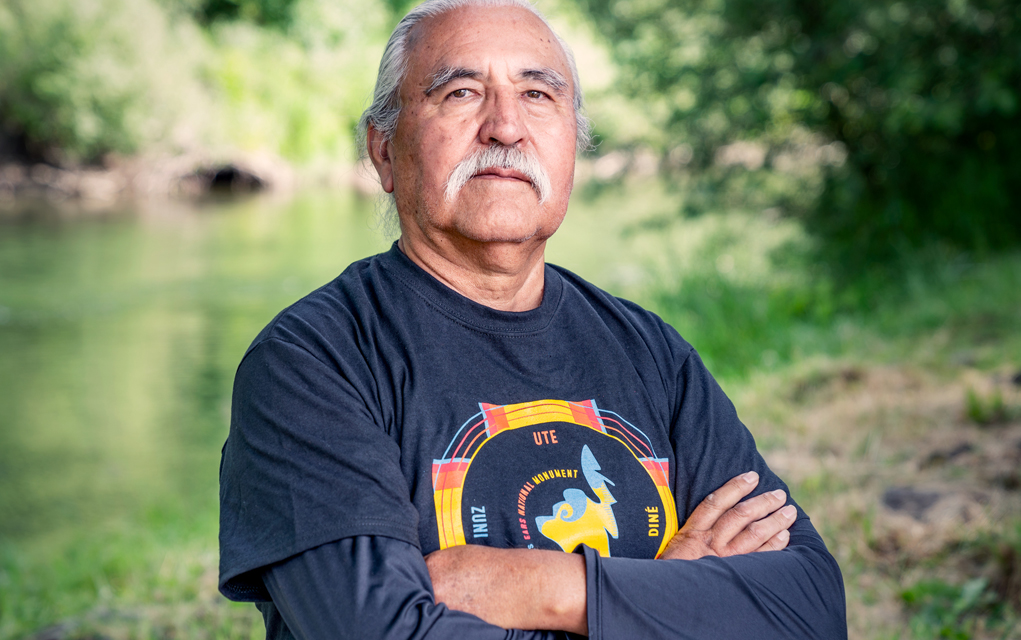

This story, you don’t tell it in the summertime. According to Navajo tradition, some tales are meant to be shared on the warm nights that bleed gently into Utah’s blushed sandstone; other stories are saved for when the purple-gray shadows creep up early on winter afternoons. This story, Davis Filfred explained to me one day in May, the one about Bears Ears — this is a winter story.

Later that night, on stage, facing a ballroom packed with white tablecloths and blue-hued ties on the third floor of Denver’s Hyatt Regency, Filfred inhaled deeply, pressing a glass prism to his nose. The delegate from the Navajo Nation 23rd Council — representing the Aneth, Mexican Water, Red Mesa, Teec Nos Pos and Tólikan chapters — leaned into the podium microphone. “Whenever you get something, we inhale its spirit,” he said. That way it can never be taken away. “That’s how we embrace.” Slowly, he drew another inhale.

Only minutes earlier, Colorado Senator Michael Bennet had hugged Filfred as he’d walked across the stage, prism in hand, through the applause of nearly 1,000 people in the room. Filfred — on behalf of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition (BEITC), a multi-tribe advocacy organization lobbying for the protection of land profoundly sacred to many indigenous cultures — was being honored as one of Conservation Colorado’s 2018 “Rebels with a Cause.” Willie Grayeyes, a representative from the grassroots Navajo organization Utah Diné Bikéyah, which had spearheaded BEITC, was the award’s other recipient. It was at this event that I first met and talked with Filfred and Grayeyes. “Because of their hard work,” Sen. Bennet said, introducing the two Navajo men, “President Obama designated Bears Ears as a national monument in December of 2016.

“This historic collaboration between indigenous groups and the federal government began to turn the page on centuries of broken promises,” Sen. Bennet continued, “until Donald Trump broke America’s promise once again, deciding illegally, in my opinion, to slash Bears Ears by 85 percent. If this decision stands, it opens the door to attack national monuments not just in Utah, but here in Colorado and all across America. We cannot let that happen. And that’s why your selection,” he gestured to the crowd, “of these honorees tonight is so important.”

