Travis LaBerge’s family didn’t have a lot growing up, but there was always music in the house. Despite living between paychecks, his parents socked away enough to provide him with a piano instructor who charged on a sliding scale. Now the executive director of the Boulder-based Parlando School of Musical Arts, LaBerge is paying that gift forward to students here on the Front Range.

“I didn’t tell this story growing up because I was so embarrassed about it. But I’m happy to tell it now, because I feel like it shows the importance of supporting kids who have passions,” he says. “As I became an adult and was thinking about what to do with my life, I knew I wanted to be part of a larger movement that allowed kids to have the same opportunity I had.”

Parlando is an Italian word meaning to speak, and central to the mission of the nonprofit founded by LaBerge and his wife Christine in 2003 is a drive to help young people find their voice through music. Billing itself as Colorado’s largest stand-alone arts outreach and education provider, the 501(c)(3) headquartered at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder offers private lessons, group classes and workshops “for all instruments, ages and abilities.”

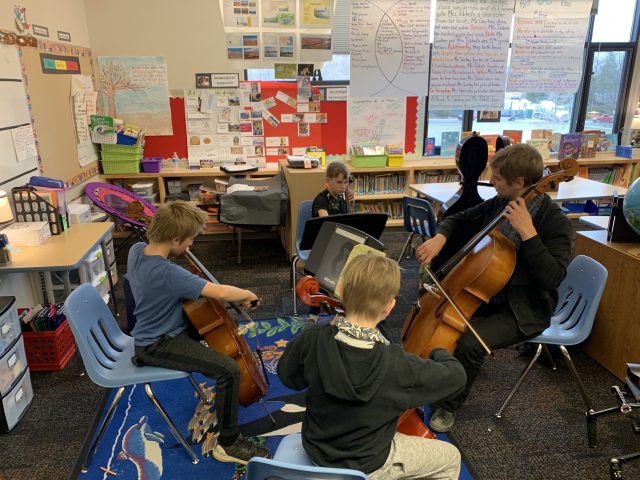

In addition to raising up to $75,000 annually for tuition assistance, Parlando also implements an outreach initiative to help local public schools supplement existing music education programs that are often the first on the chopping block during budget downturns. The idea behind the outreach effort dubbed MORE for Colorado, designed to focus on Title 1 and low-income schools, is to dispatch Parlando music instructors during regular hours to keep young musicians engaged in their existing programs while easing the burden on teachers who say they don’t have enough time or resources for their students.

“It’s been a really critical way to reach kids who might have slipped through the cracks if they hadn’t gotten that one-on-one and small-group support,” says Casey Middle School music teacher Kati Sainz, who once worked as a Parlando instructor while earning a graduate degree at CU Boulder in the early 2000s.

Now Sainz and her students at Casey, distinguished as a Colorado School of Excellence in Arts Education, are on the receiving end of a program that has supported 3,000 classes in 29 schools across the region’s four major districts this past academic year alone. The longtime educator says it all comes back to the fundamental value of music instruction for young people.

“I have seen kids who might have been really school avoidant come around and find their place in a music program, which they might not have found otherwise,” she says. “They find their crew, which is so important for middle-school kids: a group they feel comfortable with, having fun going on field trips and making music together as a regular part of their school day. It’s really critical that we include it as part of the curriculum, and give kids from all socioeconomic backgrounds and abilities the opportunity to thrive.”

‘No one wants to play a broken instrument’

But however effective a supplemental in-school program might be at reaching students and alleviating the pressure on overworked educators, it doesn’t amount to much if the instruments aren’t in good shape. That’s the message a Parlando instructor brought back to LaBerge in February of this year.

“He said, ‘Travis, what we’re doing at this school is great, but my students’ instruments don’t work right. I’m spending more time in my sectionals trying to do basic repairs — some of which I can do, some of which I can’t,’” the executive director recalls.

So LaBerge contacted local partner schools to determine the severity of the problem. After learning how widespread the issue was, Parlando partnered with Flesher Hinton Music in Wheat Ridge to collect and repair 83 different instruments from nearly half a dozen local schools over spring break. That included Casey, where Sainz says many students participating in the free-and-reduced lunch program can’t afford to pay the yearly rental fees typically charged by schools to help with upkeep.

“We tend to have a ton of instruments and it’s very difficult to keep them in good repair — and no one wants to play a broken instrument,” Sainz says. “So when Parlando stepped up to help out with some of those repairs, the kids had instruments that were working correctly and more fun to play. Which was so helpful, because it’s very difficult to encourage kids to practice if their instruments aren’t working.”

LaBerge says the point of initiatives like this year’s instrument repair project — and the Parlando vision writ large — isn’t to train the next generation of concert violinists and pianists, necessarily. He says it’s about facilitating a deep and abiding sense of joy while fostering the life skills that come with learning to play, whether music is one of a student’s laundry list of weekly activities or the golden ring that will steer the course of the rest of their lives.

“Most of the students we work with fit in between those two extremes. We’re simply interested in them learning how to play their instrument: enjoying that process, finding joy in it, and hopefully music will be a lifelong skill they take with them,” LaBerge says. “If we invest in these kids now, [think about] what they will be able to achieve, and what they will be able to give back in the future. It obviously becomes something much bigger than any one person, or any one teacher, or any one organization. It’s how we make the world a better place.”