During the early years of the AIDS epidemic in America, with Ronald Reagan conspicuously devoid of public thoughts on the matter, art began to fill the silence.

There was the “Silence = Death” graphic, its pink triangle a nod to the symbol gays were forced to wear in Nazi concentration camps. The graphic became emblematic of the crisis (both the viral crisis and the manufactured morality crisis that kept conservative leadership from addressing the virus). Then there was David Wojnarowicz, the multi-hyphenate artist and activist whose black-and-white portrait with sutured lips, blood trickling down his chin, gave grave physicality to the concept of deadly silence.

Derek Jarman took a life-focused approach. After the filmmaker was diagnosed HIV positive in 1986, he began planting a vibrant garden at his blustery home by the sea in Kent, recording the process — along with stories from his life — for the memoir Modern Nature. The garden lives on today, more than a quarter century after Jarman’s death in 1994.

The silence from the top is different today. Trump discusses this virus (though he failed to do so for more than a month when it surfaced), but refuses to address the tens of thousands of confirmed deaths (more than 80,000 at the time of writing) stemming from COVID-19. And again, art will fill the deadly silence.

Art will also fill the space between us, bridging the physical chasms we’ve created to stop the virus from spreading. That’s the goal of a new fund for Boulder-based artists, The Creative Neighborhoods: COVID-19 Work Projects. With funding from the City of Boulder and nonprofit organization Create Boulder, the fund is designed to support artistic work that reinforces the “social infrastructure” of our community.

Mandy Vink, administrator for public art at the City of Boulder’s Office of Arts and Culture, says the idea was based on Works Progress Administration, or WPA, projects of the New Deal era that helped the unemployed get back to work quickly on projects that benefited an entire society drained by the Great Depression. (Boulder High School was a WPA project, as were many of the trails and lodges on Flagstaff Mountain.) With Creative Neighborhoods, the artists create works that engage their neighborhoods — from a distance, of course — whether that neighborhood is a physical block of houses on a street or a community of people within the broader Boulder population.

The fund, which topped out at $40,000, provided $599 to 66 artists, an amount that placed “no additional paperwork, no taxation, no extra burdens” on the artist, Vink says.

The scope of the work is varied, from textile projects that document the number of confirmed COVID cases and deaths, to oral histories about how the pandemic has impacted Boulder’s black community, to graphic novels, to geocaching for seed packets. But each project has resilience built into its DNA, the notion that we’re in this together, even if we can’t be together. While the art museums may still be closed, art is always open.

Art therapist Cathy Malchiodi wrote for Psychology Today, that for her, the “true purpose of art is one of resilience, not of pathology or mental illness.”

“It is why humankind has continually returned to art making as one way to reparation and recovery from the inescapable physical, emotional, interpersonal and spiritual challenges of life,” she wrote. “In other words, art expression and the creative process are really manifestations of the drive toward health and well-being, not merely signposts of repression, projection, [or] displacement … As [French artist] Louise Bourgeois noted, ‘Art is a guarantee of sanity’ — it is a human way of self-actualizing rather than pathologizing the potential of one’s life.”

Heather D. Schulte — “The Situation Report”

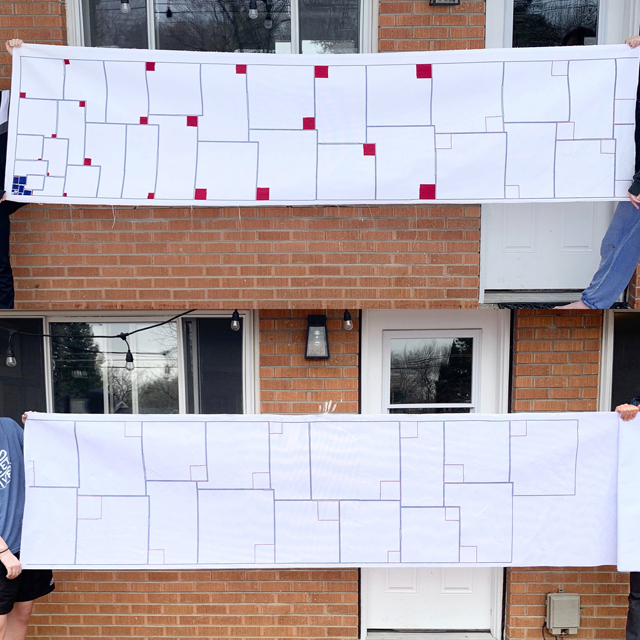

Heather Schulte always gets her best ideas at night. Late one night at the start of the pandemic — struggling to sleep after she’d made sure to purchase enough groceries to support her family for the next few weeks and figure out what school was going to look like for her two kids — the fiber and ink artist remembered a “huge roll” of cross-stitch fabric she had tucked away.

