ROSA SABIDO

As I drove west of Durango, Colorado, on Highway 160, the absurdity of it all began to set in, aided by the landscape. I topped a hill and what seemed like the entire West came into view all at once — the horizon so distant and blurred by heat I could only assume it was there. As I continued across the expanse, I saw mostly nothing: a few cows, a home on an acreage here and there, the occasional grisly reminder that some deer are less lucky than others. I wondered aloud why, in all this emptiness, is there not room for one 53-year-old woman named Rosa? But I knew that overcrowding was hardly the issue as I pounded the horn with my fist a few times for good measure — only to startle a post-sitting magpie who had nothing to do with our current immigration policies.

No, the mistreatment of our immigrant neighbors these days has little to do with lack of space or jobs or crime or any of the other false justifications suggested. Rosa Sabido and her peers in sanctuary are just more collateral damage from a political war being waged from the West Wing of the White House some 2,000 miles to the east. There isn’t room for Rosa these days because someone has determined that throwing this creative, hard-working woman out of the country she has called home for the past 30 years will somehow motivate the president’s base of supporters to vote in the next election cycle.

I find it a maddening reality made more so as I travel the nation experiencing the transformation that occurs when statistics become people with names and faces, tears and tales of shattered lives… and every so often, hope.

Rosa grew up in Mexico City from the age of 4 until her early 20s. She is funny, writes poetry, loves rock music, lights a room when she smiles and is so sensitive and empathetic to living things that she cried when they cut down the diseased tree in front of the church in Mancos, Colorado, where she has entrapped herself in her effort to remain free. Sanctuary is funny that way. And she cried again when I asked her why she keeps an old limb from the dead tree next to the makeshift shrine in her room.

“Someone should remember it,” she told me.

I left it there, preferring not to hear the answer to my next obvious question.

In 1986, after visiting her stepfather Roberto — who had moved to Cortez, Colorado, a few years earlier and had recently received residency under Reagan’s amnesty — Rosa felt that Southwest Colorado might just be the perfect spot to carve out the independent life of which she had always dreamed. So, approximately a year later, after one more vacation to scope out the region, she decided to find work and put down roots in the Four Corners area.

It is a decision Rosa claims she’s never regretted. For 30 years she has called Cortez home, living in her small blue house on the south end of town next-door to her elderly and ailing mother and stepfather whom she physically cares for… or at least did until she was forced to take sanctuary in the tiny Mancos United Methodist Church on June 2, 2017, to avoid deportation.

She says she misses the sunsets over Sleeping Ute Mountain, which she could see from her home. She’s taken hundreds of photos of those sunsets over the years because, she says, “every one is different and always beautiful.”

People in Mancos know how much Rosa misses her dogs so they bring by their own pets — like the one pictured at left — and leave them with her for a few hours and sometimes even overnight. The smile says it all. Photo: Joel Dyer

While she misses her home and is deeply saddened over the absence of her five pet dogs, whom she says are getting older and need extra attention, it’s not being able to care for her parents any longer that has been arguably the most stressful aspect of living inside the church walls. She says it’s hard, knowing that leaving the church property to help them would likely result in her detention and deportation.

Listening to her describe their relationship, it’s clear they are close and that they badly need her help.

Just 48 hours before Rosa planned to enter sanctuary back in June 2017, her mother called and said her stepfather was very sick. It was right when she was trying to finalize her entry into sanctuary, a very confusing and stressful time.

“There was going to be a conference call between the pastor, my attorney and me… but that morning, my stepfather was feeling very sick. He couldn’t even walk and he was all bent. My mom was very scared and she called me, and she said that something was going on with him. And then suddenly I ended up in the emergency room, and he had some kidney stones. It was very painful for him.

“We did the conference call when I was in the hospital and we were talking what the plan was going to be for me to come, and they told me, ‘You have to be in the church by Friday afternoon,’ and this was Wednesday,” she said as she let out a sigh. “And I was like, ‘Can this be Sunday night?’ and they said, ‘You don’t really want to take more risks. You need to be there.’

