On a cold January day, with temperatures hovering just around freezing, a group of 20 kids, 18 months to five years old, and a handful of their parents gathered for a day of kindergarten in Denver City Park. Bundled in warm, waterproof clothes, no one complained of the cold. After all, they signed up for this: to learn how to be comfortable playing outside, even in inclement weather.

The group circled around Megan Patterson, director of Worldmind Nature Immersion School, reading aloud a story about animal tracking. Just as she began to read about the fox, the faces of the onlookers filled with looks of surprise and awe. One after another, they pointed behind Patterson to a fox that came to sit just out of her reach. She says they stayed like that, the group studying the fox and the fox the group, for a good five minutes until he casually walked into a cluster of shrubs. After he left, the parents stood by as the children tracked the trail that brought the fox into their lesson.

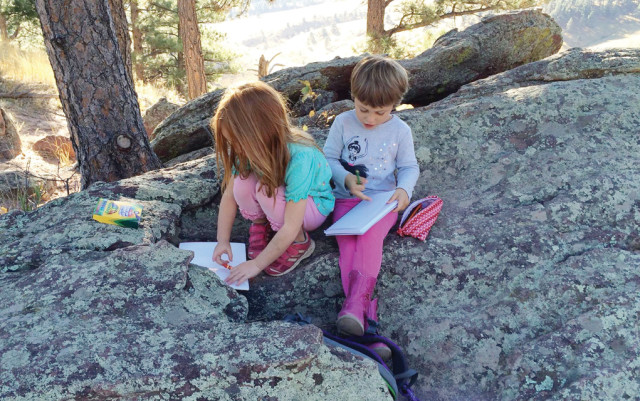

This sort of fortuity happens all the time, Patterson says, but she doesn’t brush it off as coincidence. Worldmind Nature Immersion School is a forest school, founded on the idea that education isn’t about teaching children, but about creating opportunities for them to learn under their own self-direction outdoors. These schools remove the walls from early childhood education, trading them in for trees, rocks and streams.

A report published by the National Wildlife Federation in 2010 states that children in the U.S. are only spending about four to seven minutes a day in unstructured outdoor play. Patterson and other forest educators worry about the negative health effects of this shift indoors, and they hope forest programs can turn the tide by increasing the amount of time children spend outdoors.

But as forest kindergartens grow in popularity around the world, such schools in the U.S. are struggling to get off the ground. Despite a strong grassroots network of educators and parents seeking nature-based early childhood education, government lags behind. In large part, this is due to regulatory issues preventing forest schools from getting licenses.

Patterson’s school isn’t eligible for a license because it doesn’t operate with an indoor facility. Without the option to license, many programs are forced to operate around the system. For Patterson, this means requiring parents to accompany their children for the duration of each three-hour session.

Arguably one of the most successful forest programs in the U.S., Cedarsong on Vashon Island in Washington, is also unlicensed. The school’s founder and director, Erin Kenny, is considered by forest educators as the mother of the American movement, in part because she offers a teacher training program that has helped to inspire the establishment of more than 80 (mostly unlicensed) forest schools in Washington state alone.

Since Kenny lives on a small island, it is very easy to track the progress of graduates as they go through primary education.

“Teachers report that all of these kids do very well academically because they are the ones whose problem solving and critical thinking have been left in tact,” Kenny says. “Because of the programming, they are also the kids more willing to take risks, to raise their hands and risk being wrong.”

While Kenny’s evidence is anecdotal, she’s beginning to get some research on her side, though much of it comes from the other side of the pond. In 2006, UK-based think tank New Economics Foundation evaluated two forest schools — one in England, one in Wales — and found participants gained confidence, social skills, language development, fine motor skills and longer attention spans.

Here in the States, Kenny is growing increasingly frustrated by the obstacles forest schools face in becoming licensed

“There is a serious disconnect between regulators and educators,” Kenny says. “The movement is happening and people are finding ways around the regulations, but what really needs to happen now is that we have to have some change at the government level. [Regulators] seem to agree that children need more outdoor time and yet they are not allowing for that with all of the onerous regulations and restrictions that are placed on outdoor education preschool programs like forest kindergarten.”

Patterson generally agrees with Kenny and is doing her part to push change, but her first priority is as an educator and business owner. And, as an emergent educator ought to be, she is happy enough to get creative and work around the rules. After all, the regulations exist for a reason — to ensure that young children are safe — but Patterson worries we will insulate our children to the point where we strip away all risk of any kind.

“There is a reason why there are strict childcare licensing regulations,” Patterson says. “They are there to keep kids safe, but I think we have gone to the extreme with them. I mean, everything is regulated and that kind of ties your hands when you want to work with kids.”

As she forges ahead, Patterson is offering a different kind of benefit than she set out to, but she is able to see the positives — and parents are, too. Less than a year after opening for business, her five class offerings around the Front Range are filling up and earning glowing reviews.

“In a way, I am really glad that we switched models,” Patterson says. “The parents themselves haven’t taken the time to explore just one small area where they are hiking and they are beginning to realize the same benefits as the kids. Now they just want to stop and play and care less about getting to a destination.”

Respond: [email protected]