Trees are sanctuaries. Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them, can learn the truth. They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life. So the tree rustles in the evening, when we stand uneasy before our own childish thoughts: Trees have long thoughts, long-breathing and restful, just as they have longer lives than ours. They are wiser than we are, as long as we do not listen to them. But when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy. Whoever has learned how to listen to trees no longer wants to be a tree. He wants to be nothing except what he is. That is home. That is happiness.”

— Hermann Hesse

From where I now sit typing, I’m looking out on a landscaped row of lodgepole pines punctuated by a volunteer cottonwood. Cottonwoods in the semi-arid prairie always indicate water and this one is no different. Twenty feet from our irrigation ditch, it drinks from the same well we do, and in that way the tree is part of our family and I love it as such.

My dog and I spend many hours sitting under its branches, glad to spend a leisurely moment in such good company. Over the years, I’ve learned to just sit and listen and enjoy what comes, but the other day I found myself talking to it, as if it were an old friend. I felt compelled to tell it a story about the time I went looking for the tallest tree in the world, a giant redwood hidden in the dense temperate rainforest of northern California.

Like all things larger than life, I found out about the tree as if it were a rumor, from a friend-of-a-friend who’d read about it in a book, Richard Preston’s The Wild Trees. He told me about what he’d read, about a small but dedicated group of scientists and explorers who researched the coastal redwoods. This band of men, inspired by the grandiosity and mystery of the forest, worked to unlock its secrets, but also ultimately to revel in its wonder.

The tallest tree in the world was found in 2006 by two of these men, Chris Atkins and Michael Taylor, a pair best described by how deeply and sincerely they love the redwood forest. Many speak of them as explorers, as those who “discovered” the world’s superlative trees, but it’s doubtful they see themselves or their accomplishments that way. The few articles and books about them suggest they would reject any ethic asserting man’s dominion over the natural world. In naming the trees they identified, they weren’t claiming them so much as they were offering titles of respect, reminders of the humility of their quest.

The name they reserved for the tallest tree, Hyperion, was that of one of the 12 Titan children of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (sky) in Greek mythology. Hyperion was the name of the sun god or high one, the first to understand, by mere attention and observation, the movement of the sun, moon and stars. Gaining this comprehension was his defining rite of passage, from seeker of the heavenly bodies to their father, their guide and protector.

I like to imagine Atkins and Taylor similarly, standing at the foot of the newly named Hyperion, looking up toward a crown so high it eventually disappeared into the sky, mingling with what they could only imagine must be heaven. Like new fathers, they offered a feeble promise to protect it from the very world that felled so many of its family. But in their gesture of love and admiration, naming and announcing Hyperion to the world, they unknowingly condemned it, as curious adventurers around the world took their cue and set out to find it for themselves.

People like me: A Colorado girl raised half in the mountains and half on the plains, so intoxicated by the dream-like story of Hyperion that I eagerly borrowed it as my North Star. Deep down, I knew the quest was not authentically mine, but at 30 years old I was restlessly awaiting the call to my hero’s journey and this was close enough. Or people like my friend-of-a-friend, the one who first told me Hyperion’s story, a New Yorker who grew up in the city’s curated landscapes of concrete, steel and bombastic ambition. There was something about the tree’s slow and deliberate rise to 386 feet that stirred a sense of reverence in him. He longed to find it and to learn from its 600 years of life.

Naively, I said we should try to find Hyperion. He laughed dismissively and told me it would be harder than I thought — in an effort to protect the tree, its location was kept a closely guarded secret. Maybe so, I said, but most people I know can’t help themselves. The thing with secrets is that we keep them so that someday we can admit our most important inner truths, confess them and be rewarded for sharing a part of our deepest selves.

It wasn’t that I doubted the good intentions of the original seekers. Au contraire, I admired their work ethic, that of professionals heeding a noble calling. But inevitably, when we put our being totally into our work, we want a little to spill out, too, to leave a little mark that we had been there, done that and that our lives were richer for it. As much as I knew it would be hard, not only to find the location of the tree but to identify it from one of thousands in a forest, I also knew that people would leave their mark.

