I was dreaming of Costa Rica. Of long nights drinking guaro and mangling Spanish grammar; of sea turtle-laden beaches stretching into the horizon, iridescent with moonlight.

But that paradise suddenly vanished with the nasal whine of a two-stroke alarm clock that hit like an aneurysm.

An orange-vested maintenance man was piloting a leaf-blower outside my apartment window, just an arms-reach from my bed. Drugged with sleep, my head splitting in two, my snap emotional reaction was to start stabbing, or at least yelling in protest. But my clock said 7 a.m., meaning it was too late to do a damned thing about it.

His noise was on the clock.

• • • •

I was 18 the first time I was issued a noise complaint by the police. It was 1:30 p.m. on a Saturday and my first rock band was working on a new song inside a bedroom we had soundproofed with so many layers of carpet, foam and mattresses on the walls that the space doubled as our house wrestling ring.

Though this new song was only marginally less mediocre than our other songs, it still felt like unfiltered magic, and we were sure the world would soon be beating down our door to hear it.

But it wasn’t the world that came to our door. It was the police, who had been called by the couple who had moved into the house across the street the year previous to run a bed and breakfast.

They were not fans. The feeling was mutual.

For rocking a little too hard, the judge at civic court ruled that I must pay a $250 fine and be fingerprinted for the FBI database. Further violations could result in a city-forced eviction from the house I rented from my parents and potential jailtime. The criteria he used for this and future violations was that the noise was “unnecessary.”

One of the few effective outlets I’d found for the emotional volatility of being a teenager was playing the drums. Primal screams of indiscriminate rage became crash cymbals. Turbo-charged giggle-fits became double-time, four-on-the-floor beats and eighth-note rolls. Sobs became a softly-brushed ride. I was closer to Ringo Starr than Buddy Rich skillwise, but it kept me together when it felt like I was falling apart in a way nothing else could. But according to Judge Drescher, none of that was “necessary.”

I could hear the roar of a car-sized riding lawnmower outside as he struck his gavel.

• • • •

As a musician, my life is a philosophical war over noise; where, when and how it is acceptable and legal. It has shaped where I live and work, and what sort of music I play and listen to, and even whether I can pay my rent.

The first element of the conflict stems from the paradigm that silence is the world’s default setting and that noise is a deviation. If you take a strict scientific view that sound only occurs when previously at-rest air is set to vibrating, then sure, that’s the way it is. But we don’t live in a vacuum, and the meaning of the facts changes with existential context.

The average conversation is between 60-70 decibels. The constant chatter of sylvan wildlife is about the same, though far louder in more densely populated tropical jungles. Ocean waves stretch upwards of 80 decibels. Niagara Falls roars at 95. Barking dogs can reach 115. Thunder routinely hits 120, near the point where sound can hurt. Blue whales sing at 188 decibels, and can be heard for hundreds of miles. Earthquakes can reach 235 decibels. Then there are volcanoes. The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia was so loud it was heard nearly 2,000 miles away in Perth, Australia.

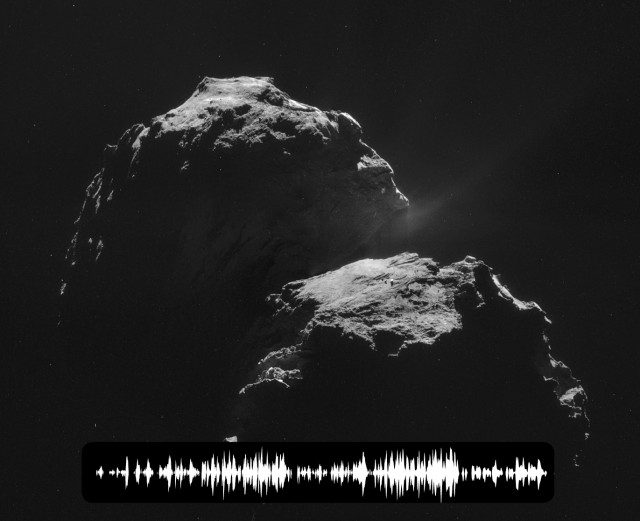

This noise is not just an earthly phenomenon. When scientists recently landed the Rosetta probe on Comet 67P, they discovered that the comet “sings” by ionizing particles that it sheds into space.

Even in space, where there is no sound, nature is loud.

And that is to say nothing of civilization.

A blender is 80 decibels, and a home dishwasher pushes closer to 90. Fifty feet from the freeway, a single passing car is still 80 decibels. Motorcycles average 100 decibels. Rush hour can create sustained levels closer to 120.

Decibels are measured logarithmically, which means that an increase of 10 is a doubling of volume. So these are not small leaps. Nor is it a small leap that from 100 feet away, a jet engine is measured at 140 decibels, or that fireworks can reach 150 decibels.

It is also not a small distinction that the sound of the lumber mill 500 feet down the street from where I was ticketed for playing music is 118 decibels, about 10 decibels louder than the average rock concert.

Even just the ambient sound of the power transformers on the average house can be measured at 50 decibels from 100 feet away.

Noise, not silence, is the norm.