As Filfred stepped to the podium, the crowd roared, then quickly fell to a hush. It’d been nearly six months since Trump’s highly publicized (and, in the circles that mingled this night at the Hyatt, highly criticized) order to reduce the boundaries of both Bears Ears and Grand-Staircase Escalante national monuments in southeast Utah, setting in motion the largest rollback of federal land protection in U.S. history.

Designating Bears Ears as a national monument was one of former-President Obama’s last acts in office. Only 23 days before leaving the White House, he’d invoked the Antiquities Act, a political pathway carved in the U.S.’s early, exploratory 1900s that gives presidents the power to bestow extra protections on vulnerable landscapes containing artifacts of historic, scientific or cultural importance.

Obama’s actions were in response to a proactive group of five Native American tribes — Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute and Ute Mountain Ute, now known as the BEITC — who had, for the first time in U.S. history, spent years setting aside deep historic rifts in order to collaborate on the collection of both scientific data and oral histories that could prove to the federal government the everlasting significance of the region in southeast Utah. They wanted to convey Bears Ears’ need for protection, not only contextualized in each culture’s history, which extends back to time immemorial, but in the land’s modern-day significance, too. By the time Obama designated Bears Ears, 26 Native American tribes had voiced their support for the monument, as monuments are more sheltered from looting, resource extraction, human development and recreational activities than other federally owned lands.

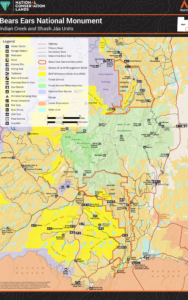

But almost a year ago, on Dec. 4, 2017, Trump reversed years of the groundbreaking collaboration between multiple indigenous tribes and the federal government with the stroke of a pen, effectively re-opening the area to such threats. Bears Ears National Monument was split and shrunk into two sections: Indian Creek and Shash Jáa, roughly 201,397 acres in total (15 percent of its original size), divided and separated by a 50-mile-long, 70-mile-wide channel of now-vulnerable land. Grand-Staircase Escalante and its rugged, pristine terrain that was the last area to be mapped in the contiguous U.S. was carved, too, nearly in half, from 1.8 million acres to just over 1 million.

That same December day, however, two other legal steps were taken. In one building, Utah Republican Representative John Curtis proposed to Congress a bill that would set in motion new plans for the management of the Bears Ears area, one that would balance local energy development and constituents’ ranching needs. In another building, the Navajo Nation, Native American Rights Fund (NARF, representing the Hopi Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni and Ute Mountain Ute Tribe), and the Ute Indian Tribe jointly filed a lawsuit to defend the original boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument — marking the first time these Native American tribes have banded together to challenge the federal government, and the first time a presidential act like this is being be challenged in court.

“I’d say that’s perhaps the most fascinating facet of this issue, because a lot of complex and often painful history exists between some of these tribes,” says Rebecca Robinson, who spent the last three years traveling through and collecting stories from people living and working in the region to write the book Voices from Bears Ears. “[It’s] amazing given recent and past history that they were able to come together and say, ‘Look, we still have some conflicts and we have some painful history, but we have this in common and the only way we’re going to be able to protect the sacred landscape is [if] we band together.’”

Historically, a national monument designation has acted like the first domino in a line of political actions that leads, eventually, to an upgrade to a full-blown national park and even deeper layers of land-use protections. The majority of national parks in southern Utah — Arches, Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon and Zion — all started as national monuments, according to Mark Squillace, a law professor at the University of Colorado Law School.

But, it seems when the executive baton was passed from Obama to Trump in 2017, traditional public land policy took a dramatic turn off-course. “The Antiquities Act,” Squillace says, “gives the president the authority to reserve national monuments. It doesn’t say anything about his authority to shrink.”

When Trump re-issued his own Dec. 4, 2017 proclamation under the Antiquities Act, it wasn’t a new national park that was kickstarted, but the latest high-profile face-off between the federal government and five sovereign Native American tribes. No one knows where these dominos will lead, or fall.

