The illegal grow operations John Nores with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Marijuana Enforcement Team would break up were all different. Sometimes the cartel members would be heavily armed, and the fish and game warden would have to exchange gunfire with the growers to subdue them (Weed Between the Lines, “Fighting the dark side of cannabis,” Dec. 23, 2021). Sometimes they would throw their hands up in surrender as soon as they saw the officers, decked out in special-ops gear, holding loaded AR-15s. Other times, the grows would be abandoned by the time the CDFW enforcement team got there.

But the one thing they all had in common, according to Nores, was the aftermath. The environmental destruction was horrific. There would be tons of trash, human waste, animal traps, and, worst of all, remnants of toxic pesticides, many of which had been banned by the Environmental Protection Agency for decades.

“You look at the toxicity of that type of product and know that it’s being used at every grow site that these cartel growers have and the environmental impacts are so pervasive … it’s affecting our wildlife and our wetlands and waterways at their most sensitive spots: the source,” Nores, who founded the CDFW Marijuana Enforcement Team, says. “It’s really not a cannabis issue. It’s an environmental crime.”

An environmental crime Ivan Medel didn’t think scientists were exploring enough. One that, as an assistant ecologist with the Integral Ecology Research Center (IERC), he was well positioned and motivated to shed some light on.

“These sites are all over the place throughout the western U.S., in deserts, on top of mountains and everywhere in between,” Medel says. “And we know pesticides are being used or applied in large volumes and in high concentrations.”

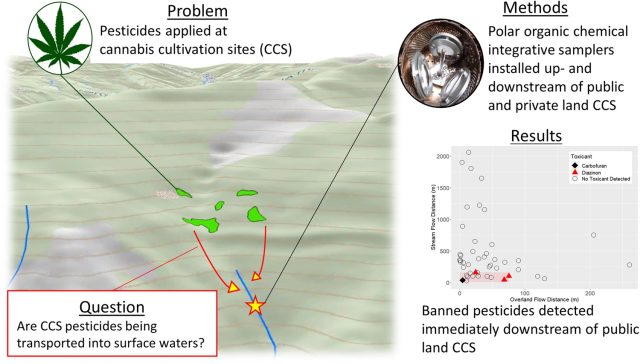

So he and several other researchers set out to determine how far those pesticides might be traveling, and how long they stay in the environment. They used polar organic chemical integrative samplers to monitor the contamination both upstream and downstream of the kinds of illegal grow operations the CDFW enforcement team breaks up all the time.

“These are not your mom-and-pop private grow sites,” Medel says, these are illegal public land cannabis cultivation complexes.

When Medel and his team embarked on this study, he says their expectation was that the contamination was not being carried off site. He says they had been hopeful that it was a highly localized issue that wasn’t affecting tributaries and downstream watersheds.

But that was not what they discovered. According to their paper, published in the Water Quality Research Journal, “We confirmed that trespass cannabis cultivation complexes are water pollution point sources for both organophosphate and carbamate pesticides.”

Medel says the contamination was present for as far as 11 miles downstream from the sources for a full year after the last application.

“It was very, very surprising,” he says.

And it’s very disheartening. There are hundreds of these grows on public lands just in California, according to Nores; 80% of the illegal cannabis sold in the U.S. is grown on California land that belongs to American citizens — in national forests, national monuments, state parks, and throughout BLM land.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, in the five-state Rocky Mountain Region there were 71,000 plants eradicated from public land in 2017. That’s 26,000 more than they eradicated in 2016, and 68,000 more than they eradicated in 2015.

In 2019, just in Fremont County, Colorado, officers seized 4,200 cannabis plants they found growing in San Isabel National Forest. The same year, in the White River National Forest near Carbondale, Colorado, another 2,700 plants were discovered and destroyed.

And as in California, most of those sites are using highly toxic pesticides that leached into waterways, killing aquatic life, and damaging creeks and streams.

Medel hopes the information their study exposed can be useful for land managers, and will make a difference across the state, and the western U.S. He says, now that they’ve established the contamination is not a localized issue, the next step for them is to examine the extent to which it’s affecting the ecology of our watersheds.

We know it’s out there, he says, now the question is: How bad is it?

While Medel continues down that path of research, the CDFW Marijuana Enforcement Team will continue to raid and break up illegal grow operations responsible for contamination. And, importantly, they will continue to clean them up. Nores says environmental remediation is the most important aspect of their job.

However, this contamination wouldn’t be such a pervasive issue on public lands at all if it weren’t for the federal prohibition of cannabis. If it weren’t for cannabis’ status as a schedule I narcotic, the black market demand for it would disappear — along with most of these trespass grow sites.

Nores sums the problem up succinctly.

“If cherry tomatoes were on the black market for $4,000 a pound, and it was illegal to grow them and sell them, we’d be having gunfights over cherry tomatoes,” he says.