When Katie Selvage stepped into an unassuming Santa Fe gallery for inspiration to take home to her own art space in Boulder, she didn’t know she’d be leaving with a trunkful of rock ’n’ roll history in tow.

Selvage had been exploring the southwestern culture hub with her husband Patrick, vinyl buyer at Paradise Found Records on Pearl Street, to gather ideas she might replicate as owner and operator of IMA on North Broadway. But things took an unexpected turn for the music-obsessed couple when they walked through the doors of Edition ONE, a sleek contemporary gallery tucked away on the New Mexico city’s famed Canyon Road.

“He took off for one room, I went to another room, and we met up in the middle,” she recalls with fresh enthusiasm. “I was like, ‘You’ve got to see this,’ and he’s like, ‘No, you’ve got to see this.’”

What had so stirred the Selvages was a smattering of works by rock photographers Lisa Law and David Michael Kennedy. From the former’s candid portraits of legends like Janis Joplin and Bob Dylan to the latter’s iconic album covers for Bruce Springsteen, Muddy Waters and more, the era-defining artists are together responsible for some of the most memorable images in music history — and it was all right there on the wall, staring back at them.

Moved by it all, Selvage and her husband struck up a conversation with gallery owner Pilar Law, a photographer in her own right who so happened to be the daughter of the famous artist sharing her last name. After learning about Selvage’s own art space in Boulder and her husband’s ties to the music scene, the idea of hosting an exhibition of these images here on the Front Range began to take shape.

“To see how they were able to capture these musicians, these vessels of the divine, I was just in awe — starstruck,” Selvage says. “And I was like, ‘OK, this is it. I’m doing it. We need this here in Boulder.’”

