For a full interview with with New York Times bestselling author Christine Feehan, author of the Dark Series novels, click here.

It may be Halloween, but bloodsuckers are no longer relegated to the end of October. Like a dark cloud of mosquitoes, vampires have descended on America. They’re everywhere, from the puppet teaching our children to count to the romantic hero stealing the hearts of teenagers nationwide.

What’s strange is not that vampires are popular — for almost 200 years, they’ve had some sort of seat at the pop culture table.

“Vampires are almost never not hot,” says Mark Dawidziak, TV critic for the Cleveland Plains-Dealer whose 11th book, The Bedside, Bathtub, & Armchair Companion to Dracula, explores all things vampire.

“We always have a

period of continual interest in the vampire character. So in the 1950s,

you can have Christopher Lee becoming a star in Hammer Horror films. In

the 1960s you can have Dark Shadows as a pop culture phenomenon… leading into this decade, where we now have the emergence of the ‘chick-lit vampires’ on True Blood and Vampire Diaries and Twilight.”

What’s strange is how vastly different

vampires of the 19th century are from the

vampires of 2009. What separates vampires

from other horror creatures is how

they’ve changed over time, showing

remarkable adaptability to whatever

America requires of them. While zombies

have pretty much one role in popular culture,

vampires’ role has mutated dramatically

and adapted to fit the times; media

marketing machines have tapped into their

mystique and created new incarnations to

keep public interest high and money rolling

into the bank.

“[Vampires] are a constant in the culture

because they are a perfect metaphor:

the vampire casts no reflection in the mirror.

So therefore, we look into the mirror

and we see what stares back at us, and we

constantly reinvent the vampire as a character,

generation to generation, era to era,

to reflect our fears, reflect our insecurities,

reflect our wishes and wants,” Dawidziak

says.

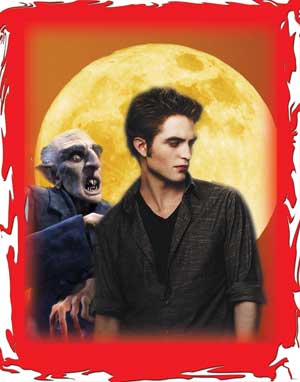

So then, from the grotesque Nosferatu

to sparkly Edward Cullen, each generation

gets the Dracula it deserves. My generation,

it seems, deserves a sanitized, PG

Dracula. The character Bram Stoker created

in 1897 is a being without a conscious,

a monster who is human only in physical

appearance. He is, in the words of retired

academic Elizabeth Miller, author of seven

books on vampires, “evil incarnate.” The

current version of the vampire mythos, as

evidenced by the enormous popularity of

the movie Twilight and the HBO series

True Blood, presents vampires as ideal

romantic heroes — bad-boy outsiders,

tough enough to protect the girl from evil,

yet sensitive enough to introduce to the

parents. The vampire, once one-dimensionally

evil, has evolved into a complicated,

brooding pretty boy.

In this regard, Twilight and True Blood,

the former based on the incredibly popular

teen romance novels by Stephenie Meyer,

the latter based on the almost-as-popular

Sookie Stackhouse novels by Charlaine

Harris, have some things in common. Both

male vampire heroes, who are much older

than the heroines, become awkward and

stiff after meeting the loves of their lives —

young, naive (and in Twilight, underage)

virgin girls. During the courtship, both

vampires, children of the 19th century, after

all, maintain a sort of rigid Cotillion formality.

Even the romantic hook of both

plotlines is exactly the same, with roles

reversed: In Twilight, leading high school

psychic vampire Edward Cullen finds himself

madly attracted to new-girl-in-school

Bella Swan because he cannot read her

mind. True Blood’s Sookie Stackhouse can’t

keep her telepathic thoughts off of vampire

Bill Compton because his mind, unlike the

everyday humans surrounding her, is

unreadable.

In the most dramatic departure from

traditional vampire lore, Bill and Edward

fight their vampirism and cling to their

humanity — a case of “vampire guilt,” if

you will. Bill subsists on a Japanese synthetic

blood substitute, and Edward only

drinks animal blood, coyly calling himself

a vegetarian.

{::PAGEBREAK::}

The idea of the reluctant vampire originated

in the 1960s and continues strong

today, Dawidziak says. The TV series Dark

Shadows started it.

