In case you haven’t noticed, there’s been an increasing under-current of anti-marijuana legalization propaganda oozing into the mainstream media lately.

It’s probably a coordinated campaign, with some of the usual suspects involved, guys like Kevin Sabet of Smart Approaches to Marijuana, Former Drug Czar William Bennett, and some kind-of libertarian Fox News types like Tucker Carlson who ought to know better.

But there’s a new face as well: Alex Berenson, a former New York Times investigative reporter. Berenson has knocked out a book titled Tell Your Children: The Truth about Marijuana, Mental Illness and Violence.

According to Simon & Schuster’s promo blurb for the book, the gist of Berenson’s argument is that there is a “link between teenage marijuana use and mental illness, and a hidden epidemic of violence caused by the drug.

“Most of all, THC — the chemical in marijuana responsible for the drug’s high — can cause psychotic episodes. … Psychosis brings violence, and cannabis-linked violence is spreading.

“With the U.S. already gripped by one drug epidemic, this book will make readers reconsider if marijuana use is worth the risk.”

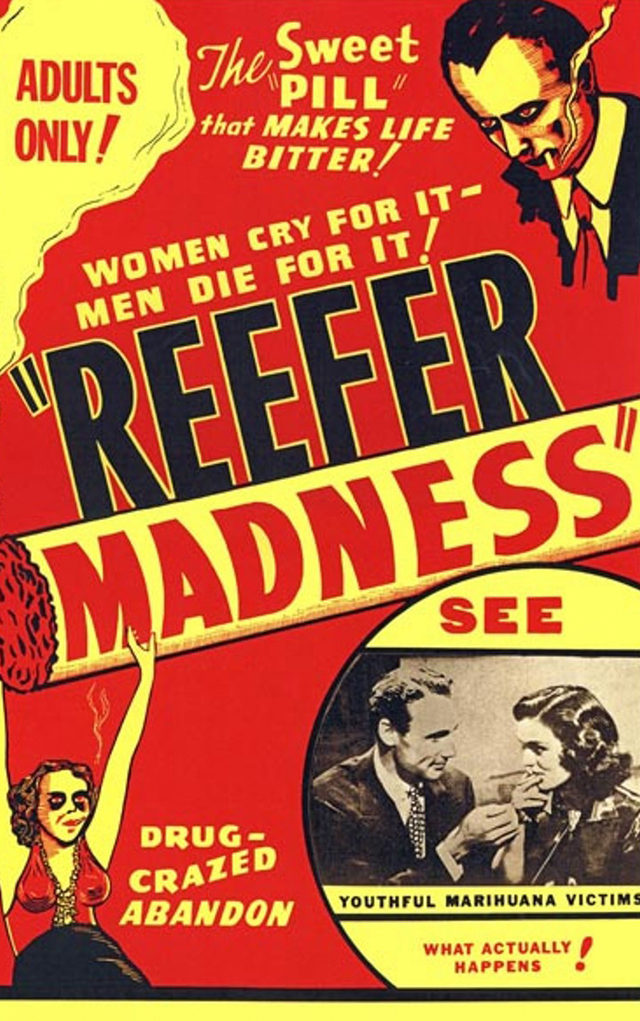

The book has received a lot of media attention, but as German Lopez concludes in a long, critical review on Vox, “it’s essentially Reefer Madness 2.0.”

Lopez says that while the book is “a compelling read written by an experienced journalist, it is essentially an exercise in cherry-picking data and presenting correlation as causation. Observation and anecdotes, not rigorous scientific analysis, are at the core of the book’s claim that legal marijuana will cause — and, in fact, is causing — a huge rise in psychosis and violence in America.

“The book largely focuses on grisly anecdotes of violent crimes committed under the influence of marijuana, the kind of ‘reefer madness’ stories authorities and the media leaned on when they first prohibited cannabis in the 20th century,” Lopez writes, citing Berenson’s claim that legal pot is already leading to a “black tide of psychosis” and a “red tide of violence.”

Lopez isn’t the only one to call out Berenson’s latter-day Reefer Madness. Last week a group of 75 academics and clinicians released an open letter blasting his methodology and rhetoric.

“In one of his book’s most disturbing passages,” the letter says, “Berenson suggests that one of the reasons that police so disproportionately arrest black people (nearly four times as often as whites) for marijuana use is that marijuana makes young black people mentally ill and violent.

“He writes: ‘Yes, marijuana arrests disproptionately fall on minorities, especially the black community. But marijuana harms also disproportionately fall on the black community… Given marijuana’s connection with mental illness and violence, it is reasonable to wonder whether the drug is partly responsible for those differentials.’”

The letter adds that, “Conveniently, Berenson ignores the fact that black and white people use marijuana at the same rates, and that the reason for the higher rate of arrests is over-policing of communities of color, based on prohibition…” and that Berenson’s allegation regarding black mental illness “reeks of the crack baby and super-predator myths of the ’90s…”

It also reeks of the 1930s racist claims by William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers, like that “marijuana-crazed negroes” were raping white women.

The letter makes two other points about Berenson’s book that should be obvious but apparently aren’t.

First, Berenson “ignores most of the harms of prohibition,” focusing mostly on the harms of marijuana use.

“None would argue that marijuana use is risk-free,” the letter said. “However, weighed against the harms of prohibition, including the criminalization of millions of people, overwhelmingly black and brown, and the devastating collateral consequences of criminal justice system involvement, legalization is the less harmful approach.”

Second, “the vast majority of people who use marijuana do not develop psychosis or schizophrenia, nor do they engage in violence…”

The last point lies at the heart of the argument against alcohol prohibition as well as pot prohibition.

Although an enormous amount of violent behavior is tied to alcohol abuse, the vast majority of alcohol users don’t become addicts, go nuts, or become violent, or even drive impaired.

In other words, the conduct of a minority of users is used as grounds to criminalize the behavior of the majority. That was the basis of alcohol prohibition in 1917 and marijuana prohibition in 1937. And now pot prohibitionists are trying it one more time.