Golden Era Hollywood screenwriter Frank S. Nugent once described story as a disturbance of the status quo: “Something happens to upset it; the disturbance is the story; and the story ends when another status quo is attained.”

The Boy and the Heron from master filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki is Nugent’s aphorism writ large. Here is a story that opens by plunging the viewer into a world of exuberant energy, astounding artistry and jaw-dropping creativity, only to pause briefly two hours later before the protagonist exits the frame and the credits roll. In between are worlds few could conceive of, and fewer still could visualize.

Much has been written of Miyazaki’s on-again, off-again retirement. By some counts, he has either retired or threatened to retire eight times. None of them have stuck. Lucky us. And though elements of The Boy and the Heron — the 82-year-old filmmaker’s alleged final film — feel like familiar territory, there are still moments, like the movie’s opening, that find the dedicated hand-drawn animator discovering new ways to express emotional truths.

That opening, set three years into World War II, finds the boy, Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki in the Japanese version; Christian Bale in the English dub), losing his mother in a hospital fire. The scene plays like an impressionistic nightmare full of wispy lines, smoky figures and fluid bodies. Is this the emotional experience of Mahito in the moment or how the memory haunts him years later? No time for that now: Mahito’s father just remarried — his sister-in-law — and they have a baby on the way. So Mahito is scooped out of Tokyo and sent to the country to live with his new mother at Gray Heron Mansion.

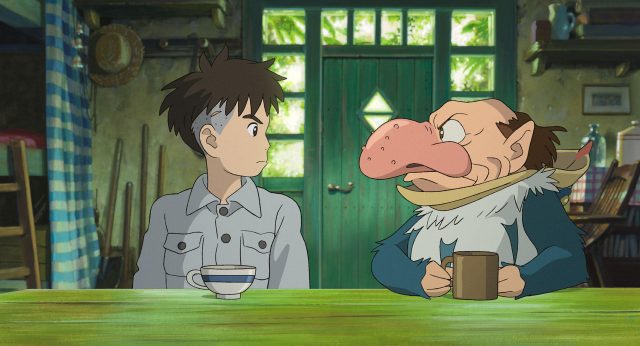

The mansion’s caretakers, comical and grotesque characters that look like they wandered out of a — well — Miyazaki movie, provide comic relief before revealing themselves to be much more. Nearby is an ancient tower that is easy to see but hard to get to. Mahito wants to know what secrets it holds. He also would like to know why that heron keeps pestering him.

Miyazaki and his team are setting the table for the wonders to come: an array of dream worlds and alternate realities populated by baffling creations, adorable spirits, militant parakeets, headstrong women, earnest girls and an eternal spirit ready to die. It’s as enchanting as it is haunting.

But how is this happening? One explanation is that Mahito, who is being bullied at school, takes a rock and hits himself on the head so he won’t have to go back to class. But the damage rendered is more severe than Mahito intended. Could this trip into another world where he meets his mother as a young girl be the result of his self-induced trauma? Maybe. But what about that heron? Even before Mahito whacked himself upside the head, Miyazaki offers us a glimpse of the heron grinning with giant oversized human teeth. And how many herons do you know that have human teeth?

There’s a lot of talk these days about how artificial intelligence will shape our world, particularly when it comes to entertainment. Its effect will be significant, no doubt, and I’m sure AI programs will be trained to parrot Miyazaki’s movies. Even then, I doubt the technology will ever be able to invent a world as colorful, vibrant, lived-in, imaginative and grounded as this. If The Boy and the Heron is truly Miyazaki’s last, then the final seconds of this movie are a simple and satisfying conclusion to a lifetime of work. If it isn’t, then I can’t wait to see what comes next.

ON SCREEN: The Boy and the Heron opens in theaters Dec. 8.