“So, that next day and a half, gosh, it was crazy. I was crazy packing. It was not as warm as it is now, it was kind of cold. You don’t know what to pack, if you want to pack for the next week or for the next year, so you grab whatever you can.”

But once in sanctuary, things got even worse for her parents.

Rosa’s mom, who has a number of serious health issues already, went to visit her son in Mexico and started feeling very poorly in December 2017.

“She was visiting and she wasn’t feeling very well,” Rosa said. “So she went to get some tests… because she has high blood pressure, problems with her thyroid, liver problems. There are more, like she has an enlarged heart, she had pneumonia three years ago and damaged one of her lungs, so she has apnea, and she’s overweight and she’s short. She’s very short, so that makes it harder on her body. And now with the diabetes — even worse. So, she wanted to get her prescriptions, but she needed to go to the doctor, so she did, and they started finding things here and there, and she had some test, and they told her that she had breast cancer. … They decided to do the mastectomy.”

It’s no wonder being in sanctuary makes Rosa feel helpless at times. “Because my stepfather has to work, I told her, ‘Well, all I can do is take care of you here in this room where I’m sleeping.”

“For me,” she continued, her voice beginning to crack as her eyes teared up, “the day of her surgery was like, I’ve never been more stressed and being here, and how it was that day… I almost had a panic attack here. Because my fear was she was never going to make it. She was so sick. … I told her, ‘You might not even make it. You might be scheduling the day of your death.’ So, I’m like, ‘You’re out there, I’m here, and I really want to see you again and I miss you, but I’m not sure if that’s ever going to happen.’”

Editors note: I’m sorry to have to report that subsequent to my interview with Rosa, Her mother Blanca Valdivia passed away in July 2018. On her face book page Rosa wrote, “My beloved Mom is gone. The reason of my sacrifice is gone forever. They destroyed us, I am paying a very high price of sorrow and grief and nothing will take that away from me.”

Untitled

By Rosa Sabido

How many more moons and suns

Days and nights

Winds and rains and wasted tears

Unused minutes, eternal hours

When the future will become present

When a smile will come from a genuine happiness

When I will be able to make a plan for tomorrow

For next year

Or for the rest of my life?

When is the night that will hold beautiful dreams for me?

How many questions with no answers?

____________________________________________________

Rosa’s story has similarities to many of the others I’ve heard over the last two years. By all accounts, she’s a wonderful friend and neighbor and an incredibly hard worker, who has been nothing but an asset to her community.

She has tried to live in the United States legally, but like millions of others in her position, has found the system nearly impossible to navigate.

For her first 10 years in Cortez, Rosa went back and forth on her visa with no problems, spending nine months each year in Cortez and three months in Mexico. But then, for reasons she still can’t explain, while flying into Phoenix in 1998, she had her visa canceled and she was held in the Maricopa County jail overnight. The next morning, she was placed in handcuffs, paraded through the airport and put on a flight back to Mexico.

The only way she could get back to her home and family and pets in Cortez at that point was to pay a coyote to bring her across the border, an experience that still haunts her and which she describes as, “the last nightmare I have ever gone through.”

“Talk about hell,” she said. “And I didn’t go through what others go through. I had special treatment, because we had paid more, because I will never run a mile, I will never hide from… I will never be good enough to do it, truly. I feel for those people who cross the border, who are seven days without food, without… I have heard all kinds of stories. For me, it was terrible.

“First we tried through Juarez. They made us cross the river, which the river came up to here,” she said, holding her hand to her neck. “So it was a line of people, just follow the leader, just walk. … You don’t know where to look, front side. It was daytime, it was like noon. Outside [of town], but not far. I guess it was easier back then, but when I got to the other side and turned my face up, there was this patrol guy with this big rifle pointed at my forehead. He went and told me all of these words like, “Hey you, get out of there,” and of course I was wet all the way up to my neck.”

