It was dusk by the time votes were counted on Tuesday, Jan. 24. A representative for the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) tallied the results from inside the Starbucks while a dozen necks bent toward smartphones streaming the results from the parking lot. The federal agency adjudicates labor rights violations and administers union elections across the country. With a mix of guarded excitement and hope, the workers watched on, clearly cold, huddling, but confident.

Thirteen yes votes, two no votes. Baristas at the Baseline branch (2400 Baseline Road) of the world’s largest coffee chain won the election. They are the latest of nine Starbucks locations in Colorado to join the Workers United labor union and the first in Boulder to do so. One employee then another raised a fist before the chill set in. Drinks at a warm bar came next. This was a moment seven months in the making.

“It honestly began with someone telling a joke last summer,” says Holden Sheftel, 31, a shift supervisor at the store who has worked with the company for more than seven years. “We’d seen cuts to our hours and minimal increases in wages, even as the cost of living and inflation went up,” Sheftel says. One of his colleagues remarked that they should start a union. “Then we started to speak more seriously about it.”

A burgeoning movement meets a headwind

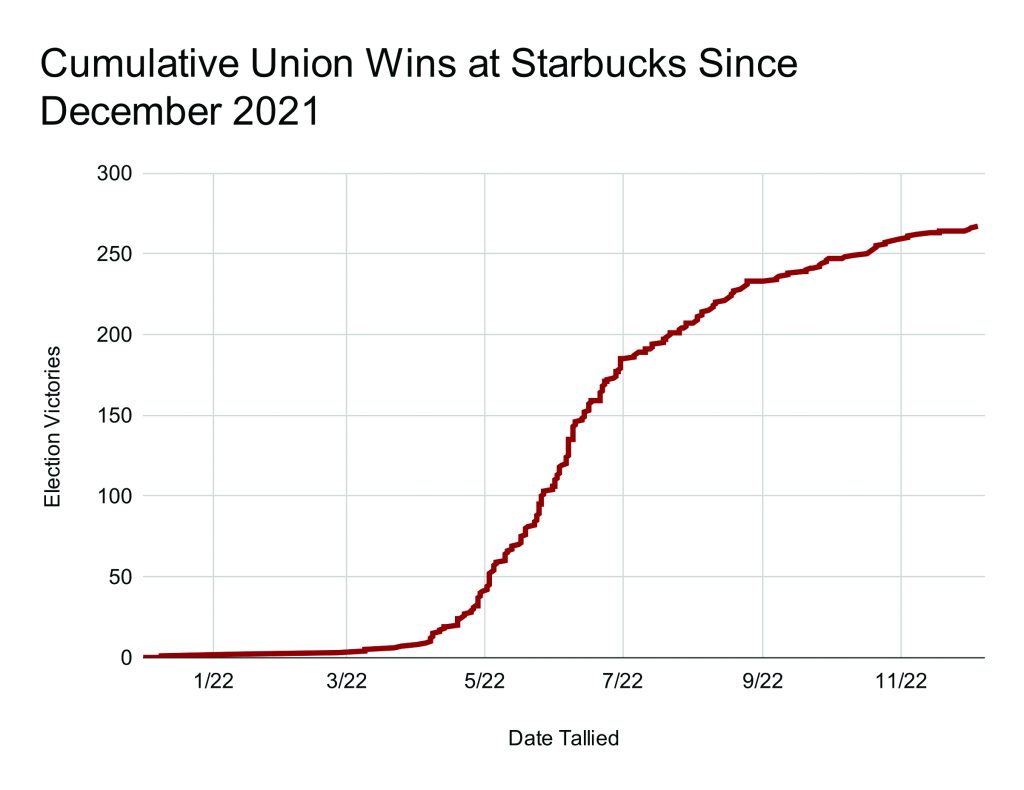

Six months prior in Buffalo, New York, workers organized the first successful union at Starbucks in the company’s history. Their complaints — low pay, cuts to hours and lack of benefits — reverberated through the coffee giant, as did the workers’ victory. By the end of 2022, more than 270 stores had unionized.

These wins underscore a tectonic shift in how labor organizing is viewed in the United States, particularly among younger workers with a heightened sense of financial insecurity. Support for unions is at its highest since 1965, according to a Gallup survey published last August. But while cultural tides are changing, labor organizers are still swimming against the current. Those 270-odd Starbucks locations account for roughly 3% of the 9,000-plus stores operated by the brand, and the rate of successful union elections has slowed considerably since last spring.

Organizers, as well as U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, believe Starbucks’ hard-nosed approach to combating unions has frightened many workers from banding together. Sanders cited more than 500 complaints of labor rights violations filed against the company with the NLRB.

Starbucks closed a unionized store in Colorado Springs last October in a move representatives for Workers United characterized as retaliatory, while in Denver, Colorado Public Radio reported on the circumstances surrounding Monique McGeorge’s termination last May. The Starbucks employee was ostensibly fired for dropping a cake pop on the store counter and then handing it back to a customer, violating company food safety protocols.

Workers United believes McGeorge’s firing was a response to the East Colfax location’s union election. Starbucks denies the allegations.

‘We’re hoping to make a statement’

In spite of the risks, the Starbucks baristas on Broadway and Baseline are undeterred. “We’re looking forward to having more control over what happens in our store,” says Rachel Frey, 22, a shift manager and organizing committee member.

Sheftel explains the appeal of collective bargaining as a matter of survival for him and his coworkers. A living wage in Boulder is $21/hr for a single adult working full-time with no children, according to MIT’s living wage calculator. Current job listings at Boulder County Starbucks list starting wages at $16/hr — $2 less than McDonalds.

“But it’s not just the amount of money people are making,” Sheftel says. “The reduction of hours means less people on the floor doing the same amount of work. It’s stressful.” Cuts to hours have cascading effects across the store, he adds. Workers who are also enrolled at university found it increasingly difficult to get shifts that accommodate their school schedules. Fewer hours mean less money for groceries and rent, and for older employees, it can mean losing eligibility for benefits like Starbucks’ healthcare plan.

Mostly, Frey says, the decision to unionize came down to exhausting all other options: “We met with our district manager to try and address some of these problems. We were told that they didn’t have a way to address them.”

Starbucks issued a statement on Jan. 23 in response to the impending vote. “From the beginning, we’ve been clear in our belief that we are better together as partners, without a union between us, and that conviction has not changed,” a company spokesman told Boulder Weekly over email.

The election win is both a beginning and an end. It marks the culmination of dogged organizing and inaugurates a new phase for these coffee shop workers, the negotiation of a collective bargaining agreement over wages, hours and store policies, which can take months in some cases.

“We’re hoping to make a statement,” Sheftel says. “We’re hoping to inspire other Starbucks in the area.”