Luz Lopez gazes into the tea cup, studying the leaves and “their soaking shapes.” The Platte River rushes at her back and all around, Denver’s chile harvest pulses, crowds moving through “the city’s liquid center illuminated in green and blue lights.” It’s 1933 and the 17-year-old sees three foreshadowing images inside the cup: a clam, an owl, a brick.

She glances up at her client, a white woman tightly bundled, then peers back down to witness “something strange, off-putting, the tea leaves seeming to drift like a blizzard over golden plains until Luz saw a place she hadn’t before,” and her vision snaps to something so startling she suddenly lies, gives her client vague answers about what she sees, what it means.

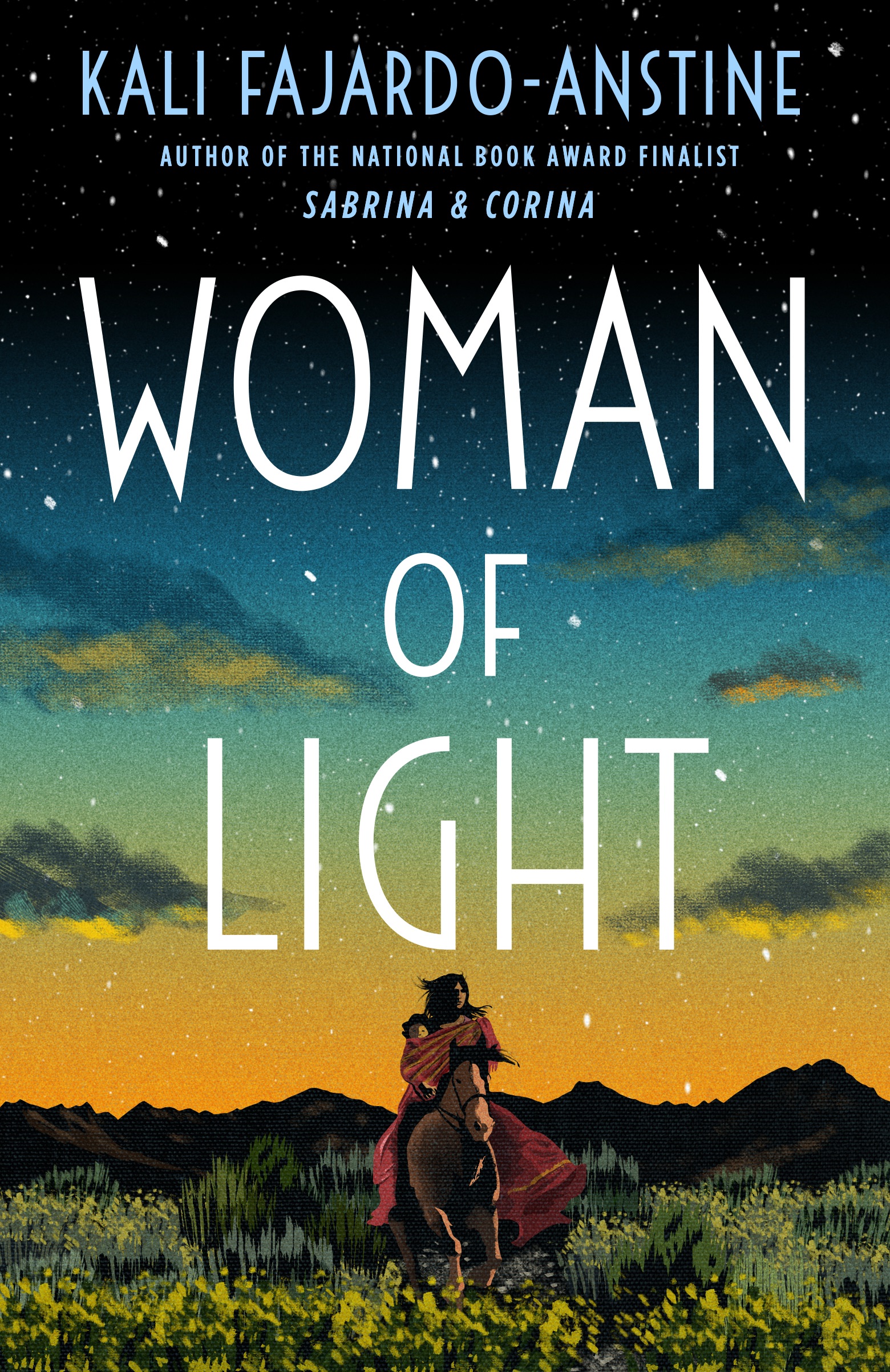

Luz, protagonist of Woman of Light, Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s debut novel, dips in and out of that which lies beyond the edges, sees scenes as they might have or could have happened at various points within the arc of five generations in Colorado—not unlike like the author herself oscillates through time in the storytelling of Luz becoming a woman, losing her brother and navigating 1930s Denver as a laundress-turned-law-office-secretary with her complex family histories in tow.