That means that the conflict is really over what noise is perceived as legitimate, and what noise is perceived as a nuisance. And when it is industrial noise that chews up and spits out pieces of the earth like a wood chipper, its legitimacy is never questioned. When it is cultural, a matter of free expression, noise is an issue of constant controversy.

• • • •

Boise, Idaho. Summer, 2013. I had been laid off from my job in March and turned to busking for rent in the nightlife district until I found a new job. Preferring to stand apart from the legions of acoustic guitar players doing the same, I armed myself with a ukulele and belted out a set of heavy metal parodies and country classics that did well at open mics. People gave generously when they could hear me, but it didn’t take long to discover that the thin sonic range of the instrument couldn’t cut through the din of thousands of drunks. Several hours of busking left my voice ragged and my hat empty.

After a week of lemon tea and financial anxiety, I tried a new strategy: plugging my synthesizer and a small amp into one of the open outlets in the urban plaza.

Within minutes I was scoring a dance party, with happy revelers dumping money into my case by the fistfull. One scooped up a wad of cash to “make it rain,” back into my case. The financial anxiety of unemployment began a slow retreat.

Until the police arrived with the message that unauthorized “amplified sound” is illegal.

“You need to go the store and get yourself an acoustic guitar,” one of the three cops told me.

There are so many things I wanted to say in response, like that the next time he needs to shoot someone, he should just point his finger and say, “Bang!” (since just like switching a synthesizer for an acoustic guitar, it’s the same thing), or that acoustic guitars are expensive and I’m busy trying to make rent money.

But none of it mattered. I was surrounded by three men with their hands on their guns and no interest in talking things out.

So I returned home to the dilapidated house I rented in an abandoned neighborhood that I deliberately picked so I could play the drums without issue, where my only neighbors were a boarded-up house full of feral cats, an AA drop-in center and a rock promoter who once had to do five days in jail for a noise violation.

I passed two fights outside bars on the way home. Not a cop in sight.

• • • •

It was not the first time I’d faced the police while busking, nor am I the only street performer who deals with this issue. In October, a video of New York City subway (average volume between 92-102 decibels) performer Andrew Kalleen being arrested went megaviral, garnering writeups in major news outlets like Time Magazine, The Guardian and Russia Today, as well as countless music blogs. Outrage wasn’t just that busking clearly didn’t rank on the most pressing issues facing the police that day in New York City, but that the busker cited the law showing his actions were legal and was arrested anyway. He will have to spend time and money fighting the issue in court, and will then probably be more hesitant to return to his completely legal activities, making it harder for him to earn a living and resulting in less music in the world. Even if the cop who arrested him is disciplined, there are countless others who will treat Kalleen and his peers similarly. What the law says is largely secondary to the fact that if the police want you to move on because they don’t like what you’re doing, then the issue won’t be dropped. If not noise violations, then police can say you’re loitering, harassing people or something else — things they would never say to a maintenance person with a leaf-blower, though street musicians are also just doing their job.

Nearly anyone who has performed on the street (often the most dependable way to make money as a musician) should be able to tell you some version of this story. Some towns ban open cases or hats, some require permits, others have limited zones in which musicians may perform. Sometimes those regulations have to do with ensuring that pathways are not blocked — which is totally reasonable — but with them generally comes regulations on noise (which almost all towns have independent of busking regulations as well) and those are where things get dicey.

Noise regulations tend to distinguish between “amplified” and “un-amplified sound,” and they tend to cap the limits on amplified sound — most commonly that it can be heard no more than 50 feet from its source — but apply no limits to unamplified sound. That’s why the police told me to get an acoustic guitar.

But according to that delineation, a hand-cranked air-raid siren is legal (audible for miles), as is a drumline (capable of being heard in a noisy football stadium), and opera singers whose voices can rival the volume of a jackhammer, and countless other things that can be heard more than 50 feet away. If the issue is volume, then noise ordinances regulating “amplified sound” are poorly tasked to address it.

The result is that noise enforcement is largely arbitrary, subject to the whims of those tasked with enforcement.

Some might say that the delineation has something to do with what music is soothing, and which is aggravating. Except that the listening experience is highly subjective. Most metalheads would rather be stabbed in the eyes than listen to The Carpenters, and vice-versa. And it implies that something being soothing is somehow objectively superior to being rattled, rather than just a different place on the emotional spectrum. But even if that were true, it still wouldn’t account for the fact that the volume of music is a subject of debate, but not the volume of a factory.

To that some might say that a factory creates jobs — is a valuable part of the economy. But that not only places a premium on money as the only measurement of value, but it also ignores the jobs that come with culture. A rock club creates jobs just like a factory, oftentimes even beyond its walls by serving as the cultural anchor that helps revive a depressed neighborhood. A lively business district full of buskers gives work to performers, while making the street more attractive to shoppers. The same can’t be said of a sidewalk cafe next to an airport or a factory or even a four-lane street. Noise from culture draws people in; noise from industry drives them away. But the former is highly regulated and the latter is not.