Time immemorial

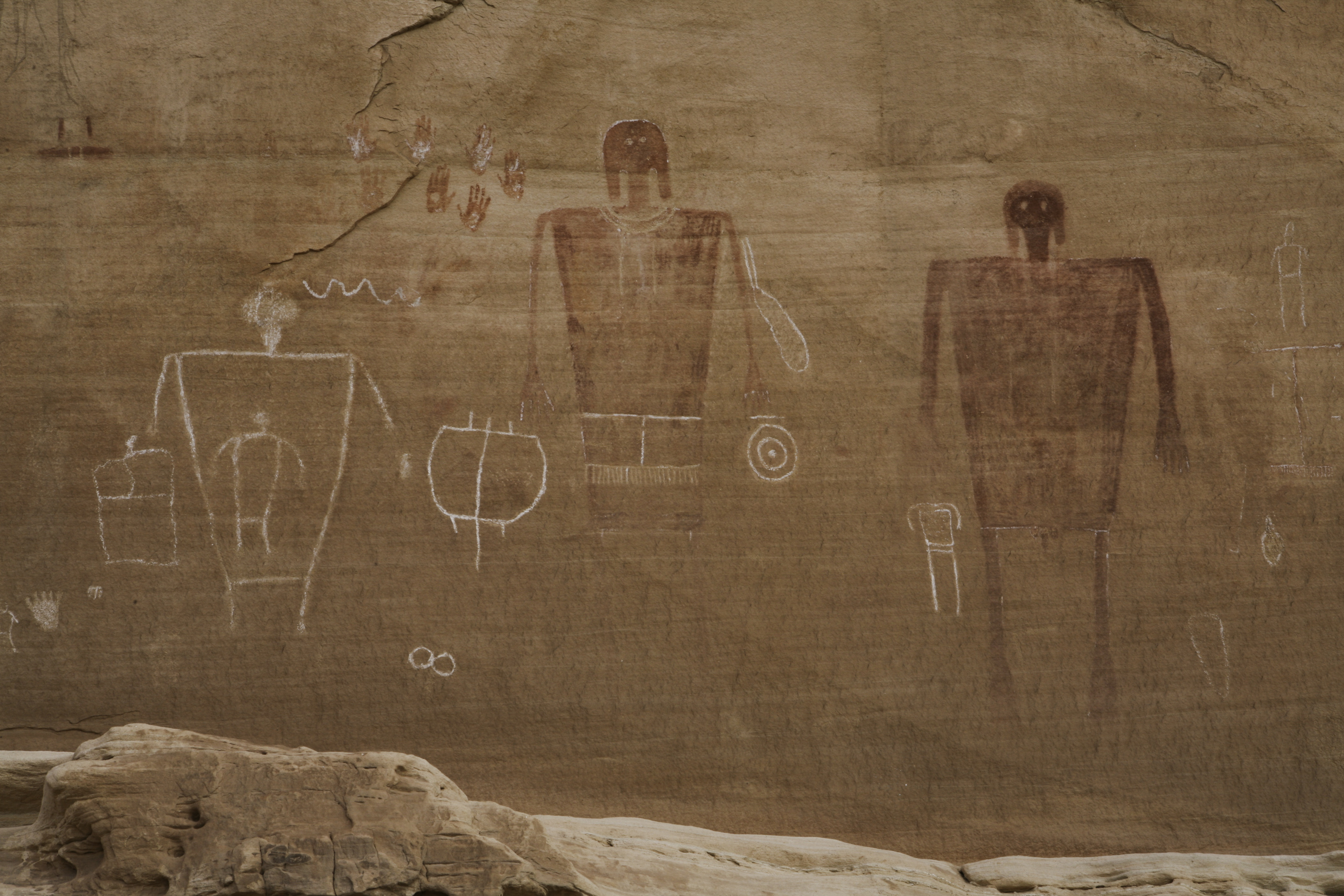

Forty miles south of Moab and 12 miles east of U.S. 191, past the wind-worn sandstone arches and dilapidated wooden corrals, a small asphalt parking lot is tucked between steep canyon walls. Signs point to what’s now known as Newspaper Rock, a 200-square-foot slab of Wingate sandstone covered in petroglyphs, or stone etchings, dating back as far as 2,000 years. According to the BLM, the preserved images are from Archaic, Basketmaker, Fremont, Pueblo, Anasazi and Navajo peoples who passed through, possibly stopping at the natural spring that seeps from the sandy rocks nearby.

