The warmth of the debut Figueroa album, The World As We Know It, radiates from the first flurried guitar that opens the album; it’s there in every squeak as fingers slide across wound strings, it’s there in the lonesome moan of an organ’s pipes.

The warmth is there despite any instruments. That flamenco guitar that opens the album? Made with a MIDI, every strum, pluck, buzz and squeak painstakingly created by a hand that doesn’t know how to play guitar.

Figueroa is a pseudonym for avant garde producer Amon Tobin, who has long chosen to classify his diverse catalog of electronic music under different projects: hip-hop-meets-drum-and-bass as Cujo, heavy bass as Two Fingers, punked out electronic as Only Child Tyrant, and a master of cutting, splicing, repurposing and modulating under his given name.

“It would have been easier to just learn to play the bloody guitar,” Tobin jokes about his work as Figueroa. But Tobin’s never been one for the beaten path.

Taking cues from the sun-kissed, psychedelic sounds of California folk rock bands like The Byrds, its focus firmly centered on melody, harmony and emotive lyricism, The World As We Know It is Tobin’s most vulnerable work to date, a unique jewel in his crown of accomplishments, and a testament to his mastery of sound design.

And he never intended it to see the light of day.

“I mean, I’m not qualified to make this record, that’s what’s so weird about it,” Tobin says with a laugh. “It was something that I did very much as a personal thing, trying to learn about harmony and songwriting in the more traditional sense.”

The character Figueroa — though it had no name at the time — was born during a period of self-isolation in Northern California. There’d been a break-up, and “there was a lot of tequila going on,” Tobin admits, “so I was just making these songs as a kind of a personal sketchbook of things.”

But the songs sat on a hard drive for nearly a decade as Tobin continued to make music under the Two Fingers moniker with fellow British drum-and-bass producer Doubleclick. Looking closer at this period in Tobin’s professional life, it could read as though Tobin was taking a break from himself, letting eight years pass between 2011’s ISAM, and 2019’s Fear in a Handful of Dust, both released under his given name.

When Tobin looks back, he sees a time when his professional aspirations took on a life of their own, expanding in that exponential, uncontrollable way that great ideas tend to in a capitalist society.

In 2011, things had gotten big for Tobin. Like, 3 tons big. ISAM, his seventh studio album, was also an immersive audio visual show featuring a 25-foot-wide, 3 ton digital installation Tobin built himself. The album was an exploration in the possibility of sound, made from heavily-processed field recordings that provided a wild soundtrack for the digital installation to illustrate. Tobin was riding the crest of the immersive art wave that was about to break in the States, and the industry was eating it up, sending Tobin criss-crossing North America with his enormous creation, and eventually launching an even larger ISAM 2.0 project.

Tobin, meanwhile, was feeling a bit like Dr. Frankenstein.

“I felt quite conflicted about the scale of all of that, even while I was doing it, honestly,” he says. “I appreciated the reach it was giving me, but a lot of careers were being kind of held up by the scaffolding of that project. You suddenly realize that all your agents and managers and their livelihoods are being propelled by this, and they’re all actually making a lot more money than you are to begin with and then relying on you, so they’re pushing you to do more and more of that. At a certain point, you start to realize that you’re working for other people.

“When the scale of things gets to a certain tipping point where you’re finding that you’re doing things to sort of sustain other people’s hopes and dreams and livelihoods, you have to kind of decide,” he says. “Everyone feels you’re very important because you are very important to their livelihoods. So you have to weigh that up against maybe being less important, maybe less significant to people, but then having a greater degree of autonomy in your own world. And I kind of feel like that might be a better fit for me.”

The intimate music of The World As We Know It illustrates Tobin’s decision to turn inward after ISAM. Those first recordings made in isolation in California were no less ambitious than ISAM, no less detail-oriented or laborious, but they were his and no one else’s — a physical expression of the emotional toil of the ISAM project.

“There is a human emotion all the more palpable when expressed through a synthesizer’s limited range,” Tobin said of ISAM when it was first released. “If a piano played this, it would be sentimental. Perhaps it still is a bit.”

His words ring true listening to the opening Figueroa track, “Weather Girl.” A low-action guitar burns through a repeated run, racing like thoughts, never ending, never slowing. In a hushed voice, Tobin wonders: “Do you ever feel like something’s severed / Something’s wrong?” But the track rollicks along, just as the world does, problems be damned.

Contrary to Tobin’s self-assessment, not only is he qualified to make this record, he’s the only one who could make this record, creating guitar work so intricate in some tracks (“Put Me Under,” for instance) that classical players have told Tobin the runs are impossible to play as written. In anyone else’s hands (which is what Tobin had envisioned for the tracks before Tool-producer Sylvia Massy convinced him to keep them for himself), The World As We Know It would still be beautiful, just different.

Brian Eno once said, “Regard your limitations as secret strengths. Or as constraints that you can make use of.” Words Tobin seems to live by.

