predator control plans as an example of management where the goal is to aid mule deer, “but that if this pattern holds true, they may in fact be shooting themselves in the foot,” he says.

Elbroch says the more researchers study mountain lions, the more they realize they contribute far more beneficial ecosystem-wide services than researchers ever expected. Researchers like Elbroch have just begun to uncover what mountain lions do for our ecosystems. And given their large range from here all the way to southern South America, he says,“they have a huge impact on biodiversity across that range, which is stunning and startling and exciting.”