“I thought, what if I just start stitching the [confirmed COVID-19] cases every day,” she says over the phone from her home in South Boulder. “And so it started off really simple.”

But it would soon become overwhelming to keep up with the numbers. Schulte began by using U.S.-based data from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) daily “Situation Reports,” making one blue stitch for every confirmed COVID-19 case, and one red stitch for every confirmed COVID-19 death. By March 13 the numbers were climbing so fast she could no longer stitch every case in one day so she switched to stitching an area that represents the cases for that day. She soon realized that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), which provide data to WHO, does not report on weekends. On March 21 she began using data from Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, which does account for weekends. By April 9 it became impossible to stitch each death, so those too became a representation by area.

Schulte estimates it’s taking her between two and three hours a day to complete stitching the representations of cases and deaths.

“It’s been fascinating paying close attention to the way the numbers are reported, whose numbers are reported, when they’re reported, how they’re reported,” she says. “There is political shaping to that: who has access, who doesn’t. Who has testing, who doesn’t… I mean, the numbers aren’t accurate because we don’t have comprehensive testing.”

Then the numbers became reality. Schulte’s uncle started to show symptoms of COVID-19 on April 11 and was taken to a hospital on April 13. She says he died within 12 hours of admission.

“It was almost too much to take in and understand and comprehend,” she says. “And just not to be able to be together with people, it added a whole other layer onto this thing that I was working on because it was just like a document, and now it’s kind of developed into a memorial or a vigil, a way of marking not just numbers but people.

“As the numbers kept getting bigger, it really hit home how impactful the situation is,” she says. “So many people are experiencing this very same thing, some of whom are experiencing it in a much more difficult way, that don’t have access to so many things that I do or whose loved ones are suffering in the hospital for who knows how long and they can’t go visit them.”

Schulte has already recruited stitching help from a couple of friends in the neighborhood — keeping distance, wearing masks, using hand sanitizer. Once social distancing protocols are lifted, she hopes to invite more people to stitch with her to “fill in the spaces.”

“In a time when physical touch, even mere proximity, is limited to those with whom we live,” she says, “it feels essential to plan intentional steps to reconnect with our communities.”

See more about “The Situation Report” and Heather Schulte’s other work at heatherdschulte.com. Please contact Schulte if you have red or blue embroidery thread available for donation.

Will Betke-Brunswick — A hand-drawn COVID zine

Will Betke-Brunswick has long been drawn to the do-it-yourself aspect of zines.

“Anybody can make one,” says the transgender and nonbinary artist. “You don’t have to be trained as an artist. There’s a long history of zine culture where people are sharing homemade zines about whatever they want. I sort of come from both that side and from a long appreciation of New Yorker cartoons.”

Betke-Brunswick (who prefers to use a mix of masculine and gender neutral pronouns) has used this zine-aesthetic-meets-punchy-one-liner approach to comic creation to document his journeys through the world as a transgender person, forced to prove to the government that he used to be a woman in order to justify not having registered for selective military service, and grappling with the health care system to get access to birth control.

“I think that art is my number one way of processing whatever I’m feeling,” they say. “Hard things, easy things, funny things, sad things. That’s been huge for me personally with processing things, but also wanting to create and share and make more visability for queer people and having it not always be this sad and dramatic journey, which is not my experience. My experience is much more whimsical and funny and supported.”

Betke-Brunswick will bring that same aesthetic to an eight-page zine for the Creative Neighborhoods project, focusing on the day-to-day realities of living under stay-at-home orders, from suiting up in gloves and a mask for a quick trip to Ideal Market near their home in North Boulder, to anxiety-inducing phone conversations with parents about death.

“I have a real hope that humor can contribute to resilience,” they say. “The little funny moments we’re all experiencing within a larger tragedy is a way to connect or process. I have a longer book-length project that I’m working on that’s about my mom having cancer and dying and it’s definitely sad, but there’s a lot of humor in that, in the little weird moments of going through something sad. I think that’s what makes us resilient, being able to laugh about it.”

Betke-Brunswick plans to distribute about 25 copies of his zine to homes in his neighborhood in North Boulder, but you can check out more of their work at willbetkebrunswick.com.

Katrina Miller — How COVID-19 is affecting Boulder’s black community

When Katrina Miller moved to Boulder more than 20 years ago for college and was looking for a black community to connect with, she was directed to the Second Baptist Church.