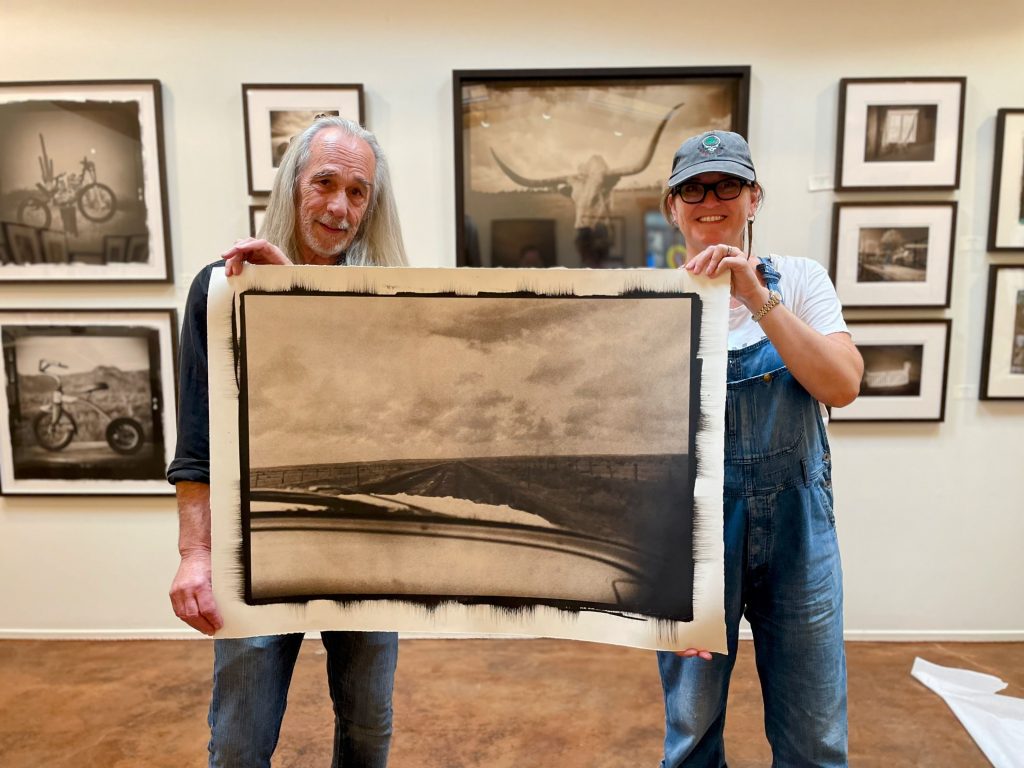

After spending more time with Pilar and visiting Kennedy at his remote studio in El Rito about an hour north of town, the Boulderites drove back to the People’s Republic with a carload of images that would become the upcoming IMA exhibition of works by the celebrated photographers. Running through Dec. 16, the show marks a new gear for Selvage’s NoBo gallery space and represents the culmination of her mission to breathe new life into the city’s visual art scene.

“I want to bring something that really inspires and shakes things up … Boulder is ready for something more than landscapes and pastels,” she says. “I wanted to bring something a little bit more provocative, a little bit more raw. I felt like our gentle hippie sensibilities were ready for it.”

Vibe shift

When it comes to shaping those “hippie sensibilities” in the popular imagination, few figures loom as large as Lisa Law. In addition to the big-time musicians who found themselves immortalized in her lens, she also captured key figures and events defining ’60s counterculture, like psychonaut Timothy Leary, author Ken Kesey and the earliest moments of Woodstock. Regardless of her subject, each image shares a disarming intimacy that draws in the viewer and makes them party to the historic moment caught in the frame.

