“Put chile and some water into a saucepan with bullion, garlic which is diced, and salt and pepper and onion which I don’t have and won’t mention anymore because I miss it, and you shouldn’t ever be anyplace without it, I don’t care where.”

– Simon Ortiz “How to Cook a Good Chili,” Woven Stone

I made it surprisingly far through life without thinking deeply about onions. It took an acid trip in college, during which I watched my friend Wayne fry an onion that had been cut in half. We stood transfixed as it slowly melted in the pan. I could feel it was a profound moment, but it would be years before I understood the onion’s many layers of flavor, and its fundamental importance to cooking.

A decade later, when I read the Simon Ortiz poem (quoted above), it resonated because I knew he was right, that you shouldn’t ever be in any place without onion. But I still didn’t know how to cut an onion. I could hack one, with too many strokes, into large, awkward pieces, but I had no system.

I finally learned how to cut an onion from an old chef friend when I was helping him cater an event and he was bossing me around. He told me to cut the onions just so. In the days and weeks that followed, I realized that this is the only decent way to cut an onion.

Cut the ends off the onion, peel it, and slice in half from tip to tip. Lay the flat sides down and make a series of thin parallel slices, about ¼ inch apart, along the tip-to-tip axis. Each thin slice is fragile, ready to fracture into concentric arcs with a mere tousle. If you need them minced, it’s just one more step. After making those parallel slices in the onion halves, hold the pieces together with one hand, turn the held-together half 90 degrees, and cut ¼-inch slices perpendicular to the previous ones. The onion will fall apart like confetti.

The power of an onion is compounded by its dual personality. While a well-cooked onion gives its flavor selflessly, bringing harmony to a dish, raw onion is about contrast. Its presence is more of a fiery assault by an army of white lightsabers.

Sometimes I find myself running to the cutting board, mid-chew on a delicious mouthful of food, where there is always an onion in some state of disrepair — hopefully a juicy salad onion. I’ll chew a piece into my mouthful to enjoy the raw onion’s sharp, sweet and crunchy flavors.

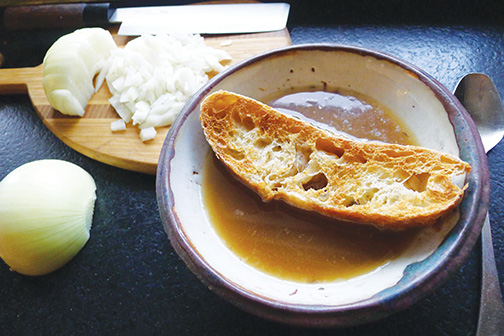

Legend has it French onion soup was invented in a hunting cabin, by the king, of course, when he discovered the cupboard bare of everything but onions and bread. Nobody should be surprised when an onion carries the day. Especially an onion cooked for a very long time.

Recently, in the kitchen of the old chef who taught me how to cut an onion, I watched him prepare an eggplant and tomato recipe into which onions would disappear. Forgotten but not gone, those onions would hold together the flavor with an unseen force more likely to be missed than appreciated.

I asked the chef: “If you were stranded on a desert island, and could only have one vegetable …”

“I would take the onion,” he said gravely, before I could finish.

French onion soup

2 pounds peeled yellow onions, ends removed and sliced from tip to tip

1 stick butter

1 bottle white wine

2 bay leaves

1 gallon stock of your choice

1 tablespoon thyme or herbs de Provence

A crusty white sourdough

Minced onion, as a garnish

Bake the onions at 300 on a cookie sheet, flat side down in butter

Add a half-cup of wine every hour. When the onions begin to melt, use a spatula or wooden spoon to press down and smear apart the layers.

After about three hours, when they are deliciously sweet and browned but not burned, transfer the onions and all pan juices to a pot of stock. Add bay leaves and herbs and the rest of the wine and simmer for about three hours, seasoning with salt and pepper as it cooks.

At serving time, heat the onion broth under the broiler in personal-sized bowls. Slice the baguette, butter the slices and set aside. When the soup is hot, add the bread, buttered sides up, and broil until they are toasted. Garnish with raw onion.

Serves six and can easily scale up