I don’t take notes as Arthur Secunda talks to me; I’m too focused on hearing him, and it strikes me that the scratching of a pen against paper would make it harder. We’re alone in a small meeting room in the front lobby of ManorCare, where the 91-year-old artist lives, late afternoon sunlight gilding the room. It’s quiet, but I slide my recorder closer, lean in and tilt my ear more toward the sound of Secunda’s voice.

Parkinson’s disease has made Secunda’s voice softer, breathy. It makes his once steady hands tremble. Macular degeneration has severely limited his eyesight — and yet Secunda continues to create art, just as he has for the last 80 years.

“I used to enjoy details, geometry, all that,” he says, slowly drawing a small circle on the table with one hand. Coral-colored polish on his nails is chipping, but vibrant. “I can’t do that anymore. I have to rely on other people. The simplest things… It’s very frustrating, but you know, the result is what counts.”

A small but stirring collection of Secunda’s more recent sculptures and mixed media paintings is currently on display at Bricolage Gallery in Art Parts Creative Reuse Center. The collection — Everyday Magic — pays homage to the things we often pay no mind at all: shoelaces, coins, paperclips, fire wood… even Secunda’s own hair makes its way into one painting.

It’s an intimate show, with bits of Secunda’s personal history scattered throughout like breadcrumbs forming a trail to the artist’s heart. There’s “Art Forest,” where Secunda’s old paint brushes seem to reach upwards in search of the light of a blue sun (one of his granddaughter’s many figure skating medals). In another, the skeleton of the Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow fame — now missing his right foot — hovers about the stalactites and stalagmites of the caves of Dordogne, France. Secunda spent much of his life and career in France, and the caves of Dordogne, with their prehistoric drawings, could be considered one of the world’s first art galleries.

Then there’s “Music Machine,” a towering sculpture built around a working music box — an enlarged version of the kind with the little ballerinas that pop up when you open the box. Gilded buttons and knickknacks of indefinable origin cover the machine, which forms a steeple of sorts from a xylophone and a guitar head. On the back door of the music box is a message from Secunda:

“This kalliope music machine compiled 1964 is dedicated to those that love music and beauty in all its forms.”

Perhaps it’s here, within this sculpture, that we find the beating heart of Arthur Secunda: artist, jazz pianist, creator, lover of life.

Everyday Magic is a snapshot of a life filled with magic. It proves that Arthur Secunda has never taken much of anything for granted, least of all his ability to create.

From the beginning

Born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1927, Secunda describes his early childhood as “terrible.” His father died when Arthur was just two, leaving his mother the nearly impossible task of supporting a child on her own. As a result, Secunda went to live on his Ukrainian-born grandmother’s chicken farm.

“So much anti-Semitism everywhere,” Secunda says of the late ’30s in Jersey. “The Ku Klux Klan was there. I was referred to in class as the ‘Jew boy’ by the teacher. It was just a very difficult time without my parents, working on the farm.”

In 1935, when Secunda was 8, he reunited with his mother and the two moved to Manhattan — 71st and Broadway — where the young artist’s life drastically improved. There he was surrounded by art and music and a stream of immigrants (many of whom spoke Russian, as Secunda did) and culture.

He recalls walking down 57th Street one day and hearing live music coming from inside the nearby building. A security guard noticed the young man listening and told him it was Sergei Rachmaninoff. The building was Carnegie Hall.

“He let me stand by the door and listen,” Secunda says of the guard. “Things like that just don’t happen anymore.”

The young Secunda also developed a taste for jazz. He started learning to play piano at 10, and eventually began to mimic the sounds of the “boogie woogie” records of the ’40s that he and his friends loved to listen to and analyze.

By the time Secunda was a teenager, he was steeped in visual art as well, having made his first sculpture at around 10 years old. He traveled to Detroit after being accepted into Cass Technical High School, where he met and befriended fellow artist Ray Johnson, a soon-to-be pioneering figure in the pop art movement. After Secunda returned to New York upon graduation in the mid ’40s, he began a decades-long mail correspondence with the Detroit-based Johnson. The two wrote letters filled with cartoon-like drawings and captions, many of which Secunda still has today. In these letters, Johnson often asked Secunda for any celebrity ephemera Secunda could get his hands on in New York. Johnson credited his correspondence with Secunda as the beginning of the mail art activities that would typify his artistic career.