Even so, if we had looked for the tree 10 years ago, the search would have more closely resembled Atkins’s and Taylor’s, an old-fashioned adventure, taken step-by-step, bushwhacking into the dense unknown forest. But in the modern world the journey was all but won or lost on the internet. And on the internet, secrets certainly aren’t safe. In a couple of months of casual research, my partner and I gained an encyclopedic knowledge of the trees and found enough intel to confidently put an X on the map. As soon as the ink dried on the paper, we packed our bags and headed for the fabled forest.

Before ever stepping foot in California, we thought we knew a lot. Like, even at 600 years, Hyperion is relatively young for a redwood — trees that can live to be 2,000 years old. Even so it has outlived our country and the doctrine of manifest destiny that justified the endless expansion of the American frontier. I once asked my friend if he’d ever visited the Statue of Liberty, a fixed part of his seascape vista and a 305 foot tall symbol of the human quest for freedom. He hadn’t, because it never called to him, he said, not like Hyperion did.

Born an offshoot of another tree, Hyperion grew on its steep hillside, patiently drinking from nearby rivers until it was tall enough to drink from the sky, its needles lapping at clouds carried in by coastal breezes. Like all redwoods, its roots are sensitive and shallow, but protected from forest ailments and critters by a thick layer of ferns and mosses. Hyperion’s most significant defense against people was accidental — that steep hillside it called home made it difficult to get to, difficult to cut down.

Luckily, for most of Hyperion’s life that last line of defense didn’t really matter, as the only people around were small groups of native American coastal tribes, like the Yoruk, who still revere the powerful trees. Their traditional stories teach that the redwoods are sacred living beings; useful, sure, but respected as guardians over their sacred places. Soon enough, ideas of holiness were muted by the buzz of saws when non-native settlers came to the area and started logging in the mid-1800s. The trees seemed an inexhaustible cache of lumber and fueled the growth of a massive industry. Today, less than 5 percent of the old-growth redwoods remain, including Hyperion.

Ironically, it is the busted and dilapidated mining towns that now serve as gateways to the redwood forest, lingering reminders of the delicate balance between humans and the natural world. And it wasn’t until we arrived in one such town, Orick, that I truly grasped the stakes of our two-person expedition. Up until this point, we had been seeking the frontiers of our own potential, but we hadn’t yet admitted or accepted that in stepping into the forest we too were affecting it, we too were inextricably linked to its demise. Suddenly our quest seemed too casual, and as such, unjustified. Who were we to bother this tree? And yet we continued on.

It was in Orick that we got the first sign of our impending success. We stopped at the National Park station to get our permits when a friendly ranger offered to introduce us to the terrain, unfolding a map and highlighting various attractions — scenic vistas, popular trails and then, in a gesture as grandiose as it was banal, he plunked his finger down on the coordinates we had identified as Hyperion. “And this,” he said, casually as if rambling off items on a grocery list, “this is where the tallest tree in the world is.” My partner and I exchanged a wayward glance but held our tongues. Humans just can’t help themselves, I thought.

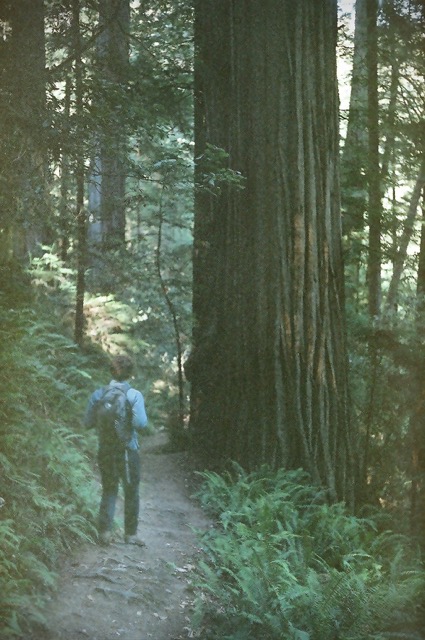

Crossing the threshold into the forest, the deficiencies of learning about the world through the internet were immediately self-evident. We arrived in August, the height of the dry season, and the vibrant reds and greens I had seen in pictures were hidden in thick layers of dust. In my dreams I imagined the forest to smell like damp earth, but a wildfire that raged just a few miles to the south filled the air with an oppressive smoke. I thought we’d feel alone, but we were one of dozens of cars on the road, trying to squeeze our way into crowded parking lots so we could get on the trails.