The story’s root curls around the last generation before contact is made with Anglo peoples in southwest Colorado. The vines of the family’s DNA then reach toward Denver, slowly unfurling one generation at a time like flowers toward the sun. Luz arrives in the Mile High City at age 11 from Huerfano, the town where her mother landed after leaving the Lost Territory, the region where their indigenous ancestors tried mixing with Anglos but were cheated and brutalized. (“Again and again her husband explained … no human being can possess land. Again and again Simodecea watched as new tents went up throughout the property, the canvas shacks fluttering her eyesight like the blurred edges of reality just before a person faints.”)

Mexican sharpshooter Simodecea, Luz’s grandmother, is another strong female character (classic Fajardo-Anstine, readers of the writer’s short-story collection Sabrina and Corina will note) who is often thrust into protection mode, forced to rely upon her instincts and deep inner wisdom—part of the “real intelligence” the girlfriend of Luz’s aunt once describes, “that comes from our grit, our ability to read the world around us.”

It took nearly 15 years for Fajardo-Anstine to publish Woman of Light, hotly anticipated after Sabrina and Corina won a 2020 American Book Award (among other accolades) and garnered glowing reviews from the powerhouse pens of Julia Alvarez and Sandra Cisneros, whom Fajardo-Anstine thanks in her acknowledgements for Woman of Light. The 35-year-old author grew up in Denver, dropped out of high school, got a GED, then dropped out of her first master’s program and received an MFA from the University of Wyoming.

“[Writing] this book taught me to look at our city and our space in a generational way—in a way that’s textured and deals with history over a long period of time,” Fajardo-Anstine says. “I didn’t just move to Denver and decide that I wanted to set stories here, I’m a person who has Indigenous ancestry. My family has been here since time immemorial in some ways, and they’ve been in Denver proper since the 1930s—it’s the backbone to my understanding of the entire world.”

As such, the novel’s spine is “a multicultural, foundational Denver—a Denver that speaks many languages, a Denver that’s many classes—a look at the city that I don’t think many readers have ever seen before,” she explains.

“It’s important to think about readers across the world experiencing Colorado from the perspective of a mixed-race Chicana of Indigenous ancestry.”

In Luz’s world, violence is around every corner, and it’s the type of violence that sets Fajardo-Anstine apart from what’s largely dominated the concept of “Western literature:” tales told about Anglos and Indians in and around the Rocky Mountains mixing men with booze and rugged landscapes with horses.

“So much of our identity as a Western space has been defined by the cowboy narrative, the myth of the stoic outlawed cowboy figure,” Fajardo-Anstine says. “This is going to be the first time somebody is coming to the American West in a way that is not the stereotype mythology.”

Instead of the sensationalized Bonnie-and-Clyde violence that Fajardo-Anstine ironically inserts as a simmering backdrop to the novel, Luz’s brother receives a “beating that sounded like bones garbled in a sack” for speaking Spanish at school; a young woman fears “the things I will be forced to do in order to feed myself and Mama” after her brother is murdered by police officers; Simodecea feels “her husband’s swampy shallows on her fingertips” as he dies in her arms after a suited man arrives and “gun blasts sprayed bullets across the land.”

“Better get used to it,” another of Luz’s aunties advises, stitching the face of her brother after a white mob used bricks to bash his skull during a party in town. “I won’t make you fix him this time but it’ll serve you to learn.”

In effect, Fajardo-Anstine portrays the rippling, compounding effects of Anglo settlers on so-called Colorado; between scenes bubbling with new love and hope for better futures, she forces the reader’s gaze to hold on the worst of it. Luz and her steadfast aunt Maria Josie learn, in most cases, it’s best to bury the past, stomp good and hard on it, then use the solid ground for a big step forward.

