With twice the current population, will there be left any wilderness areas, remote and quiet places, habitat for song birds, water fowl and other wild creatures? Certainly not very much.” — Gaylord Nelson, founder of Earth Day

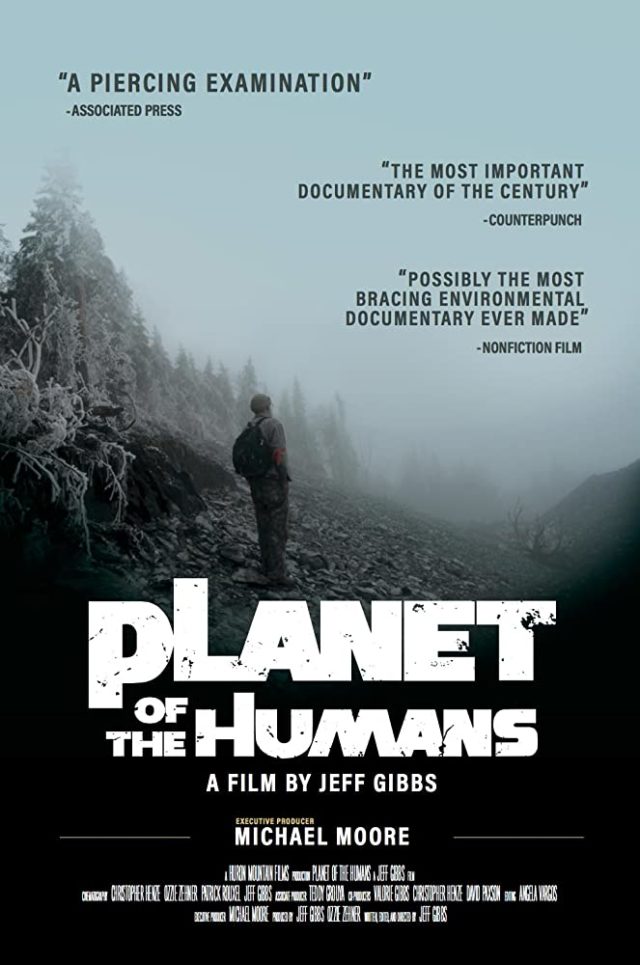

Planet of the Humans — the sweeping and highly controversial film by executive producer Michael Moore and filmmaker Jeff Gibbs — has been viewed 3.4 million times on YouTube as of this writing. That’s great news because the film is one of the most important environmental documentaries of the 21st century so far.

The film goes where no environmental documentary has gone before, deep into criticism of the American environmental movement over the last two decades, a criticism that is long overdue and necessary.

First and foremost, the film’s major premise is that the American environmental movement completely ignores the “elephant in the room” — human population growth. The filmmaker, Jeff Gibbs, as well as other experts interviewed in the film make this point several times:

“Though each of them takes climate change seriously, every expert I talked to wanted to bring my attention to the same underlying problem.” — Jeff Gibbs

“There are too many human beings using too much, too fast.” — Richard Heinberg

“As a global community we have really got to start dealing with the issue of population.” — Steven Churchill

“Population growth continues to be, not the elephant, the herd of elephants in the room.” — Nina Jablonski

There are, in fact, very few environmental groups that even have population programs — the Center for Biological Diversity being a notable exception — while none of the groups highlighted in the film have population programs.

The famous environmentalist and Sierra Club Director, David Brower once said that, “Population is pollution spelled inside out,” but Brower’s successors at the Sierra Club have erased Brower’s population legacy at the Club. Further, no environmental group — as in none — has a program about reducing population growth in the U.S., a country whose rapidly growing populace is among the biggest consumers and polluters in the world.

Second, the film makes a case that the American environmental movement has “sold out” to corporations and polluters due to financial ties and gifts. There is some truth in this premise, but there’s even more truth in the fact that “corporation sell-out” is not the biggest problem, but rather sellout to huge foundation donors and individual donors is more problematic.