Secunda joined the Air Force in 1946. As an artist, he “drew cartoons for Air Force Magazine, painted nude ladies on airplanes, [and made] portraits of generals.” The G.I. Bill opened up new educational opportunities, though not all of these experiences were as edifying as his time at Cass Tech. He spent two “conservative, uninspiring, stultifying” semesters at New York University studying art before moving on to the far more enriching Art Students League of New York, where he studied painting with Harry Sternberg and Julian Levi.

Eventually Secunda made his way to Europe. It was, in a way, a homecoming for Secunda’s soul. In Paris and Rome, he found the teachers who would instill in him the business of art, particularly Russian-born sculptor Ossip Zadkine and painter Andre L’hote.

Zadkine taught Secunda to treat art like any other job: Begin your day at a set time every morning; set up your studio in a functional way; persevere through the hard times; and never forget the value of your unique creations.

“They were so dedicated, so sincere,” Secunda says of the artists he worked with in Europe in the late ’40s. “Sincerity is something that in America we laugh at sometimes, but in Europe it’s very important.”

Always eager to explore new artistic terrain, Secunda went on to work at the Esmerald Escuela de Pintura y Escultura in Mexico City, where he learned the art of woodcarving and woodcut printing.

He’s been making “junk art,” as he calls his bricolage works, since the ’60s when he was living in Los Angeles. His studio was close to the Watts neighborhood in south LA, where rioting broke out for six days in August 1965. Neighbors brought him debris to work into his art.

As someone who’d personally experienced discrimination, Secunda followed the Civil Rights movement with empathy — and horror. Over the eight years following the Watts Riots in LA, Secunda documented subsequent violence and bigotry across the nation through a series of approximately 50 paintings, collages, sculptures and graphics.

“Arthur will never say that he’s a political artist,” says longtime friend and LA-based filmmaker Matteo Marchisano-Adamo. “But a lot of his work deals with political ideas and circumstances and the actual physical objects [of political unrest].”

Marchisano-Adamo has spent the last 20 years getting to know Secunda after the two were introduced through the Phoenix, Arizona, chapter of the French Alliance. (Secunda lived and maintained a gallery for many years in Scottsdale, Arizona.)

“I asked him questions about politics once and he said, ‘Well, you know, if I do a painting of two people talking in a cafe in Paris, that’s a political painting.’ So for art, it doesn’t have to be about the Watts [Riots] in order to be political. [His art] kind of transcends that. He doesn’t think in boxes.”

To the end

Secunda spent the next half a century or so traveling, raising his children, creating, teaching, writing, curating and editing. He became an instructor and lecturer at UCLA and a curator of education at the Santa Barbara Art Museum. He produced a weekly TV program called Arts of All Times and was the founding editor of the renowned Artforum magazine.

Today his art can be found in permanent collections the world over, from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to the Library of Congress in D.C. to Tel Aviv Museum in Israel. Museums across Europe hold pieces of Secunda’s work, as do private collectors like C. Edward Wall.

In 2012, Wall, a longtime friend of Secunda’s and perhaps his biggest promoter, helped fund and found the Arthur Secunda Museum at Cleary University in Michigan. There you can see much of the colorful, abstract landscape art for which Secunda is often recognized today.

It’s a long and storied career that Marchisano-Adamo desperately wanted to capture on film. But for much of their friendship, Secunda preferred to talk about his artist friends, like Ray Johnson. It wasn’t until 2015, after Secunda had been living in Boulder for more than a decade, that he invited Marchisano-Adamo out to film a documentary about his life and work.

The film, Ten Days with Art, is an intimate portrait of an artist who refuses to stop creating — not because of any egotistical need to be known, but simply because it’s what he must do. Secunda is built to make art. It pours out of him, and it seems there is no force other than death that is capable of ending his creative output.

But it does take help these days, though that isn’t hard for Secunda to find.

Arizona-based mixed media artist Joseph Breton has known Secunda — whom he lovingly calls Arturo — since the ’80s, and the two have been making art collaboratively since the ’90s. Just five years ago, Breton spent weeks with Secunda in a large-scale garage in Scottsdale working on a 10-by-65-foot painting that now hangs in the Arthur Secunda Museum.

