Let me explain a little bit about this ongoing project.

The dictionary defines sanctuary as “a place of refuge and protection.”

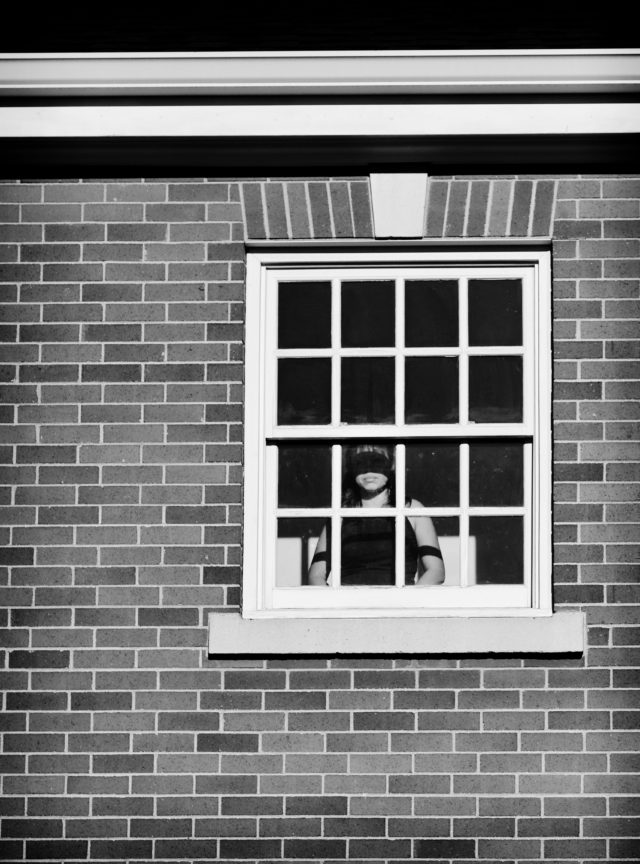

In our current political environment, it’s a word often applied to pro-immigrant efforts by religious groups, activist organizations and even entire cities. But beyond this realm of support efforts, there exists another level of sanctuary comprised of very real physical spaces — windows and walls, if you will.

These sanctuaries include churches, religious retreats, monasteries and parsonages of varying denominations. In the past couple of years, many religious locations have been transformed into literal sanctuaries by providing safe haven for immigrants who would otherwise be forcibly removed from the United States, often sent back to countries where physical abuse, violent crime, life-threatening poverty and even death await them. Not to mention separating them from loved ones, including small children.

So what is it about these religious sites that makes it possible for them to thwart the law enforcement efforts of the federal government, particularly the efforts of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)?

It’s a good question considering there are no actual laws preventing ICE from simply entering church property and apprehending whomever they want. They can do that at any time, but so far, they haven’t.

The reality is, the only thing protecting the hundreds of people who have taken refuge on church property over the last two years is what can best be described as invisible lines.

Since our nation’s founding, it has been customary for law enforcement to respect the sanctity of church property. It is a tradition based on some of our longest-held core values. And just because the lines are invisible doesn’t mean they are weak.

In one instance in New Mexico, ICE agents actually chased a man from Colombia, bumping his car with theirs in an attempt to prevent him from reaching his local Catholic church. Those agents stopped their pursuit and simply parked across the street once the man made it into the church’s parking lot.

It is a powerful line.

But for how long?

By its very nature, the current political crisis that has engulfed our nation — a crisis exemplified by President Donald Trump and his administration’s mistreatment of immigrants — is the result of our elected leaders having abandoned many of our nation’s long-held social norms. Overt racism, lying and the general ignoring of moral precedent have become the everyday behavior of the current administration, as well as its most rabid supporters and those who have chosen to look the other way because such apathy serves their political or economic interests.

Under these conditions, we should all be aware that the long-held considerations that have protected immigrants in sanctuary thus far, as well as the sanctity of our religious institutions themselves, are under grave threat. Their violation is only a tweet away.

These invisible lines of protection may be powerful, but they are also vulnerable because they are no more than a manifestation of our past cultural sensitivities, protections willed into existence by our better angels in days gone by, presumably to protect us from ourselves should darkness one day descend upon our nation.

I believe “one day” has come. And we would do well to realize that it is not just our persecuted migrant friends who are in refuge within these lines and behind these walls, it is all of us who now hope and wait for our country’s sanity and compassion to again show itself.

If these invisible barriers built of history, empathy and respect for religious freedom should fall, all of us and the country we call home will be forever changed. In many ways, these lines that form our islands of sanctuary are our nation’s last line of defense against the hatred and totalitarianism that has swept over us. For all of our sakes, we must fortify them by any and every means possible.

And that is the hope and intent behind this project.

I launched the Windows, Walls and Invisible Lines project back in May with the belief that when we come to know our neighbors in sanctuary in a way that transforms the statistics into people with faces and stories, we will become better equipped to fight the ignorance and prejudice that have become so prevalent.

As I travel the country spending a few days photographing and getting to know these amazing women, men and families, I become more convinced every day of the power of their stories.

In order to amplify the project’s impact, the dissemination of its content will be multifaceted. The interviews and photos will eventually culminate in a book, a traveling photo exhibit, a multi-month-long ongoing series in Boulder Weekly that is coordinated with Motus Theater’s UndocuAmerica Performances and Media Project.

Most of the essays will not begin running until early next year. But for a number of reasons, we’ve decided to launch the project now as it pertains to the four women who are, or were, in sanctuary in Colorado when the project launched. (Sandra Lopez and her children have recently been able to return home after more than 10 months in sanctuary in Carbondale.)

The reason for this timing is to help support the People’s Resolution, a petition effort that is the culmination of a five-month-long effort by the four women — Lopez, Araceli Velasquez, Ingrid Encalada Latore and Rosa Sabido — to identify a number of concrete steps that elected leaders in Colorado and beyond can take to create a pathway to legal status for people, including those now in sanctuary. The Resolution was created in the hope that other families won’t have to be separated and torn from their homes and lives as has happened to those now living in sanctuary or detention, or those who’ve already been deported or the millions of our neighbors now living in constant fear of such horrific scenarios.

We’ll be running an essay each week for the next four weeks culminating with an exciting event titled “Women of Resolution,” a collaboration between Motus Theater and Boulder Weekly, on Oct. 14. Click here for more details.

To view essays go to: