When Victor Galván’s parents brought him over to the United States from Mexico, he was just 8 months old.

His parents are undocumented immigrants who hailed from Chihuahua, Mexico, but Galván, who speaks perfect English, grew up in the United States. In practically every sense, he’s American.

Except, of course, for the fact that like his parents, he’s an undocumented resident, and he has spent most of his life watching his back, knowing that one wrong move could get him deported.

He recounts one of the biggest scares he’s ever had, when, were it not for the discretion of a police officer, his future was suddenly up in the air.

He was driving his wife, Ana Cristina Temu, a natural-born citizen, to work and was in slow traffic on the highway. With little warning, a car smashed into his rear fender, and they had to pull over. As a non-citizen, he couldn’t legally obtain a driver’s license, and he started to sweat. He was looking down the barrel of deportation. If the cop so chose, he could have run Galván’s name through the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement database and arrested him on the spot.

“I’m thinking, the police are going to show up, they’re going to ask me about my status, my license, why I don’t have a license, and fear sets in that I might have to prove my legal status,” Galván recalls. “They’d deport me. That just runs through my mind.

Fortunately, he just gives me a driving without a license ticket, but for so many people that’s not the case.”

He got lucky. But it was a close call.

His brother wasn’t so fortunate; he was deported a year-and-a-half ago, even though he was just two years older than Victor when he came to the United States. He now has to find a life in Mexico, a country as foreign to him as it is to most other people living in the United States.

“He tells us how hard it is to live there,” Galván says. “It’s a constant struggle to keep work. The workforce is so competitive. Everyone is looking for work and it’s not sustainable.”

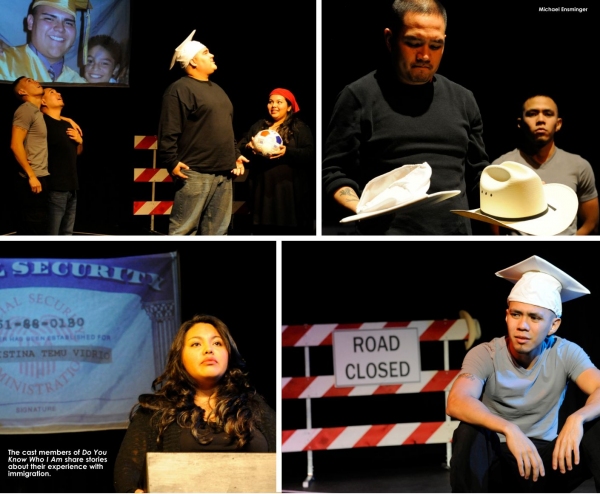

Galván’s story is a key part of Do You Know Who I Am, a theater performance organized by Kirsten Wilson of Motus Theater. The play stars Temu, Galván, and brothers Juan, Oscar and Hugo Juarez. Besides Temu, all are undocumented immigrants who came over at a young age. During the play, they all tell their stories of overcoming obstacles on their paths to becoming contributing members of society.

The goal, Wilson says, is to start a conversation in the community that will eventually impact the push for immigration reform.

The way the system is now, Wilson says, “We end up with these young people who consider themselves American. … They’re a part of our school system, they’re a part of our community, and yet they run into huge obstacles graduating from high school where they can’t get a driver’s license legally, they can’t hold a job legally, and yet they don’t know their country in which they were born, most of them have never even visited that place because they couldn’t legally get back. So they’re in a kind of purgatory that takes away their hope and their initiative. Some of these young people are huge assets to their community, and we insist on looking at them as problems.”

The show came about after the board of Motus Theater decided the organization should focus on immigration issues. Wilson reached out to Boulder County Legal Services to try to find immigrants willing to share their stories, and she was directed towards an organization called Longmont Youth for Equality. There, she met the students who would become actors in the play. After they shared their stories, the idea for the play came naturally.

“We helped them write their own stories, autobiographical monologues, and they were very, very powerful, and we thought it would be a great performance to really move conversation,” Wilson says. “So we upped the theatrical power by weaving them into a unified drama, and adding live music and photographs and really making it into a dramatic experience of what these young people’s lives are like as undocumented members of our community.”

The play starts out with Temu telling the story of getting rear-ended with her husband, Galván, and the fear the pair felt as the car hurdled towards them, when there was nothing they could do to prevent it. The stage is made to look like a street, and the story becomes a metaphor for overcoming obstacles.

“The whole thing is about how [the students] move forward,” Wilson says. “There’s no going back. There’s obstacle after obstacle put in front of these young people.

They’re moving forward with their education and their lives. This whole thing is coming at them, this legislation against undocumented immigrants, and there’s nothing they can do about it.”

Galván received a scholarship award from the city of Denver for overcoming adversity before it was yanked away after it was discovered he was undocumented. He is now part of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, a program created by a decree from President Barack Obama in 2012 after Congress failed to pass meaningful immigration reform. Basically, he gives his name, address and other personal information to the federal government in exchange for a “deferred deportation” that lasts two years. At the end of the two-year period, he will be eligible to renew for another two years. But if a Republican wins the White House in 2016, there’s no telling what the future could hold for Galván and the roughly 600,000 people who have applied for the program.

“They gave me a two-year work permit, and hopefully we’ll be able to renew it in two years,” Galván says. “But [the long-term future is] up in the air. … That’s why for me it’s so important that we pass another immigration reform bill.

“Temporarily, it’s really great relief knowing that we’re safe from the streets and that we’re able to provide for our families,” Galván says.

Respond: [email protected]