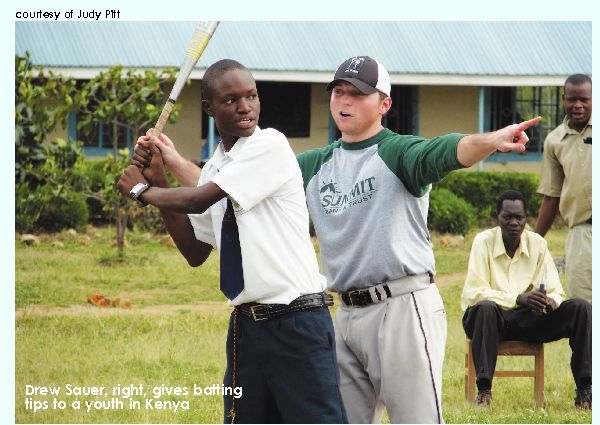

It wasn’t about religion, although the trip was organized by a missionary. And it wasn’t really about baseball, although most of the luggage was packed with sports equipment. But the trip to Africa that local residents Jim Cederberg, 55, and Drew Sauer, 28, went on last winter has them committed to returning regularly, bats, balls and gloves in hand.

And yes, they go to teach baseball.

But they say what they bring back is what matters.

When a Boulder missionary approached Sauer at the bank where he worked and asked him to consider coming with her on a mission trip to Kenya in February, his response was that he’s not all that into Bibles. But she knew he was into baseball, and the children she was working with were desperate for recreational outlets, so she asked if he would consider coming to teach baseball to the kids. Sauer had gotten to know Cederberg, a local attorney, at the bank and had played baseball with him, and he knew Cederberg had been to Africa before. So Sauer got Cederberg involved.

Cederberg had coached his own children, now in their 20s and 30s, through baseball leagues, and Sauer played baseball for Concordia University but had never coached sport.

On Feb. 18, they flew to Nairobi, Kenya, joining a group of missionaries for 10 days of visiting orphanages and schools in rural areas. They arrived with eight duffle bags stuffed with donated baseball gear, including 100 baseball gloves.

The kids went from treating the pair as outsiders to clumping around them at the end of the game, asking questions like “What does snow look like?” and “Why are we dying of AIDS while Americans are not?” “Once you get over there, the baseball definitely becomes secondary,” Sauer says.

Their guide was one of the pastors who managed one of the orphanages full of children whose parents had died in the AIDS epidemic.

Once, they were stopped by a woman whose children had been hit by a car. The pastor drove her to the hospital to see her children, and then drove her and her injured children to a bigger hospital about 25 miles away, with Sauer and Cederberg riding along.

“When we first got there, they took us to this church compound thing, and this one pastor comes up to us and he looks me right in the eye and he says, ‘You do not accept the lord Jesus Christ as your savior, do you?’ and I’m thinking, ‘Oh God, 10 days of this?’ And it turns out, he was our guide,” Cederberg says. “And at the end of the time, we were leaving … and he hugged us and I mean, it was an embrace, and he said, ‘I love you.’ So we went from being about religion and what you believe, to being about we’re human beings. We all share this experience.”

While missionaries do great work, he says, there was a sense they just didn’t get that idea of shared human experience.

“Their religion got in the way of them really understanding the human connection. It was almost like they were selling a product, and that got in the way of them really understanding the connection,” Sauer says. “So for us, baseball got us closer to these people.”

“We went over there with the attitude that we’re going to share the baseball, but we’re not really here to tell them something. We’re here to learn. And I was kind of harping on Drew on that on the way over. We’re like a sponge — and we were,” Cederberg says.

There’s just something about the game, he says. He talks about the smiles on the faces of girls who, in a culture where they otherwise see persistent inequality, are taught to throw and catch a ball just like the boys.

At one orphanage, a little girl who had lost part of her hand in a fire hung back from the group of kids who were eager to play. Cederberg showed her how to slide the glove on and use it to catch a ball with just the fingers she had left.

When asked what they want to be when they grow up, many of the kids said they want to be pilots, Cederberg says. “Pilot,” he discovered, is the word they use for the guy who drove him around.

It’s confusing, he says, to come back from a place like Africa and look at spending money on something like remodeling the kitchen.

Since returning, Cederberg has continued to send $600 a month to one of the pastors — a man whose house has never been built beyond a few feet of brick outline, who cares for a group of 30 orphans who pray in a windowless church, sleep in a metal, barn-like bunkhouse, eat food cooked on charcoal stones in a stick-and-mud kitchen, and consider a good meal chopped greens and cornmeal mush. The money he sends pays for their food for a month.

Anywhere Cederberg and Sauer went, other pastors approached them and asked them to come teach baseball at their orphanage, to come play with kids who had never seen a white person before.

“There’s no way we can walk away from this,” Cederberg says. “It was obvious in the 10 days we were there we’d just barely started to scratch the surface.”

They made the decision on the way back to America to start their foundation, 42-22 Humanity Through Baseball, which was just granted 501(c)3 nonprofit status.

In December, they will return to Kenya with two other men interested in teaching baseball. They’ve scheduled themselves to teach at two or three schools a day, and will stay in the same guesthouse they did on their last trip, revisiting some of the same orphanages and schools, and then visiting a few new ones. This time, they will get to the Masai Mara, an area where the people are known for traditionalism, like the Amish in America.

“The next trip we’re going to learn more about how things work, learn more ways to do stuff with orphanages,” Cederberg says. “It doesn’t have to all be baseball.”

They’re doing some fundraising now, sending letters and e-mails to family, friends and business associates. They’ve collected bats and shirts. What they most want are used gloves, already broken in. And they want people who are interested in coming on this trip or ones in the future. After watching the way women struggle to achieve equality — and how playing baseball with the boys could help level the field — they’re hoping to find women who might set an example for the girls there.

Cederberg is taking donations at his law office, 75 Manhattan Dr., #203 Boulder, as is Summit Bank & Trust, 2002 E Coalton Rd., Broomfield. Additional information is available at www.42-22.org.

Respond: [email protected]