Drew Emmitt and Vince Herman don’t exactly love the idea of being musical elder statesmen, but the fact remains that Leftover Salmon is the Rolling Stones of the jamgrass genre.

Nearly 37 years after the duo met in Boulder, their band still plays 100 headlining shows a year, and a who’s who of bands, from Greensky Bluegrass to the Infamous Stringdusters, acknowledge Leftover Salmon as their inspiration.

“Billy Strings told me once that he was my other son,” mandolinist and singer Emmitt says with a laugh. Strings, who recently sold-out multiple nights at Red Rocks, is bluegrass music’s reigning superstar.

Leftover Salmon will be inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame this year along with two Boulder-born ensembles it influenced, Yonder Mountain String Band and The String Cheese Incident—you can catch all three bands during a three-night run of String Cheese-headlining shows at Red Rocks July 15-17.

The party started on Oct. 29, 1985. “I moved to Colorado from West Virginia with a buddy. We pulled into Boulder and saw that ‘bluegrass tonight’ sign on the Walrus Saloon,” says guitarist, singer and songwriter Herman.

Emmitt was playing at the club with his Left Hand String Band, which already had a reputation locally for playing “bluegrass you could dance to,” Emmitt says.

Herman eventually formed the Salmon Heads, which merged in 1989 with the Left Hand String Band to form Leftover Salmon. They added electric guitars and drums and labeled the music “polyethnic Cajun slamgrass.”

“What really lured me to Boulder was the Telluride Bluegrass Festival and Hot Rize,” Herman says. “Colorado presented a wide-open field. I knew there were people there looking for a more progressive bluegrass sound.”

Black Sabbath and Hot Rize

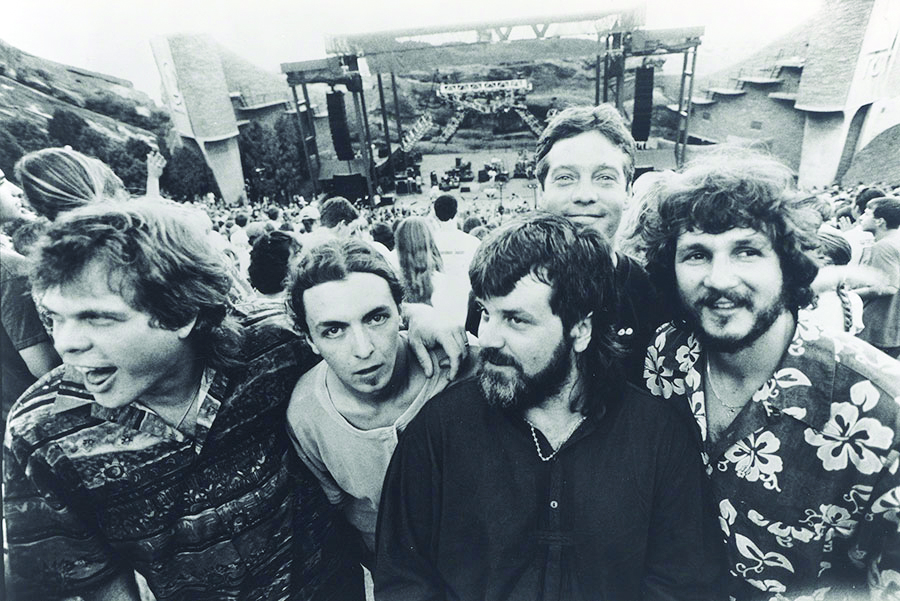

Old Band photo with accordion: Back row, left to right Drew Emmitt, Josie Wales, Mark Vann Front row left to right Glenn Keefe, Joe Joegerst, Vince Herman

Before moving to Boulder, Emmitt’s family lived in Nashville where he was exposed to mainstream country artists like Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash. “Us kids were into rock ‘n’ roll. The first album my siblings brought into the house was Black Sabbath’s Paranoid,” he says.

In Boulder, Emmitt learned to play the electric guitar, and took mandolin lessons from Tim O’Brien of Hot Rize.

“Growing up in that scene as a teenager was great, going to clubs like Tulagi and the Hungry Farmer, and the Rocky Mountain Bluegrass Festival and Telluride Bluegrass Festival,” he says. “The big thing was the openness of people to accept progressive bluegrass and not thumb their noses at it.”

Bluegrass you can dance to

In the 1980s, bands like New Grass Revival were shunned by stodgy bluegrass conservatives simply because they featured an electric bass. Also, grooving wasn’t exactly encouraged in bluegrass.