As just one of hundreds of examples, the Energy Foundation, based in San Francisco, is headed by former Colorado Governor Bill Ritter, who has long been an outspoken champion and cheerleader for fracked gas as a “mission critical fuel” in the clean energy economy. The Energy Foundation funds almost every organization mentioned in the film, and has deep influence in the American environmental movement including on the leading political-environmental organization, the League of Conservation Voters and its many state affiliates.

Every environmental group has some level of ties to its larger donors’ influences, and the bigger the group, the more often and pronounced the influence. There are paths forward that allow groups to avoid these influences — such as having very strict “mission” and “conflict” policies, and relying on small donors rather than large — but as environmental groups grow in size, these paths are almost always overwhelmed by donor influence.

Third and finally, the film makes a case that renewable energy has an environmental footprint that is often neglected in wholesale support for “clean energy” as the technological solution to climate change. It’s important that this case be made because the implications of building exponentially more wind and solar or biofuels, and more electric cars, are often ignored or greenwashed by environmental groups.

Although much of the film’s footage and argument is now outdated, there’s a section in the middle showing a sequence of images and words with hectic music that hits hard on these important issues. For example, the impacts of mining rare metals, the impacts of lithium mining, and the impacts of all of the other materials used in clean energy and batteries is often ignored.

The film hits on the issue of electric cars, also with outdated information and footage, but this issue is only accelerating now. The environmental footprint of building cars, fueling cars with electricity, and storing that electricity in the car and on the grid is often ignored by environmental groups, especially when the world needs over a billion cars. There’s just too many people wanting too much energy — there’s no way to produce this energy without massive negative environmental impacts.

Planet of the Humans has intense critics, and I highly encourage readers to read and investigate those criticisms. You can google reviews of the film, or take a look at three — by 1) Bill McKibben, 2) Emily Atkin, and 3) Josh Fox. I greatly respect all three of these voices — as well as the many others criticizing the film — and I encourage a broad public dialogue about the film and its criticisms.

My two main criticisms of the film are 1) that it puts too much blame on the American environmental movement and some specific environmental groups. The juggernaut we are fighting against is a thousand times bigger than most of the budgets of the groups combined. Further, the biggest groups with the biggest budgets are the biggest problem, in my opinion, and thus the film lumps “environmentalism” all together when the activities of The Nature Conservancy (which is sometimes called “The Nature Conspiracy” — it has a huge budget, is corporate/market-driven, and arguably very sold out) are very different than 350.org (very small budget, somewhat radical and anti-corporate, and mostly true to its tight mission).

And 2) is the “gotcha” journalism tactic of sticking microphones in eco-celebrities’ faces and asking an adversarial question, and then tightly editing those quotes to achieve a specific gotcha outcome. I happened to be at the climate march in September 2014, and I can personally attest to the right-wing attack journalism that was on display at that particular event. While Mr. Gibbs’ questioning wasn’t exactly “right-wing attack,” it was “adversarial.” I strongly believe that if filmmakers of this stature — Moore and Gibbs — would have given the eco-celebrities the opportunity to have a thoughtful interview, each would’ve done so with a different result.

Despite its faults, I highly recommend Planet of the Humans. Its main premise — that environmental groups are selling “hopium” and have degenerated into corporate-greenwashed advocacy for technological solutions to climate change — is an important beginning for discussion. Second, the film then forces a necessary discussion about what environmentalism needs to become, which is a comprehensive critique and advocacy against human overpopulation, overconsumption and overdevelopment. We need to have a positive aim of creating societies with fewer people, more protected areas and economies that support limited numbers of people comfortably rather than in energy-resource luxury.

Moore and Gibbs released Planet of the Humans on Earth Day, the founder of which, Gaylord Nelson, was a staunch believer that human overpopulation was a key driver of environmental degradation. Since Earth Day 1970, the U.S. population has increased by exactly 60%, from 205 million to 328 million, and is expected to reach 440 million by the year 2065 — which will likely be 440 million high energy consumers and high resource consumers.

The U.S. is a country of humans, on a planet of humans, with no end in sight.

Gary Wockner, Ph.D., is an environmental activist and part-time Boulder resident.

This opinion column does not necessarily reflect the views of Boulder Weekly.