“I sort of have an idea about creativity being born of limited resources,” he says. “I often think of scratch DJs as a good example of that, where they take a tool like the (Technics) 1210 turn table, and they’re doing things that are so far beyond what that tool was invented for, what it was designed for. And that’s where the creativity is, being able to go beyond the parameters that were set for the thing.”

Aliases, like Figueroa, also play into Tobin’s creative process, allowing him to disassociate a bit from the experience of having to sell his work over and over and over to a world hungry for narrative.

“Over the years, the thing that’s annoyed me the most is whenever you make a record, as soon as you start having to talk about it or promote it, the question always gets asked: What’s the story? As though the record in and of itself is worthless [unless you] attach a bunch of other embellishments to make it palatable.”

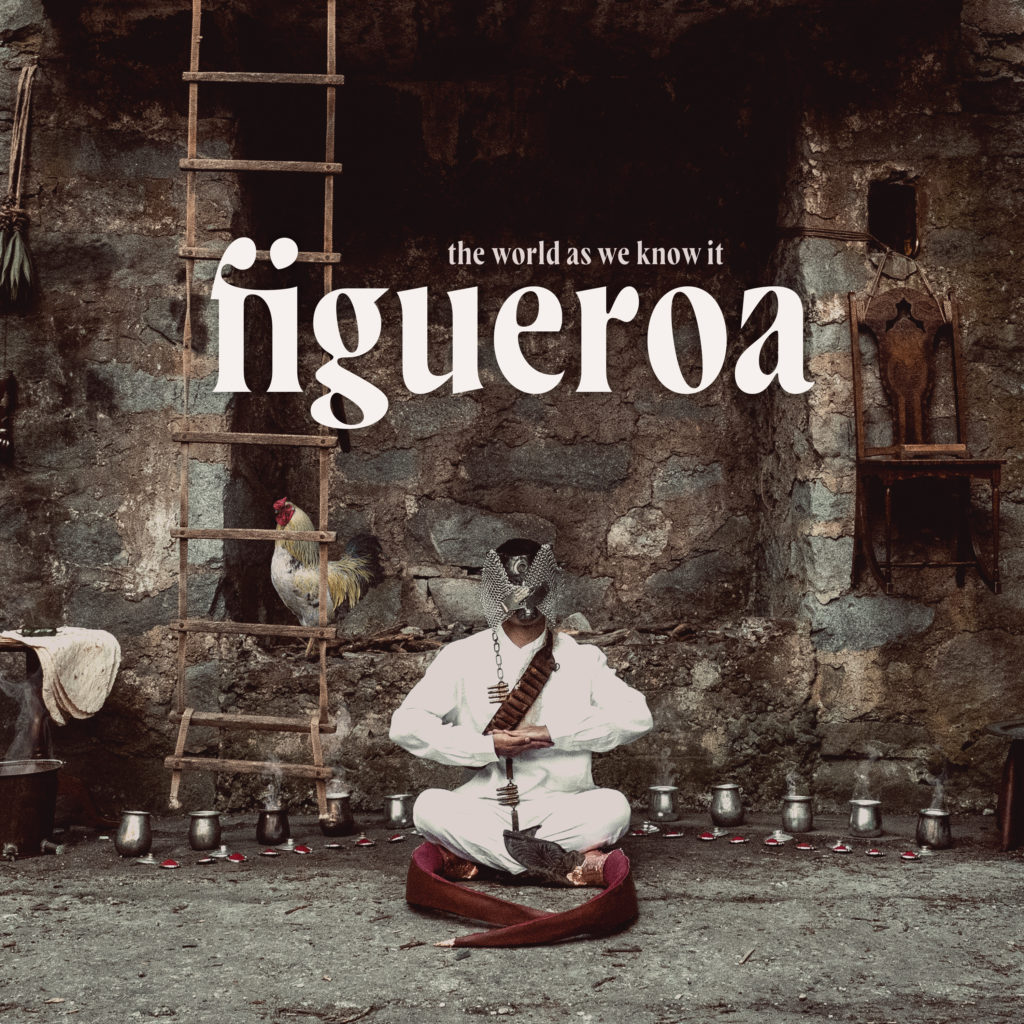

(Figueroa, for the record, is a street near where Tobin lives now in California. A common surname among Latin Americans, particularly Mexicans, Figueroa touches a bit on Tobin’s proclivity for listening to Mexican radio during the time when the album was made.)

Despite being made nearly a decade ago, The World As We Know It is a timeless record, versatile enough to be read as a break-up album, a depression manifesto or, as Tobin himself suggested, a treatise on the plague that is humanity.

“Some of the themes lyrically in this record somehow lined up with things that are going on right now, like us being put in our place by a virus,” he says.

“What can I say / Yesterday’s gone / Don’t be a bitch,” he sings on the penultimate track of the album.

A mantra for 2020 if ever there was one.