“They made [Barnabas Collins] the

first vampire character who questions his

own nature. This had never been done

before… He was known as the vampire as

Hamlet… This sets everything up on a tee

for Anne Rice in the ‘70s and her endlessly

introspective vampires. It also sets it up for

the heroic vampires to follow,” he says.

The approachable vampires on the

market today were bred by romance novels

before making their way to television and

cinema, and many say author Christine

Feehan, whose Dark Series novels exploded

onto the romance scene in 1999, selling

millions of copies and topping bestseller

lists, is responsible. The series stars the

Carpathians, a vampire-like race, and now

includes 20 books. Feehan says vampires

make for great romance heroes because

their vampirism is an excuse for their

alpha-male characteristics, which in a regular

man would seem unbelievable.

“You have a lot more scope, where

[vampire romance heroes] can be oldworld

and courtly, and they can be arrogant

and powerful and deadly but still be

[acceptable], which a modern-day man in

a contemporary story cannot — you have

to keep them very politically correct,”

Feehan says. “But a vampire doesn’t have

to be. He gets to bend all the rules, and

you can make him a good guy or a bad

guy, and there’s always that edge of danger

you’re writing about.”

So, perhaps taking away the male’s

humanity and replacing it with paranormal

myth allows an author to remove the

shackles of political correctness from the

male hero, permitting him fulfill a much

racier female fantasy.

“Well, [male vampire heroes still] have

to be human,” Feehan says. “You know, it’s

a very interesting thing. Women, when

they write to me about this, I remember

one letter in particular struck me, and she

was saying how her husband was so wonderful

and how they had kids, and he

worked two shifts, and she was like, ‘But I

dream about one of these Carpathians.’

And I wrote back to her, and I said, ‘That

man is slaying dragons for you… He’s

doing the things a modern man has to do.’”

Vampires embedded themselves into

the popular psyche, fittingly, during the

Romantic Era, at the hands of one of the

period’s most famous figures, the poet and

aristocrat Lord Byron.

On a stormy summer night, Byron and

his personal physician, John Polidori, found

themselves holed up in a lakeside villa with

the poet Percy Shelley, Mary Godwin, and

Godwin’s stepsister Claire Clairmont.

Caged indoors by the bad weather, the

group resorted to reading ghost stories to

one another. Afterward, Byron suggested

the group write their own tales and share

them with each other.

Two of the most enduring monsters in

horror fiction came from that night. While

Byron produced little of note, Godwin,

who eventually would marry Shelley,

began writing what would eventually

become Frankenstein, and Polidori wrote

the beginnings of what in 1819 he would

turn into The Vampyre — the piece that

propelled vampires into the era’s psyche as

plays and operas starring vampires became

fashionable.

“Polidori based his vampire on Lord

Byron, and that made [the character]

extremely popular,” Miller said. “They’d had

a falling out before because Byron had fired

him, and it’s generally believed that he did

this to Byron as a form of revenge.”

Lord Byron and Dracula shared sex

appeal, if nothing else. The common

image of a vampire is a predatory Don

Juan, and an undercurrent of sexuality

penetrates deeply through most forms of

vampire fiction.

“The vampire symbolizes the masculine,”

says sexologist Jenni Skyler, noting

that with male vampires, “denied masculinity

is allowed to come forth.”

Many women have submissive fantasies,

she said, but cultural attitudes that

frown upon nontraditional sexual activities

can shame women into not expressing

them. Vampire romances, she said, provide

women with a safe outlet for these fantasies.

“At the end of the day, it’s that world

where in a country that’s puritanically

prudish, we often need permission just to

fantasize,” Skyler said.

The vampire is a timeless, immortal

mainstay in horror literature, possibly

because, as Dawidziak points out, there are

simply very few original ideas in the horror

genre (hence the beating of the dead

horse that produces Scream IV, Saw VI).

So when a good one comes around, the

media bites down hard and feeds until satisfied.

Vampires have offered their necks to

entertainment for nearly 200 years, and

the thirsty public has happily drank.

Vampires have spiked in popularity before,

Dawidziak says, and in the future, after

this wave of vampire popularity has receded,

he adds, maybe somebody will scratch

their head and ask, “Remember when

vampires were romantic?” Only time will

tell if the answer will be yes or no.