In addition to all those questions, there is a bigger problem: an inaccurate distinction. Amplification increases the volume of sound. The wooden box of an acoustic guitar is an amplifier, as is your voicebox, and countless other items that are lumped into the unamplified category of sound. Amplified, legally, means electric. And the subtext has less to do with volume and more to do with style.

Not just any musician but any designer will tell you: form leads content. No matter what you do, a single-coil Fender Stratocaster played through an amp loaded with spring reverb will sound like surf music, which will then lead the guitarist in that direction. A Les Paul played through a fully-cranked Marshall stack will always sound like rock, and lead all jazz guitarists back from Django Reinhardt’s catalog to that of Guns N’ Roses. The sound of a sitar will inevitably lead one to play East Asian music. Not all sounds are that hyper-specific, and sometimes sounds lead to new genres, but the point is that there is no way to make a tuba sound like heavy metal instead of weighty brass. And if you want to play something that cannot be done on an “unamplified” instrument, then you face legal restrictions that hamper that effort. America is a country founded by cultural outliers on the idea that fringe forms of expression should not be legally discriminated against. Yet that is exactly what noise codes do. Their limitations create a form of cultural hegemony that explains why walking the Pearl Street Mall recently in Boulder, a town that views itself as endlessly open and creative, I heard three different acoustic guitar versions of the same Beatles song, but no hip-hop, no EDM, no Kraftwerk, no black metal, no gospel organ and so on. I didn’t even hear a theremin version of “Blackbird.”

• • • •

Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is now recognized as one of the most important symphonies in history, an intensely emotive piece of avant-garde compositional wizardry. But when it premiered in 1913, the audience didn’t feel that way at all. They rioted, turning on each other, hurling things at the orchestra and trashing the theater. It has even been reported that members of the audience pummeled one another in time with the dissonant stabs that famously open the piece, which is almost comic to imagine. More than 40 people were ejected from the performance.

Neurologists examining how the brain reacts to sound would later conclude that new or unfamiliar sounds can be interpreted as a threat, and that the audience’s reaction was one of psychological selfdefense against a symphony far ahead of its time. However, once the ear acclimates to a new sound, the perceived threat would recede, which helps explain why The Rite of Spring was hailed as a masterpiece within a few years of its debut. It also helps explain why Bill Haley and the Comets’ now almost childishly innocent hit song “Rock Around the Clock” inspired riots across Europe in 1958, why white people panicked over rap in the ’80s and why so many small-metro TV stations have a report on the threat posed by punk rock somewhere in their archives.

The opposition to noise has nothing to do with volume and everything to do with cultural acceptance. That is why the music my band played was legally punishable, but when the same neighbors who called the police on band practice put a speaker on their front porch to play Muzak renditions of Christmas songs 24 hours a day, the police weren’t interested.

“It’s just Christmas music,” the officer told me after my revenge complaint.

But more importantly, that’s why when my band set up outside a different practice space to enjoy a sunny spring day, a man running a Skillsaw at a nearby construction site unironically stopped working to ask us to turn down. Though the noise of his labor literally sounded like a buzzsaw, no one questioned the legitimacy of building another ugly apartment building in another ugly subdivision. He was on the clock; we were just hopeful amateurs.

• • • •

Though I’ve always maintained a strict personal code of no drums after dark (except in winter, obviously), and try to keep my noise to hours in which it won’t cause others harm, I have lost track of how many times I’ve had to deal with the police over noise violations. At home, in the streets, at gigs. I’ve had to take down my equipment under armed watch and load it out through a fleet of police cars. There is always the threat of jail, eviction or just a giant ticket that could cripple me financially.

Considering that I’m just trying to go about my business, it’s frustrating. We are drowning in sound, but somehow musicians are accountable for it in a way others aren’t. And I’ll admit, I’ll take a world of leafy lawns over one with leafblowers, a world of quiet bikes over gasoline-powered cars and one in which the wood in my guitar was shaped by hand-tools over the roar of motorized blades. I have yet to encounter the pothole I wanted fixed badly enough to suffer the sound of a jackhammer, especially as an alarm clock. So perhaps I’m no different and I perceive my noise as legitimate primarily because it’s noise I like.

But other than the half-joking revenge complaint about my complaining neighbors, I have also never taken action against other’s sonic indiscretions, because I can see how the American ideal that your rights end at the tip of my nose doesn’t apply to noise. That would mean no one gets to make any noise for any reason because someone else might hear it, or that no one should ever have to hear something they didn’t expressly authorize, a nightmarish scenario in which there is almost no ability to accidentally encounter new ideas. For me to make the sounds I hold dear, I accept that others value other sounds, no matter how horrible they may be. To repurpose that old free speech trope: I may not agree with what Nickelback is doing to a defenseless guitar, but I’ll forever defend their right to do it. I’d even take to the streets, chanting and marching and playing an unamplified drum for the rights of that maintenance man who didn’t have the courtesy to wait until the sun came up to start blowing leaves around a parking lot instead of using a rake.

But should that march ever happen, I wouldn’t be surprised if its plea were drowned out by the din of a passing streetsweeper, its roar wiping the world blank once again.

Respond: [email protected]