For Fajardo-Anstine, the past is more elastic. The time period that frames Woman of Light—1860s to 1930s—is “a mirror for today,” she says. Maria Josie indeed comes home often with hands nicked and scratched after long hours laboring at the nearby mirror factory. As Fajardo-Anstine loops between decades, she doubles back to fill in plot texture, then glances forward, tantalizing what’s to come—it’s like the mirror’s been dropped, a kaleidoscope spread of stories arranged together, aesthetic and dynamic enough to conjure a quote from Joseph Conrad, which Latin American literary giant Mario Vargas Llosa once used to describe the work of Gabriel García Márquez: “Circles, circles; innumerable circles, concentric, eccentric; a coruscating whirl of circles.”

Thanks to her parents, Fajardo-Anstine says her childhood was “steeped in books.” Her mother is a writer, her father an avid reader. “When I would get depressed, my dad would actually leave books outside of my door, as sort of like a treat,” she says, and as one of seven children, “reading was something I could do alone.” Besides Garcia Marquez, she grew to love authors like Sylvia Plath, Khalil Gibran and Elizabeth Bishop.

Since elementary school she’s been writing stories, and when she turned 16, she started working at West Side Books in North Denver, where she’d continue working off-and-on until age 30. Enmeshed in words, Fajardo-Anstine absorbed everything she could, feeling authors like Willa Cather, Toni Morrison, Katherine Anne Porter and Alice Munro weave themselves into her “craft DNA,” describing the women as her literary ancestors: “Writers whose style and prose have made an imprint on me.”

Like Munro relies on Ontario as a vivid backdrop for her fiction and Morrison uses configurations of space and community to impress alienation or belonging, Fajardo-Anstine digs into Denver through the senses—insects chirping, factories whizzing, people gossiping, building upon the scene-setting strength she exhibits throughout Sabrina and Corina. Some chapters in Woman of Light—like “Women Without Men” and “La Llorona”—could stand alone as satisfying short stories, but larger themes clearly bind the chapters. The inverted evolutionary trajectories of voice and sight throughout the female lineage, for example: While their ability to see into the edges of life strengthens over time, as the women grow farther from their pre-Anglo matriarch, the Sleepy Prophet of the Lost Territory, their voices weaken. Once a “musical sound in their throats,” life in a small shared apartment in Denver leads “a growl … trapped inside [Luz’s] bedroom, inside her throat.” There are times when “she’d open her mouth to speak but could only picture white moths fluttering from her lips.”

Early in the novel, the protagonist contemplates “the rich, the doctors and lawyers, businessmen and silver-tycoons” and realizes she “often felt she and her people were only choking on their leftover air.” Fajardo-Anstine, by contrast, is taking a big gulp and shouting herself far and wide with Woman of Light, an energy she infuses in a pivotal scene shortly after Luz and her brother leave their mother at the Huerfano mining camp and arrive in Denver to live with their aunt Maria Josie.

The young siblings are crossing blocks, writing a map of the city into their minds when they run into one of the neighborhood’s most complex characters, who points to the mountains and tells them that way will always be west before pointing to the plains, which always run east. Then he gets them to shout in unison, “THIS IS MY CITY!” timidly at first, with the young girl soon amassing courage: “They yelled together until their voices boomed, high and arching, rattling streetcar cables and smoggy windows, soaring between stone tenements and factory tufts. This, she repeated, is ours.”

So, too, Fajardo-Anstine claims her voice and her words, printed on pages and now translated into languages around the world—for language matters; it crafts history. If lived experiences accumulate like silt on river banks, the so-formed clay is shaped by language and hardened by time; history is constructed by human hands. It matters which palms, eyes and spirits do the sculpting.

One western Colorado town, for example, currently has a brochure on its website, attached to the “Historical Information” section, which reads: “With the departure of the Ute Indians, a resilient bunch of settlers and entrepreneurs took up residency in the new town.” Words can wield violence, too, and Fajardo-Anstine has no patience

for euphemisms.

When Pidre (the Sleepy Prophet’s grandson, Simodecea’s husband) is walking through a bustling fairground for the first time in his life (soon after Anglos have expanded across their valley), the suffocating knot that Fajardo-Anstine has been trying to unravel is pulled taught: “It was in that moment that Pidre realized he had entered the strange world of Anglo myth,” she writes. “Pidre came from storytelling people, but as he passed a big top devoted to the reenactment of Custer’s Last Stand, he couldn’t help but think that Anglos were perhaps the most dangerous storytellers of all—for they believed only their own words, and they allowed their stories to trample the truths of nearly every other man

on Earth.”

Email the author with comments at [email protected]