If we’re to trust Thurston Moore, “Rock stars can’t be poets, which sucks.”

The line is from a poem by Moore titled “By The Lightswitch.” It’s not actually a comment on whether musicians can cross into poetry, but whether Moore can escape his own very public identity.

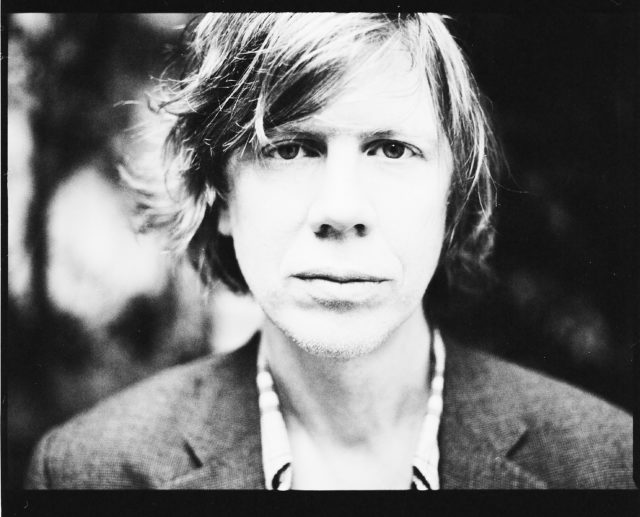

“You’re always going to be perceived as what you’ve established yourself as through the years, and [for me] that’s as a musician,” Moore explains during a Skype call from his home in London.

“When I’m at a reading, sometimes I’m attracting attention because I was in a kind-of-high-profile indie rock band,” Moore says through my laughter. “There’s always going to be that patina, and I have this desire to be known exclusively for what I’m doing in that moment with poetry. And I know that just can’t be the case unless I get some plastic surgery and change my name.”

While Moore is best known as co-founder of the “kind-of-high-profile indie rock band” Sonic Youth (a band David Bowie once said was “so important to the ’80s”), he’s been a serious poetry archivist and practitioner since the late 1980s. Indeed, it’s been said that poetry, not music, was the magnet that pulled an 18-year-old Moore to New York’s Lower East Side in 1976. But, as with most stories, Moore says the truth lies somewhere in between.

“I think deep down I really just wanted to run off and play electric guitar with a rock ‘n’ roll band,” he admits. “But in a way you couldn’t tell your parents that was a serious endeavor, but if you said you wanted to be a writer or a journalist, that was taken with a little more validity, there was value to that ambition.”

Moore did write poetry — “a lot of kind of simple poetry,” he says — living in his $110-a-month apartment in the East Village, right in the heart of a percolating scene in New York that would shape music and pop culture for decades to come.

Journalist Will Hermes describes the era from 1973 through 1977 in great depth in his book Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years In New York That Changed Music Forever.

“Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataaa and Grandmaster Flash hot-wired street parties with collaged shards of vinyl LPs,” he writes. “The New York Dolls stripped rock ‘n’ roll to its frame and wrapped it in gender-fuck drag, taking a cue from Warhol’s transvestite glamour queens. Bruce Springsteen and Patti Smith, both bussed in from Jersey, took a cue from the elusive Dylan, combining rock and poetry into new shapes.”

(Digression: It’s all too easy to forget — or be unaware — of Springsteen’s punk proclivity, but pick up a copy of The Boss’s 2014 album High Hopes to hear a cover of “Dream Baby Dream” by electro-punk pioneers Suicide.)

Moore was there while this pioneering, poetic punk rock grew in the dark clubs of New York City, in 8BC, 82 Club, Max’s Kansas City and CBGBs. He grew fascinated with musicians who referenced poetry explicitly in their music — Patti Smith, of course, Lou Reed, David Bowie, Richard Hell and Tom Verlaine — and he credits them with helping to “elucidate this reality of being both a writer and a musician and having them have equal stature.”

Still, in the early ’80s, Moore was engrossed with the music he was creating with Sonic Youth.

