They conduct themselves like madmen, and explain their behavior by saying that in their thoughts they soar in the most far-off worlds … Every day is for them a holiday. When they pray .. they raise such a din that the walls quake … And they turn over like wheels, with the head below and the legs above

— From a denunciation of the Hasidim by traditional Eastern Europe Rabbinic authorities, circa 1772

As long as music has existed it has bridged this gap between heaven and earth, from the earliest evidence of prehistoric music, shamanic in its imitation of natural sounds, to the marching of Gregorian chants aimed straight at God himself, to the holiday songs ringing in the season of giving.

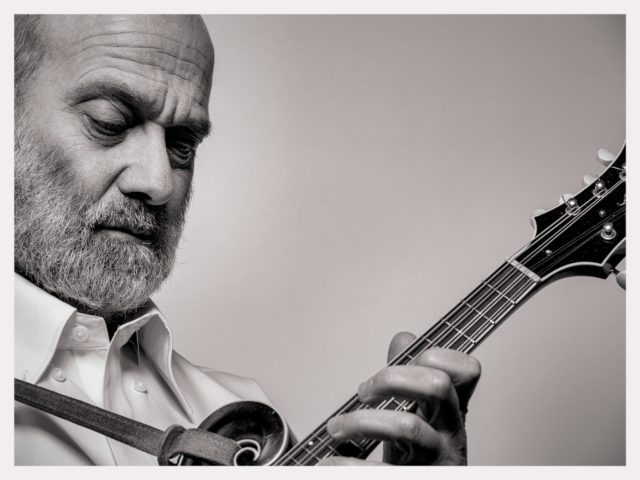

No matter how the holidays might have become estranged from the spirit of the season, the connection between music and the divine persists. There is perhaps no better testament to this than Andy Statman, New York-based maestro of clarinet and mandolin, who played with his trio at Boulder’s newly built Jewish Community Center (JCC) in November.

The trio opened its set with a 25-year-old Hasidic melody, written to induce a spiritual experience in both the player and listener. Despite its recent composition, the song sounded ancient, like it could have been written more than a century ago as a more traditional Klezmer tune.

Until Statman, Klezmer music was not used to refer to a musical style, merely applying to a loose genre of Jewish instrumental folk music stemming from the tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe.

In 1995, Statman released Songs of Our Fathers with David Grisman, a collection of Jewish songs, most of which are more than 100 years old, heralding a regeneration of the culture’s music. The album was Statman’s communiqué about his own religious journey, and it struck a chord with an entire generation of American Jews, of which the audience at the JCC, mainly Jewish, mostly liberal and almost entirely of the baby boomer generation, represents well.

Kathryn Bernheimer, cultural arts director for Boulder’s JCC, says her generation was accustomed to music acting powerfully as a vehicle for emotion, passion and human connection. Many of the Jewish children of the ’60s and ’70s, having rebelled against the religion of their parents, found a surrogate community in rock ‘n’ roll. But when she heard Songs of Our Fathers, Bernheimer says she rediscovered her long latent heritage and recognized a crucial part of her identity as a Jew.

Statman, too, found his religion later in life. As a Ba’al teshuvah’, a Jew who returned to orthodox Judaism later in life, Statman famously says that it was through music that he found faith. To watch his audience at the JCC listen to his music was to witness a similar phenomenon.

At first the room sat still and quiet, likely struck with a sense of awe. Haloed in dim light on the stage, Statman appeared divine, larger and somehow separate from life.

But it was only a matter of minutes before the trance broke and the audience was moved, not necessarily to find God or religion, but to a more personal experience, as tears welled from their eyes and people spontaneously jumped from their chairs to dance.

“[This feeling] is somewhat describable, but it’s something that really rings true to you when you experience it,” Statman says in an interview with Boulder Weekly. “You know it’s true, but you might not be able to say exactly why. It is an encounter with the truth.

“[These experiences] are not an end in themselves, they are a sort of gift and they are necessary because they can confirm your faith and your belief system.”

To hear him explain it is to hear a phenomenology of religion in the Hasidic tradition. Here, where the ideal is to live a hallowed life, even the most mundane action is sanctified as a worldly experience of God. In Hasidism, practitioners actively seek such experiences and, overtime, music has emerged as one of the most effective ways of connecting with God.

This is the power of music, a universal language that compels us to experience something outside of the everyday events of our lives. But Statman’s music is remarkable in that it incorporates both the commonplace and the otherworldly.

“In all Judaism, as a religion, everything is supposed to happen here,” Statman says. “You have jobs to do here in the world. As spiritually high as [Judaism] is, it is equally mundane.”

Statman’s love for music grew from rock ‘n’ roll and bluegrass, genres he still loves today. Aside from studying with distinguished traditional Jewish musicians like Dave Tarras and Itzhak Perlman, Statman played with bluegrass greats like David Grisman and Bela Fleck.

Now 66 years old, Statman is no longer a student but a master artist in his own right. With more than 30 albums, several Grammy nominations and a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Statman is inarguably accomplished.

And yet he’s one of us. Five songs into his set at the JCC, Statman stopped to talk with the audience about the Broncos game earlier that day before he and his trio, with Jim Whitney on bass and Larry Eagle on drums and percussion, broke into more than an hour of secular and sometimes even Christian-inspired bluegrass songs.

Through these transitions, the specifics of the Jewish faith gave way to universal beliefs, and it became clear that transcendent experience does not exist solely in sacred songs played by a master, but in songs simply played with devotion.

“Everyone has faith in something, you know,” Statman says. “They might have faith in themselves, or in politics, or a particular candidate or ideology. Everyone has faith. That is a universal given, you know. Even if it is faith that the sun will come up and that there will be day or night.”

Music, he says, is an art form that embodies the joy, tragedy and banality of living. To simply live from moment to moment requires us to proceed with a certain sense of faith.

In the midst of the trio’s rendition of “Shenandoah Valley Breakdown,” a jolly bluegrass classic, Statman suddenly pulled his mandolin from the mix and began to retune the strings. Moments later he returned, his mandolin now sharp and out of tune, and entered into a discordant jam with the unchanging bass.

“I did it because that’s where I wanted to go,” Statman says. “Because that’s what I felt like doing in that moment. In other words, when I play it is a lot like a conversation, a focused conversation that exists totally in the moment.

“We really have no real arrangement and no real set-lists, only the most general of outlines. We are open to what is going to happen. We all know the music, we all know the melody, we all understand the feelings that are being produced by a particular melody and we have fidelity to that.”

For one night in November, the JCC was truly a modern version of shul, a Yiddish word meaning school, rooted in the Latin word for leisure. Onstage, Statman was utterly unconcerned with productivity, profit or politics but simply a focused conversation, a moment in life in service to something bigger. Therein he made room for spontaneous experiences, for both the player and the listener.

As the holidays press nearer and we congregate with our friends, families and communities to celebrate the spirit of the season, days will undoubtedly be full of the mundane, of feasting and cleaning dishes, or navigating family dramas and buying last minute gifts. But they are also full of occasions for the divine, for experiences of emotion, love and joy, and maybe Statman can be a reminder to heed that call in the music of the season.

“The reason that people are drawn to music, by and large, is because they enjoy it,” Statman says. “Music is fun; it induces an experience that people like. I think that the basic reason why people listen to music or play it is because it is fun and only then can it become a gateway for other things, like faith, as well.”