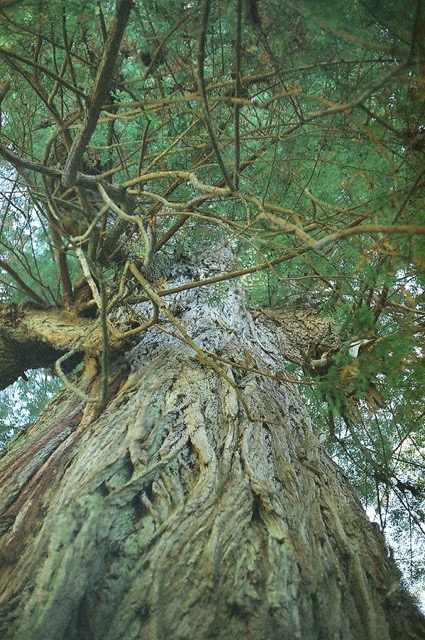

To be among the redwoods is a disorienting experience. The massive trunks outsize one’s largest expectations, and hundreds of feet above human heads tree crowns sway in winds that can only be felt at the height of the troposphere. Absorbing our surroundings, we walked mostly in silence, slowly and deliberately.

Maybe it was the light trickling through the trees as it would through a stained glass window, or the creaking of trunks like church bells, but in the middle of the forest it occurred to me our souls must be made of wood. How else could it resonate so deeply with the forest?

Suddenly and totally, my ambition seemed naked and misplaced. To seek the tallest tree in the forest was a fool’s errand and I most definitely the fool. Having come all this way to look for one tall tree was an act of pride. Now that I was here it seemed all there was to do was surrender to the simple act of being there.

Alas, it would have been even more foolish not to continue, to halt our pursuit and leave the tree in what was at best an imagined peace. I knew we must continue on toward Hyperion because we had crossed the point where we could take it back, remove man’s influence from nature. The thing to do was to finish, to confront our incessantly dominant natures, to stare them in the eye and admit our aggression in hopes of reconciliation.

We took our time but, faithfully, we followed our course until we came across a neon pink metal spike sticking like the sorest of thumbs out of the otherwise pristine forest floor, clearly marking a short and well-worn trail up a steep slope ending at the base of a mammoth tree. Hyperion.

It was nothing but godly in its stature but, like all immortal Greek gods, marked with signs of its vulnerability. The ground around the tree was barren, paths worn around the circumference of its wide trunk, ferns and vegetation dying if not dead, moss rubbed off all nearby surfaces. The rich, red bark of the tree was peeling off, clearly the work of restless human hands, anxious to reach out and touch the tree they sought.

We walked a little further up and sat down, knowing that we were part of the destruction, one of the many hammer strikes that drove that damn pink stake into the ground. I knew then that I didn’t deserve to sit in its shade and wipe sweat from my brow, but I also knew it was inevitable. I knew because sitting there under the mighty tree, Hyperion spoke to me about life and more remarkably, I was humble enough to actually listen.

Trees are people and forests are humanity, it said. Our destinies are intertwined. You are doomed to love me and I am destined to let you, until our dying day.

In the days that followed we made our way out of the redwoods and back down the coast to San Francisco. When we became overwhelmed by the magnanimity of our experience, we didn’t know what else to do but hold hands.

And now, back in Colorado, I make a point to spend time with trees, although noticeably smaller and more tortured in their search for water and life. But you know what? It’s enough just to sit below an ordinary tree, to take it up on its standing offer for shade and company.

Although there has been no formal press release, it is widely rumored in online tree-seeking communities that trees taller than Hyperion have since been discovered, but kept under wraps in an effort for protection. Whether or not there is truth to these rumors, it is worth noting that the heights of trees are always in flux. Nothing is ever the same.