“Boulder is very transient,” says the independent filmmaker who operates under Black Cat Video Productions. “Most of the black people that come to Boulder are here for university or work assignment, so they are just passing through, so if you do want to find people who have been here for a long time you go to the church. [Second Baptist Church] has been around for over 110 years. This is the place where people not only have spiritual services, but barbecues, weddings and graduation parties. This has been the place where everybody gets together to have community and all of a sudden the doors have been shut on that. The thing is, these people who have been here and stayed here, their children have moved away. Elderly people in the black community are very isolated and not technologically savvy, so their quality of life has really deteriorated.”

On May 15, Miller will begin production on a short film following the impact of this isolation within Boulder’s black community through 91-year-old Second Baptist Church member Elmira Davis, who, in Miller’s words, “seems as though she is fading without a song to sing to God among her brothers and sisters.”

“Elmira is fascinating to me because there are five different choirs between California and Texas she helped start,” Miller says. “That’s what her life has been built on is creating communities. She moved to Boulder in 1962. Boulder was still segregated in some parts at that time, businesses were still segregated: The Sink and Buchanan’s and the Boulder Theater just to name a few. Boulder was very racist at the time, just like much of the rest of the country. [Second Baptist Church] must have been a very important hub [at the time], a place where everybody could gather to have a sense of community. Having that ripped away today, it makes me sad.”

As a black woman living and working in Boulder, Miller details the daily exhaustions of moving through the world as a minority: It’s as simplistic as not being able to find a good hairdresser and as complex as explaining racism to her children.

“When you don’t see any other reflections of yourself, you feel on the outskirts of the white community and you end up seeking out other people and it doesn’t matter if the people you find are in Boulder or in Gunbarrel: You’ll get together. That’s the thing about the church: the members live in all areas of Boulder County.”

Which makes Miller’s project a bit different from the others in that her “neighborhood” is all of Boulder’s black community.

As Miller has made her home in Boulder, she’s searched archives high and low for information about the city and county’s historic black population, finding precious little, she says. So while her film unites a community severed during this pandemic, it also serves a higher purpose as a small rectification, a mere drop in what should be an ocean of black history.

“We are the people making history right now,” she says. “I do feel like we are capturing Boulder in a way we’ve never seen before and may never see again.

“That elderly community has seen so much, gone through so much,” she says. “To have to go back and retreat to your home after all of that work… it’s heartbreaking. It makes me worry how this is going to go at the end.”

Find more information about Katrina Miller and her work at blackatvideoproductions.com.

Kevin Sweet and Laura Hyunjhee Kim — Geocaching with custom seed packets

Kevin Sweet and Laura Hyunjhee Kim are both working on art-focused PhDs right now, but don’t expect esoteric projects from these two.

“A lot of conversations we share revolve around sharing ideas and collaborations that reach beyond just the arts,” Kim says over a Zoom call with Sweet. “We talk about what is high art and what is low art, what is art outside of the gallery? And how can we involve more people.”

Together, Sweet and Kim are creating custom seed packets they plan to disperse around their shared neighborhood in Boulder (“the 80302 zip code,” Kim says) for people to find, either by geocaching or by walking around and looking — like an old-fashioned scavenger hunt.

They plan to disperse about 100 packets made with biodegradable beeswax, filled with Sugar Anne snap peas, which don’t require a lot of sun to grow.

Much like their PhD work, this project seeks to expand the notion of art.

“For us it’s about the experience of being able to share this kind of mutual experience,” Sweet says. “We share this idea of artwork, of what the artist produces, as something that is fundamentally incomplete. It’s incomplete until it is engaged with by the broader public. We’re setting up a circumstance through which other people are going to take it into their homes, into their lives, and they’re going to do with it what they will, what they want to creatively do.”

Each packet will come with a small explanation of the project and a link to a website where people can share their experience, including their journey with their new plant.

“We’re not trying to distract people from what’s happening, but also part of resilience, I think, is having purpose, having hope, having something to look forward to,” Kim says. “Even if it’s like, OK, tomorrow, what are we going to do for this plant? Are you going to water it? Are you going to dance with it? Are you going to make a song or even write a story? So the seed’s not just a seed but also a metaphor for going forward, for having something to look forward to. I think that’s so important and that’s part of what has driven us to think beyond ourselves being artists but more as instigators to help kind of create that space for families to bond.”

Find more information about Kevin Sweet at kevinjsweet.net/info and more information about Laura Hyunjhee Kim at lauraonsale.com