“When you went to bluegrass festivals, people sat in their chairs,” Emmitt says. “We were part of a movement to get people up on their feet. We were amazed that we could go to places like the Gold Hill Inn and the ski towns and play bluegrass in rock ‘n’ roll venues.”

As Herman notes: “They were people who understood that you could dance to bluegrass and that bluegrass could get rowdy.”

There was a more pressing reason why band members wanted to rock out on acoustic instruments: They didn’t want to get a day job.

“At that time, bluegrass was strictly summertime music, so bands could only tour about five months a year,” Emmitt says. “Along with my parents, everybody, including bluegrass musicians, were telling me, ‘You can’t do this for a living.’ Well, we found out we could play all winter in Boulder, Aspen, Vail, Steamboat and Crested Butte.”

However, that ability was the result of some timely sound technology innovations. Up until the early 1980s, musicians playing acoustic guitars, mandolins and fiddles truly struggled to be heard when playing into microphones.

“There was virtually no way to plug in an acoustic instrument,” Emmitt says. “Sam Bush (of New Grass Revival) was one of the first mandolin players I saw plug in. There were new pickups for the instruments that made it possible to be heard. I could play my mandolin and it didn’t sound crappy.”

Less jammy than some

From its earliest days, Emmitt, Herman and other band members were writing original tunes.

“What always grabbed me about bands were the songs,” Emmitt says. “Hot Rize had great songs. We’re in the jam band genre and I’m thankful for it, but we didn’t get into music to jam on one chord for 40 minutes. We have some long jams, but our music is more based on songs.”

Original tunes like “Troubled Times,” “Liza” and “Highway Song” have become Leftover Salmon favorites that fans sing along to, a fact that still wows Emmitt.

Jamgrass ancestors and descendants

Leftover Salmon knows that it stands on others’ shoulders.

“We’re not even close to being the first band to do what we do, to mix rock and bluegrass,” Emmitt says. “New Grass Revival helped to open the door, along with Hot Rize and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. The Seldom Scene was the original jam-y bluegrass band, but you really have to go back to the Earl Scruggs Revue. Earl was way out on the cutting edge.” That family band, led by the legendary banjoist, played rock songs and featured a drummer.

One major band that counts Leftover Salmon as an influence is The String Cheese Incident. “String Cheese came up watching us do our thing and then went in a different direction and got way bigger than us,” Emmitt says.

When the old friends in Leftover and String Cheese are on the same concert bill, they almost always jam together. “We’ll play ‘Sittin’ on Top of the World,’ ‘Quinn the Eskimo,’ or some bluegrass songs. Like us, they can morph into different styles. When I sit in with String Cheese it feels like the same band with the same kind of concept,” he says.

Leftover Salmon also influenced mandolin superstar Chris Thile of the Punch Brothers. “We definitely corrupted Chris, who came from a very pure bluegrass background,” Emmitt says.” The first time we played the MerleFest festival (in North Carolina), Chris was only 13. He sat in with us—literally, he always sat in a chair when he played. Chris had never plugged in, so I gave him my mandolin and he got up and started dancing around.”

The Leftover future is bright

At the age of 32, Leftover Salmon is as strong as ever, with a lineup featuring Emmitt and Herman plus banjo wiz Andy Thorn, bassist Greg Garrison and drummer Alwyn Robinson.

Leftover Salmon recently recorded a new album at Compass Records in Nashville of some of the songs that influenced the band, including “California Cotton Fields,” a tune recorded by The Seldom Scene.

“It’s sung by our newest member, Jay Starling, who is the son of John Starling, the lead singer of The Seldom Scene,” Herman says.

One highlight of the new covers collection—due out in the fall—is the classic “Blue Railroad Train” with guest Billy Strings. “It harkens back to the origins of the music that inspired slamgrass,” Herman says.

The white-bearded Herman recently moved to Nashville. “I just turned 60, so I thought it was time to finally do a solo album,” he says. “I have a plethora of tunes that are a little more country sounding.”

When Leftover Salmon travels, Emmit says he is usually approached by young musicians asking questions like, “What kind of pickup do you use?”

“It’s the kind of thing I used to ask about,” he says. “It’s pretty cool. Maybe we were the forebearers, but some of it was just good timing.”

Herman agrees. “I’m proud that we played a role in attracting people to this music—listening and playing it. The lesson is: If we could do it, anybody could do it,” he says.

Under yellow leaves Leftover Salmon’s current lineup features, from left, Alwyn Robinson, Greg Garrison, Drew Emmitt, Vince Herman and Andy Thorn plus Jay Starling (not pictured)

***

Email: [email protected]