Fish hatcheries cause massive genetic changes after a single generation

A study by Oregon State University and the Oregon Department of Fisheries and Wildlife has confirmed what observational evidence has long suggested — that there are substantial genetic differences between fish raised in hatcheries and those from the wild.

The research was first published in mid-February in the journal Nature Communications. It showed that the offspring of wild fish and first-generation hatchery fish had more than 700 different genes after a single generation, even among the same species — in this case, steelhead trout.

“A concrete box with 50,000 other fish all crowded together and fed pellet food is clearly a lot different than an open stream,” said Michael Blouin, a professor of integrative biology at Oregon State, in a press release.

Mark Christie, the study’s lead author, said that many of the genetic mutations affected healing ability, disease immunity and metabolism, and that this is probably because fish must adapt quickly to living in those crowded environments, where disease is more rampant and injuries are easier to suffer.

“The large amount of change we observed at the DNA level was really amazing,” Blouin added. “This was a surprising result.”

The next step for researchers is to further investigate the causes of this genetic discrepancy, then to address the problem of the DNA discrepancy itself. Blouin said that it might be possible to change the way hatcheries operate so they produce fish that more closely resemble wild fish on a DNA level, but that is further down the road.

— Tommy Wood

Deep-sea “purple sock” is another species of Xenoturbella

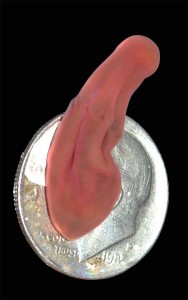

Off the coasts of California and Mexico, scientists have found four new species of deep-sea, worm-like creatures that look similar to empty socks and churros.

Originally discovered in 1949, the genus Xenoturbella has puzzled scientists ever since as they have a single feature: one hole for food to go in and waste to come out.

After finding mollusk DNA inside one, researchers had believed for a short period of time it was a type of mollusk. However, researchers determined rather that the worms like to eat clams and mollusks and are their own genus.

The four new additions range in size from 2.5 centimeters to 20 centimeters and add to a widening conversation about evolution.

“The findings have implications for how we understand animal evolution. By placing Xenoturbella properly in the tree of life we can better understand early animal evolution,” said Greg Rouse, professor of Marine Biology at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the lead author of the paper detailing them, in a press release.

Scientists have classified the worms as evolutionarily simple, meaning they are at the bottom of the evolutionary tree and have always lacked a brain, gills, eyes and reproductive organs. This reflects a change to early belief that the species had evolved to lose features.

Scientists chanced upon them when trolling whale carcasses using remotely operated vehicles.

“I have a feeling this is the beginning of a lot more discoveries of these animals around the world,” Rouse said.

— Alexandria Kade