Eventually her family sent a cousin across the border to cross with her to keep her safe even though it doubled the price. She finally got back home to Cortez via a drainage system at the border in another city.

But her bad experience and the economics of it meant she could no longer risk returning to Mexico. She would have to rely on her efforts to navigate the confusing and expensive maze to legal status, which she had already begun years earlier.

“They said that the only way [to be here legally] is if my mom becomes a resident and she applies for you. So, we started that through my mom. My stepfather applied for my mom, and then my mom got all of this employment and authorization, and she had that for three, four, five years. It was not like by tomorrow. My stepfather had to become a citizen, which he was not really willing to do [at first], because he had to learn all of these questions and answers and talk in English, and whenever he has an interview, he was like, ‘I don’t know.’ But back in ’98 he became a citizen, and in the meantime my mom had some sort of authorization, so she was working all this time, and she became arrested in 2001. Right away, we applied and she became a citizen in 2004, but we already had the application. So, we sent a letter to USCIS [United States Citizenship and Immigration Services] to let them know that she had become a citizen so they can update the status of the application [to make me legal]. And then in 2006, the application was approved, meaning that doesn’t give me any legal status, but it gives me the opportunity that when my number comes, that year, I will be able to apply for a permanent residency. So, in 2001, that was years since we applied. And 2006, [it’s been] 12 years since it has been approved. And it’s [still] going to take another 15 to 20 years when my turn comes [because] it’s backlogged. I’m 54 years old, how old will I be? And if [my mom] dies, the application cancels automatically.”

Editor’s note: As mentioned above, Rosa’s mother passed away in July, 2018. It is unclear where Rosa’s application for legal status now stands as a result.

For years Rosa has lived quietly while she waited for “her number” to come up, but in 2017 she was suddenly told she had only a few days to leave the country.

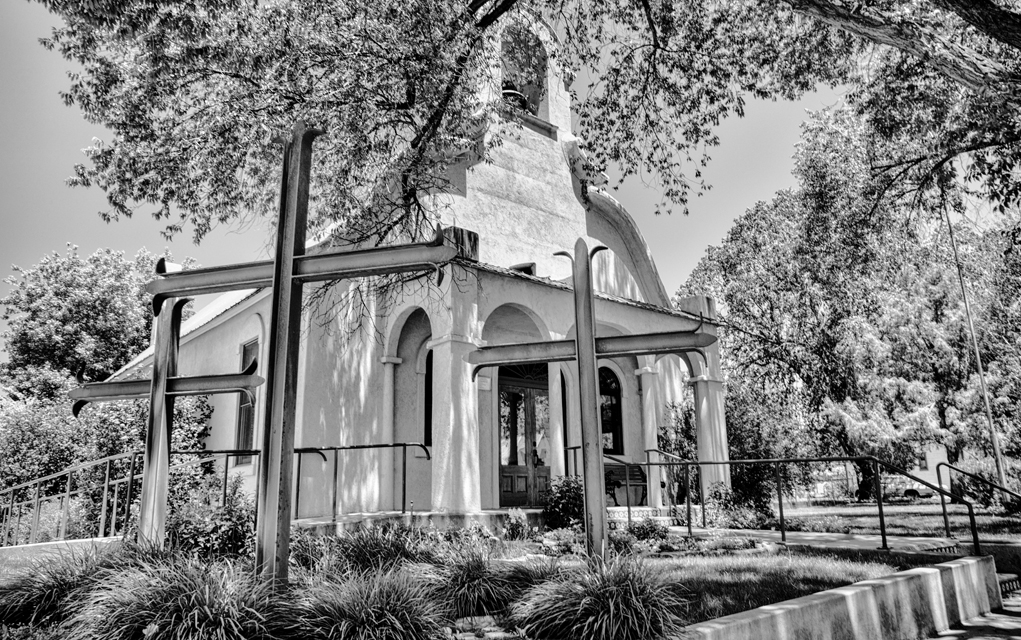

The dead branch from the tree that was cut down in front of the church is visible sticking up from the cup on the table just beyond the shrine. Photo: Joel Dyer

At the time she took sanctuary, Rosa was working at least three jobs while also trying to build her own business.

