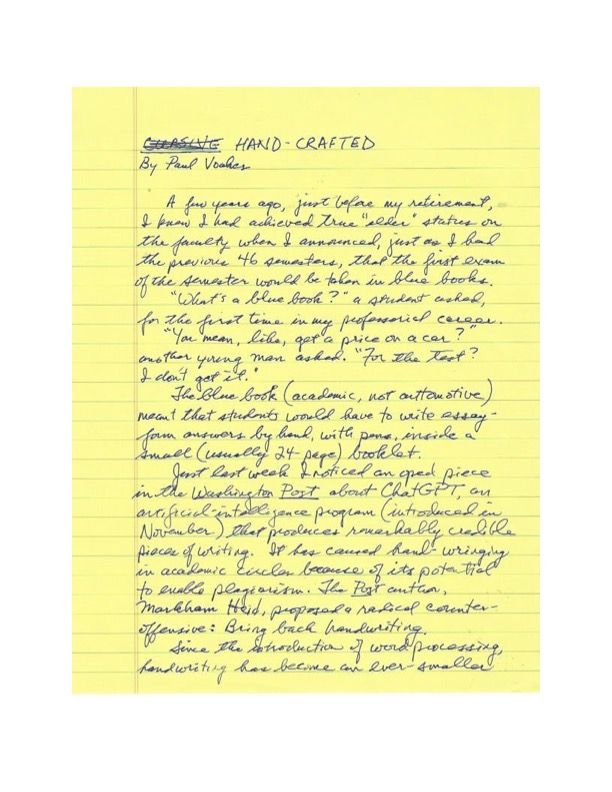

A few years ago, just before my retirement, I knew I had achieved true “elder” status on the faculty when I announced, just as I had the previous 46 semesters, that the first exam of the semester would be conducted in blue books.

“What’s a blue book?” a student asked, for the first time in my professional career.

“You mean like, get a price on a car?” another young man asked. “For the test? I don’t get it.”

The blue book (academic, not automotive) meant that students would have to create essay-form answers by hand, with pens, inside a small (usually 24-page) booklet.

Just last week I noticed an op-ed piece in the Washington Post about ChatGPT, an artificial-intelligence program (introduced in November) that can produce remarkably credible pieces of writing. It has caused a good deal of hand-wringing in academic circles, because of its potential to enable plagiarism. The Post author, Markham Heid, proposed a radical counteroffensive: Bring back handwriting.

Since the introduction of word processing programs, handwriting has become an ever-smaller part of daily life for nearly every adult in the United States. We put pen to paper to send the occasional greeting card, perhaps to write a personal check, maybe a shopping list. (But even most shoppers at the supermarket, I’ve noticed, now consult their phones.) The benefits of writing with computers are plain. It helps the environment by saving millions of reams of paper each day. And using a word processor is simply more efficient. A keyboarding writer can compose an essay, even making 159 revisions, in a small fraction of the time it would take to write the same essay by hand. And as some of us recall from our school days, misspelling a single word often meant tearing up the sheet and starting again.

Is there value in reading and writing cursive?

The education establishment seems to have little appetite for handwriting instruction. Twelve years ago, handwriting was dropped from the nation’s Common Core for grades K-12. Since then, I’m pleased to see, nearly half of the states — but not Colorado — have reinstated the mandate.

My preference for blue book exams goes to the heart of why I still believe in handwriting. Handwriting compels the writer to think through to an entire sentence, and often to an entire paragraph, before writing the first word. Digitized writing, by contrast, encourages the writer to dump words onto the screen and begin a process of cutting, pasting, deleting and inserting until the verbiage starts to resemble expository writing. When the subject is law or ethics (the courses in which I required blue book exams), crafting a cogent argument before starting to write is a commendable skill. And without a laptop for the exam, all cheating schemes become low-tech and highly risky.

I dug a little deeper and found a small but growing body of research on the effects of handwriting versus word-processing. Cognitive scientists have found that handwriting, while exasperating for most young students, demands a degree of small-motor and hand-eye coordination that is rarely found in the classroom, yet useful later in life. More surprising to me were the findings that handwriting is positively correlated with better processing of concepts, more creation of original work, and better accuracy in comprehending foreign languages.

I would add a certain cultural value. Handwriting is part of each person’s identity. We were taught to copy exact forms for each letter, printing and cursive, but by the time we’re adults we’ve each developed a handwriting style that is uniquely our own. Whenever I would receive a letter or note from a parent or sibling — back when we would write to each other by hand — I knew exactly who had written it after reading the first three words. We each had a signature, for writing checks, or signing memos or receipts. Nowadays, of course, a scribble qualifies as a signature. Do we really want to lose this part of our identity?

Handwriting was a common means of written communication for centuries, before the advent of word processing. Will our grandchildren even be able to read handwritten historical documents from the 19th and 20th centuries? Will they be able to read letters written by their grandparents? A friend of mine recently read a trove of love letters — nearly 700 of them — exchanged between her grandparents from 1900 to 1909. She organized the letters into a loving, historically fascinating book, which was published just last month. Every one of those letters was handwritten. What if my friend had lacked the ability to read cursive?

I’ll continue to write by hand, but, I must concede, only when the situation seems appropriate. After all, this essay took me hours to write in cursive — and I wrote it out only after I’d typed my rough draft on a laptop!

Professor Emeritus and Founding Department Chair Paul Voakes has taught journalism at CU since 2003.

This opinion column does not necessarily reflect the views of Boulder Weekly.