What’s in a name? When it comes to marijuana strains, results vary — sometimes spectacularly. And according to a story in Marijuana Business Daily, the marijuana industry has about had its fill of it.

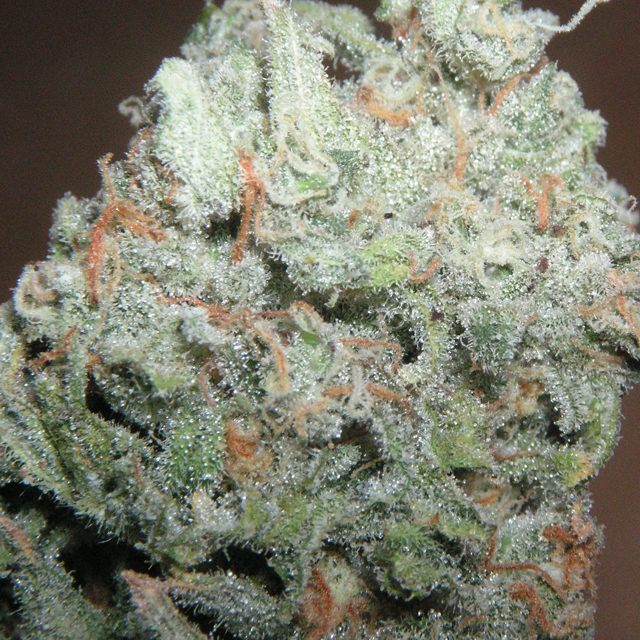

There are thousands of marijuana strain names. Each one is supposed to refer to a specific type of pot, but frequently pots with the same name differ dramatically in terms of genetics and the types of cannabinoids they contain.

As a result, increasing numbers of industry participants are starting to view strain names as “unreliable indicators” of a plant’s genetics and cannabinoid makeup.

Moreover, plants — even within the same strain — “don’t always come out the same,” according to Autumn Karcey, president of Cultivo, a Los Angeles cultivation consultancy.

“I can take Sour Diesel from four of my friends and I can take Mimosa or Clementine from multiple people, and if I genomically test it, it’s going to be drastically different from person to person unless they all have the same cut,” she added.

Sean Myles, an agricultural scientist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and colleagues compared hundreds of pot plants and their breeds and found major inconsistencies, according to the paper.

The study found that in about one-third of the cases where they had two producers offering plants with the same strain name, the samples weren’t genetically identical.

The problem arises because the marijuana business doesn’t have industry-wide codes or ways of enforcing them.

And more and more consumers want to know what’s in their pot.

So producers and vendors are attaching more importance to “cannabinoid profiles,” which state which cannabinoids are present and in what quantities, than to strain names.

But what should go into a cannabinoid profile? For openers, they should tell you how much THC and CBD is in the product. Most strains sold in Colorado have that much on the label, and if they don’t, vendors will tell you if you ask.

But there are dozens of psychoactive cannabinoids in marijuana, whose presence or absence can make a difference in the medicinal and recreational properties of a plant. Only a few of these are even tested for.

Ditto for terpenes — aromatic oils that modulate the effects of cannabinoids, give various marijuana strains their distinctive odors, and play a role in defining the differences between sativas and indicas.

There are more than 100 terpenes in pot, and many of them are also produced by other plants, which is why marijuana strains with “blueberry” in their names smell like blueberries, for example. These are rarely listed, tested for or mentioned on the labels.

As a consumer, I’d like to know the THC and CBD content of the marijuana I’m buying, as well as the content of any other cannabinoids that are present in less than trace amounts, especially if they have subtle psychoactive effects. I would also like to know what terpenes are present and in what amounts, also especially if they have psychoactive effects.

Most important, I would like to see the industry agree on the cannabinoid/terpene profile that characterizes a particular strain. That way I could have some confidence in what I’m getting when I buy a particular strain.

And, again as a consumer, I would be very disappointed if strain names were abandoned. I want to be able to buy pot by name, but I want the names to mean something. And I don’t want to be buying pot that’s using aliases — like privateers sailing under false flags — or named pot that varies from batch to batch.

Today’s marijuana industry is largely made up of boutique producers and vendors, and most of us like it that way. But the industry worries about whether it will be displaced by “Big Marijuana,” which would be based on the business model of “Big Tobacco.” (Pot prohibitionists also routinely raise the specter of this happening.)

Just guessing here, but if it were to happen, it would be because consumers would be looking for the sort of product consistency and quality assurance that a big company can provide — often by dumbing down their products. The way to prevent this from happening is for the industry to get together and form a trade association that can certify what’s in various strains with some precision. Producers and vendors can then label their products as meeting those standards.

This need not be done on a national level to be successful. If the main players in the Colorado industry were to do it (or in any other state that has legalized) it wouldn’t be surprising if other states adopted the system.