Bottom: Breton (left), Secunda (right) Photo courtesy of Joseph Breton

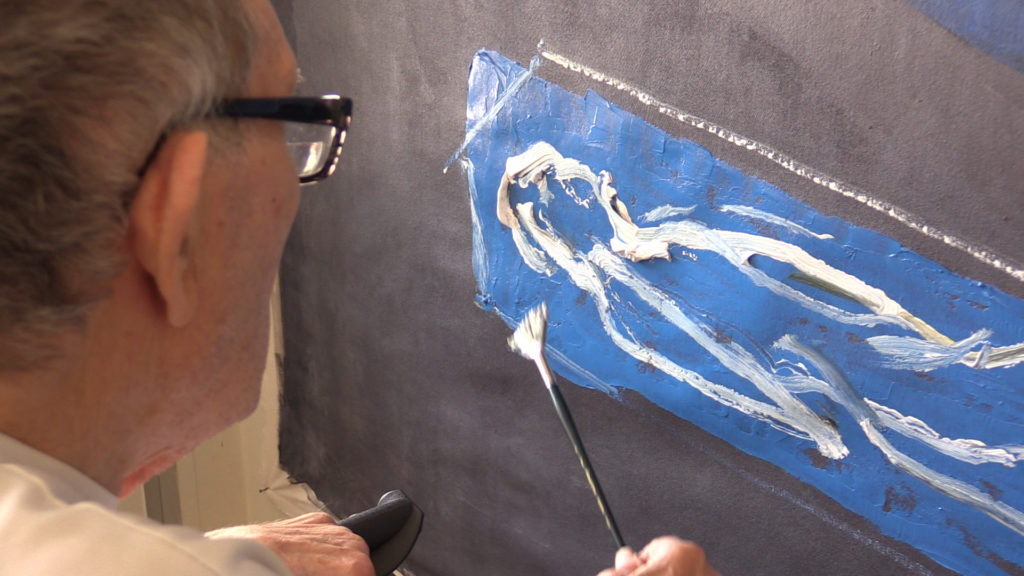

Ten Days with Art captures the familial relationship between these two artists as Breton aids Secunda with painting some of the finer details that Parkinson’s has made nearly impossible for Secunda to complete himself.

“In doing this [particular] painting that you see in the documentary, he wanted me to paint but I was determined not to participate. I wanted him to do it, but I ended up helping him,” Breton says. “But I maintained this was his painting, it was his vision. When we completed the painting, when it was time to sign it, he gave me the brush and said, ‘You sign it first.’ I said, ‘No, it’s your painting, your idea. I only assisted.’ I made that point clear.”

Secunda worried that his friend was embarrassed by the work.

“I’ve never been embarrassed by any of the work I’ve done with Arturo,” Breton says, his voice heavy with the weight of his emotion. “That particular painting, the reason for not [signing it] is because … that painting captures the soul of the artist as he’s reaching his diminishing years. Matteo’s plan for the film was to depict an artist, a well-known, accomplished artist at the end of his years. And the difficulty that he had with holding the brush, opening the jar of paint, executing the brush strokes, and that was the end result.

“That’s why I could not sign it — would not sign it.”

Breton and Marchisano-Adamo believe the core of Secunda’s success as an artist rests with his passion for and appreciation of life.

“He has alway been a very unselfish individual,” Breton says. “He is so rich in knowledge, about technique, about art, about markets, about everything. Arturo seemed to be the only kid on the block who wanted to play. Many other artists, they don’t want to talk art, talk technique. I get excited with Arturo because we talk about art.”

“He doesn’t care if he’s showing at the LACMA or Golden West (assisted living),” Marchisano-Adamo adds. “It means so much for him to be an artist, to be among those who came before him, to advance art in some way or to give some wisdom for the art. He feels honored to be part of that and he should. His contribution, I feel, is kind of like an American secret.”

For more information about the documentary Ten Days with Art, visit matteomarchisanoadamo.com/ten-days-with-art-documentary

ON THE BILL: Everyday Magic: Mixed Media Paintings by Arthur Secunda. Art Parts Creative Reuse Center, Bricolage Gallery, 2870 Bluff St., Boulder. Through April 6.