“I started from being a dishwasher to working in a hotel and then I ended up in the same place doing the laundry, the rooms and the front desk because I knew how to do all that. And they had a restaurant and I was also helping at the restaurant and I have been working at the casino and at the same time working at another restaurant and doing gardening for other people,” she said, before continuing her list. “I strip copper wire of its casing, do secretarial work for the Catholic church, do taxes on our block, do translating, you know. … I was the only person when people needed their documents to be translated into English for their documentation for immigration. They all came to me, because they hardly find anyone who could have done it in this area. And I make my food, selling, shopping and trying to build my food truck business.”

For all the different jobs she’s had, it was her “making food” efforts that made Rosa a bit of a local celebrity throughout the area from Cortez to Mancos on up to Dolores, all communities on the route where she sold her fresh tamales.

The members of the Mancos United Methodist Church had taken a vote to become a sanctuary congregation should the need ever arise long before they knew of Rosa. In fact, the only reason she knew anyone at the small adobe church that now protects her, including its Pastor Craig Paschal, was because he and a couple of other attendees were regular customers, aka enthusiastic consumers, of her tamales, the addictive qualities of which I can personally attest. Rosa can cook.

She told me that her greatest joy is to see the smile on the face of someone who has just tasted her “real Mexican food” for the first time.

“It has been my dream in this country to have my own business, a well-established business. But I had never done it because, even though back in 2000 I bought a food truck and it’s still there, my situation was never really stable. It was always like immigration, lawyers, fees, money, money, money. And you think, well, if I don’t have the status, what is going to happen? And of course, that prevents me, all of the expenses, really prevent me from starting my business. … I paid $30,000 for that truck and I bought a smaller truck, it was part of my dream. But if you see those trucks and you see my house and you see how those things look right now, it’s like how things have turned, it’s just like…They’re getting old with the dream inside. That’s what they are. And it happens to me now. I’m getting old, with the dream still inside.”

Despite the hardships of sanctuary, Rosa says she’s still optimistic because she’s a very spiritual person who believes that all the things unfolding in her life have meaning and purpose and that God is very much in control.

“I’m not planning to give up, because [being in sanctuary] is something that I’m doing not just for me but for others,” she said. “And I really want to live in a world — when the time comes, whenever I die — and feel like I did something in my life and did not live as a parasite here. I feel like life should have purpose, because when you get to this age it is really haunting, like what am I going to do? What is my mission and what is my calling?

“And suddenly I was thrown here.

“I was praying every day. And I don’t think we know what our mission is until we die, but certainly this will help me not to feel so bad. It is a big mission.”

And that mission is getting bigger.

To view other essays in this series or to learn more about the Windows, Walls and Invisible Lines project click below:

____________________________________________________

INFO BOX

WOMEN OF RESOLUTION

Sunday, Oct. 14, 2-4 p.m.

eTown Hall (1535 Spruce St., Boulder)

Motus Theater is collaborating with Boulder Weekly to bring to the stage Women of Resolution, based on interviews of the four Colorado women forced to seek sanctuary in their fight for immigration justice, and to stay with their families. Their stories will be read by members of the Colorado State Legislature — including Reps. Jonathan Singer, Leslie Herod and Joseph Salazar — followed by a poetic response from national slam poet winner Dominique Christina, and a panel of sanctuary movement and faith leaders including Jeanette Vizguerra.

Tickets to the live performance available soon at etown.org. You can also join sanctuary leaders including Ingrid Encalada Latorre to watch the free livestream at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Boulder (5001 Pennsylvania Ave., Boulder). Or contact Motus to get the livestream link and host your own watch party: [email protected]

For more information click here.