“All my writing was all in the service of the music, and I would transmute poems into music so they would have rhyming schemes because rhyming works so well with music as its friend but sometimes it can be a little cornball just as a poem on the page,” Moore says.

“I didn’t think I needed to be published or work with the poetry world, because I was ensconced with Sonic Youth and that was full time,” he adds. “My interest in poetry came to a real head in the late ’80s and into the ’90s. I sort of became aware of the publishing history of underground poetry, and it fascinated me the same way that underground music fascinated me with the obscure LPs and 7-inches and such. I really liked these kind of artist-made documents. I always found them to be really vital to culture. So when I got a sense of what underground publishing had been going on since the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s in New York City, [it lead] me into [poetry from] other regions, the Midwest and the West Coast and Canada, Europe and England. It just became explosive for me, and so for years I did research and I would get leads.”

Perhaps one of the most significant leads came from punk rock innovator Richard Hell (of the Voidoids). He suggested Moore go see Steve Clay.

Clay was, and still is, director of an independent small press called Granary Books. In Clay’s collections, Moore discovered books that belonged to Francis Waldman, sold to Clay by Anne Waldman, co-founder of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University. Moore studied the works he found and began to attend poetry readings in New York, something he wishes he had been attending “since day one.”

“I so regret not going to so many poetry readings in the ’70s and ’80s when I was around New York because they were all just down the street from me,” he laments. “But I was doing some other things that were pretty good, just seeing bands and whatever was happening in whatever providential existence I had, but I do regret not taking part in the Poetry Project scene in New York City at a really critical time in the ’70s and ’80s. But so be it.”

Moore eventually got to know Anne Waldman, and in time she invited him to participate in readings, including some at the famed Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church. She also asked him to teach at Naropa’s Summer Writing Program.

“You know, I could never do it,” Moore says. “It took me forever to say yes to that. When I did, five years ago, it was a big shift for me in my life. It introduced me to a world I felt at home with. The poetry world around Naropa has interconnectivity with Buddhist principles. I’m not a practicing Buddhist — hardly a scholar — but the simple tenants of Buddhism give me a lot of solace. I find them intellectually stimulating. I really respond to it. That connection I find really profound, so I love returning there — it regenerates me.”

He’s returned to teach at Naropa every summer since 2011.

Moore operates two publishing companies, a boutique publishing house called Ecstatic Peace Library, and a poetry-focused small press called Flowers & Cream.

It was only last year when Moore released a large and rather intimate collection of his own poems and lyrics in print for the first time, a work called Stereo Sanctity Lyrics and Poems. The book contains more than 30 years of Moore’s lyrics from his time with Sonic Youth and as a solo artist, as well as poetry reflecting on life, politics and, of course, punk rock.

The idea for the collection stemmed from one of the summer writing workshops Moore leads each year. He’d written an essay about the distinction between lyric writing and poetry and how the two coexist. From there, Stereo Sanctity came to life.

Much ink has been spilled examining the connection between poetry and rock ‘n’ roll. Some of that ink came from the pen (proverbial as it may be these days) of Stephen Burt, a literary critic, poet and professor at Harvard University.

“Rock is easy, poetry hard to create,” Burt writes in an essay titled “‘O, Secret Stars, Stay Secret!’: Rock and Roll in Contemporary Poetry.”

“Rock is spontaneous and simple; poetry intricate, enduring, reflective. Rock is ephemeral, while poetry endures. And rock songs (for all those reasons) belong to the young, as poetry maybe did once but sure doesn’t now — or so we assume.”

Here, Burt teases apart the notion that many poets covet the trappings of rockstardom — the fame, the immediacy, the undeniable cool.

And yet Moore is among those rock stars drawn to the difficult, enduring nature of poetry, with all its intimacy and intellectual prestige. He knows many have tried to cross the great chasm between musician and poet with nauseating results. But it seems that Moore was never just a musician or just a poet; he was always both. There was no chasm to cross.