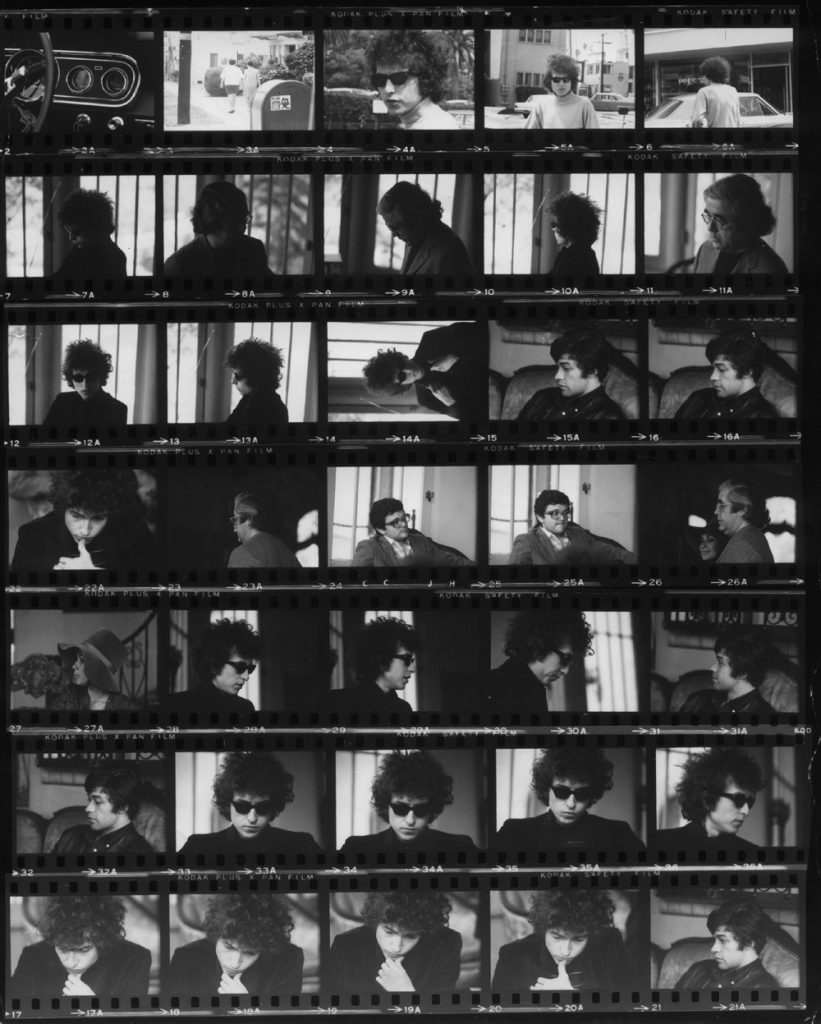

“I’m really fast on the trigger. And what I’m trying to capture is the essence of that person at that moment. I don’t want them to pose,” Law says. “Back then I was just documenting what I saw. So when Bob Dylan was standing around talking to his manager [Albert Grossman] in the solarium at The Castle, I just took pictures.”

Here Law is referring to the four-story Los Feliz mansion where she lived for a time with her late former husband Tom Law, then road manager for the folk revival trio Peter, Paul and Mary. She photographed the visiting musicians and artists who cycled through the lavish Hollywood digs, producing some of the most iconic images of the era’s biggest rock stars, artists and thinkers.

But when it came to her outsized role at Woodstock, Law did much more than document. In addition to helping with medical tents and security, she requested $3,000 from organizers to buy ingredients — rolled oats, bulgar wheat, honey, soy sauce, dried apricots, wheat germ and almonds — to make muesli, which she and other volunteers passed out in Dixie cups to the hungry hippies in attendance. It turned out to be a lifeline in more ways than one.

“The governor of New York was trying to make it a disaster area, and we kept saying: ‘No, we’re taking care of everybody. We’re feeding everybody. Everybody’s enjoying the music,’” Law says. “If you call in the National Guard, it changes the vibe.”

Law might have made the wheels of history move during pivotal moments like Woodstock, but her work found its truest expression when she stepped back and observed. Asked about the stories behind those moments of quiet capture, she doesn’t hold back on the salacious details.

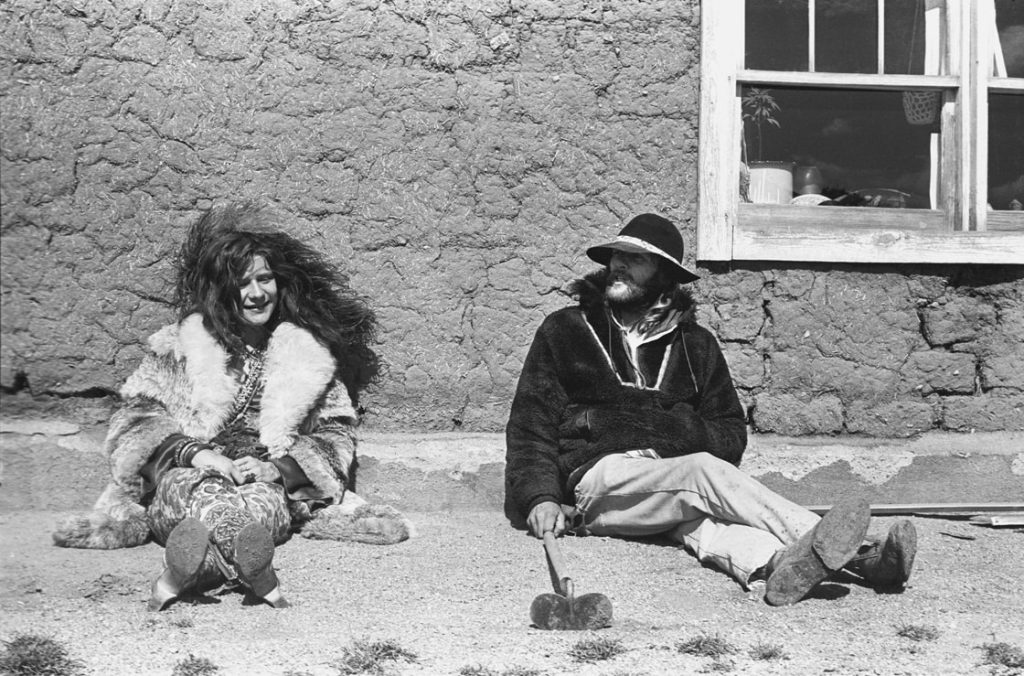

“I shot Janis Joplin in San Francisco, and she came out to my house in New Mexico. She says, ‘I’m looking for a mountain man. I’m tired of these city men.’ And I said, ‘I got one … I’ll put you together,’” the 80-year-old artist recalls. “She made love to him all night long in his cabin, came back down and sat against the adobe wall of my house with Tommy Masters, who became Bob Dylan’s driver for 15 years. I took this picture, which is now one of the most famous pictures of Janis Joplin. It’s up at the governor’s office. It’s her after she got laid by the mountain man.”

‘Everybody loves them and nobody knows them’

David Michael Kennedy used to tell a more innocent story about what first sparked his interest in photography. But these days, he’ll give it to you straight: The calling came during a teenage acid trip with his buddies on Long Island.

“Everybody else had gone to sleep. It was an early spring morning, and I was still tripping. So I picked up a Nikon camera that was sitting on the mantel … I took it outside and started looking through it — focusing on the dew drops, the leaves and the light spectrum coming through,” he says. “I just fell in love with being able to isolate time and space to sort of say, ‘This is important to me.’ And I decided this is what I want to do with the rest of my life. I never looked back.”

From there, Kennedy eventually made his way to the advertising department at CBS Records, where the twentysomething got his first taste for music photography as the peace-and-love era gave way to the grime and grit of the ’70s.

“I really wanted to do album covers, because that’s where you get to work with the artists — and it’s a lot cooler than shooting those stupid ads,” he says. “But the album cover department and the advertising department hated each other. So the fact that I was working for the advertising department meant it was going to be almost impossible to get into the album cover department.”

So he pitched a photo essay about the industry’s leading art directors to a trade magazine, with the hopes of demonstrating his chops to the people who could help him transition to a more creative professional path. It worked, and within a few short months, the majority of Kennedy’s business was shooting album covers.

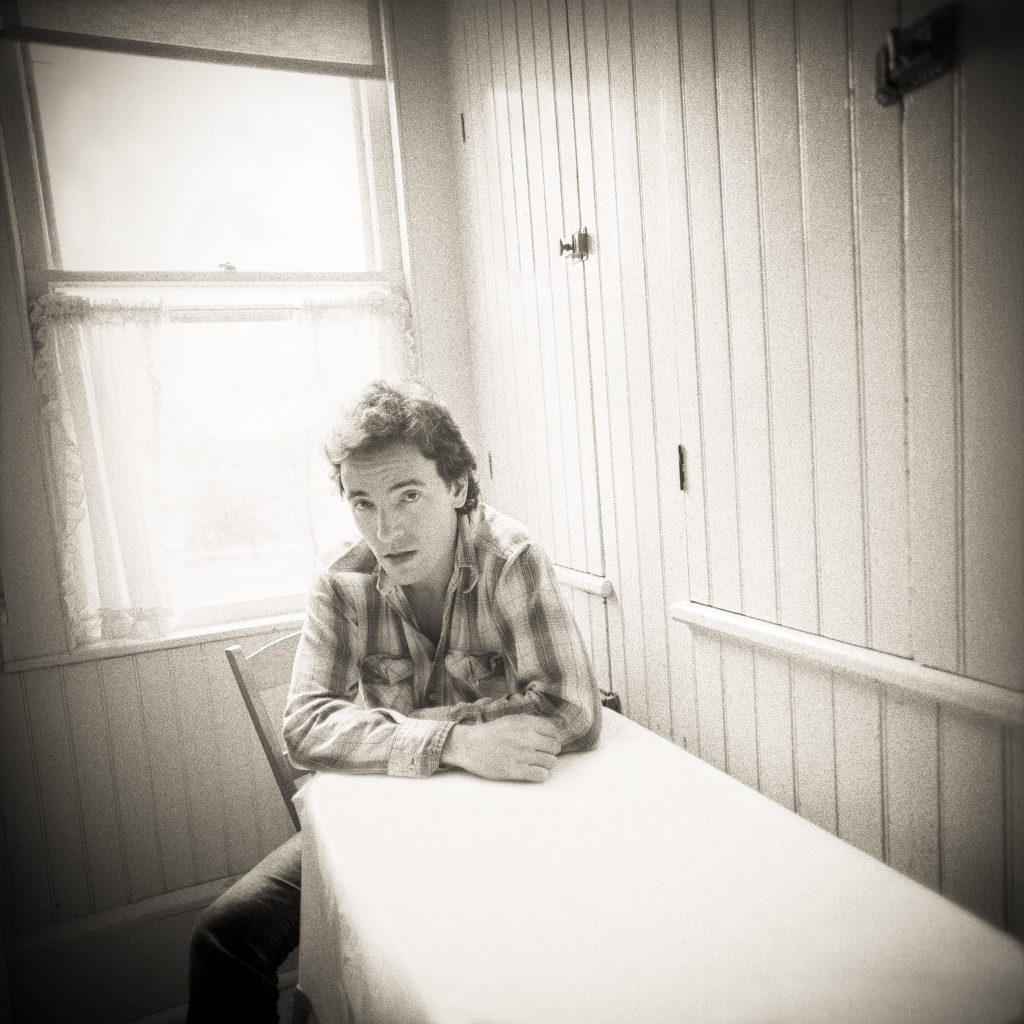

Soon the emerging photographer found himself working with some of the leading artists of the time. That included a pivotal job with Bruce Springsteen, who put one of Kennedy’s landscapes on the cover of his 1982 masterpiece Nebraska and hired him to take promotional portraits for the record. But when the pair first met up, it wasn’t clear whether the relationship would be a fruitful one.

“I could feel there was a wall between us. A lot of these musicians — and famous people in general — are really guarded, because everybody loves them and nobody knows them,” the 73-year-old Kennedy recalls. “And that’s got to be a very strange place to be: Every time you meet someone, I would think it’s sort of like, ‘Well, what do they want from me? They’re being really nice to me, but they really don’t know who I am inside. They just know this bullshit persona that’s out there.’”

For this particular icebreaker, Kennedy sat down with the Boss for a private listening session of Nebraska on cassette tape. Kennedy had already fallen in love with the record, but the close quarters gave him the opportunity to take a big risk that would ultimately land him the gig.

“I said to him, ‘Bruce, I have to be honest with you: I’ve never really been a fan of your music. But this album just touches my soul and my heart, and I would be so honored to be a part of this project,’” he recalls. “And as soon as I said that, the wall just disappeared.”

Kennedy would go on to shoot more of the era’s most iconic musical figures: Iggy Pop, Debbie Harry, Willie Nelson and countless others. In contrast to Law’s candid glimpses of the greats, his style is a more composed and deliberate capture of the animating essence behind these larger-than-life cultural figures. But if you ask him what makes for a great portrait, he’ll give you an answer that defies the grandeur of the icons refracted in his lens: It’s simply about enjoying the moment with the person on the other end of the camera.

“The most important thing for me is getting the person to relax, feel comfortable and open up a little bit,” he explains. “Before we’d start shooting, I’d say: ‘Look, what’s important today is we have fun. Because if we have fun and make horrible pictures, we can always come back and make more pictures. But if we have a horrible time and we make good pictures, we’ve lost that time. We can never get it back.’”

ON VIEW: Opening reception with David Michael Kennedy and Lisa Law. 6-9 p.m. Friday, Nov. 17, IMA Design Gallery, 4688 Broadway, Boulder. Free