Navajo people refer to the slab as Tse’ Hane, “rock that tells a story,” and it serves as a sort-of entryway to Indian Creek, the northernmost pod of the new, divided Bears Ears National Monument. A six-toed foot and a bighorn sheep are etched next to a wheel; a hunter on a horse treads next to a slithering snake. From Newspaper Rock, continue eight more miles north, turn left on a graveled road, and head to a cliff band deep in the valley that modern-day rock climbers refer to as “Sparks Wall.” Another reminder of the area’s history stands in an 800-year-old, multi-story cliff dwelling that’s camouflaged hundreds of feet up from the basin floor; wooden ceiling beams remain intact; pottery shards have been pooled; red pictographs line a wall. In 2016, Obama noted over 100,000 unique sites of historic, cultural and scientific importance, including prehistoric fossils and early human migratory clues, exist within the monument’s original boundaries.

“You have a huge experience of human history out here,” says Lyle Balenquah, a Hopi archeologist and river guide who has watched dozens of seasons come and go in the Bears Ears region. For the past 20 years, Balenquah has been helping the National Park Service (NPS) interpret cultural and paleontological sites and promote indigenous perspectives of U.S. land. Reducing protection of the area will compromise new and old artifacts and fossils, he worries, as only about 5 percent of the region has been properly surveyed thus far. “We’re talking 12,000 years [of history] or more here, and it’s all important.”

The name Bears Ears comes from twin buttes that rise from the sage-speckled floor of Cedar Mesa, located in the new monument’s southernmost pod, Shash Jáa. From as far as 60 miles away, south or east, one can see the two distinctive buttes rise, looking like a bear about to poke its head up from the horizon. In recent reporting, the area around the Bears Ears Buttes have been described as a Native American version of Eden — their birthplace of humanity. Today the Ute people still graze livestock, hunt and gather in the region. Navajo people still perform prayers and sacred ceremonies. Hopi and Zuni tribes look to this land as evidence of their migration stories and medicinal traditions. As BEITC states on its website, “Protection of the Bears Ears region from irresponsible off-roading and the depletion of irreplaceable cultural resources is important to maintain the cultural connections of many Native peoples.”

Hunter-gatherers first visited the Bears Ears area about 10,000 years ago, but only 2,000 years ago did Native American tribes start to settle more permanently. Indian Creek was the southern limit of the Fremont culture and the northern limit of the Anasazi and Ancestral Puebloans. In the space stretching between awe-inspiring buttes and free-standing sandstone towers, clans grew corn, squash and beans. After a peak around the year 1200, the early residents steadily declined, leaving behind an abundance of rock art, dwellings, pottery, mokie steps and other evidence of their inhabitance. After that, Navajo groups started to appear, but it seems only to have been on a seasonal or temporary basis. Since then, their traditions have held this landscape as sacred, and it was in these deep maze-like canyons and remote mesas that many Navajos sought shelter from both Kit Caron’s brutal occupation of Navajo lands and the U.S. Army’s forced relocation to reservations on the New Mexico and Oklahoma borders. In 1818, Navajo war chief Manuelito was born near the Bears Ears buttes, and he later rallied and focused Navajo resistance to the “Long Walk,” another forced relocation effort. It was Manuelito who eventually helped secure the 1868 treaty — the first official acknowledgment of Native American tribal sovereignty — that allowed the Navajo to return to some of their homelands, now the current reservation.

It wasn’t until 1859 that Anglo settlers started to seriously explore the region, mostly looking for ways to monetize the rugged land — promptly upsetting what had been, up until then, a relatively natural order of being. At that point, most of the land east of the Mississippi had been settled and developed, but Utah remained relatively unaltered by Anglos, as it remained a part of Mexico until 1848. Due to conflicts with the early Mormon settlers over issues like polygamy and the separation between church and state, U.S. law didn’t take effect in the area until 1869, making Utah the last place in the continental U.S. where the “public” land out of which they’d forced the Native Americans was opened to private ownership. San Juan County, stretching about the size of New Jersey from Lake Powell to the Four Corners borders, was finally organized in 1880.

It wasn’t until 1859 that Anglo settlers started to seriously explore the region, mostly looking for ways to monetize the rugged land — promptly upsetting what had been, up until then, a relatively natural order of being. At that point, most of the land east of the Mississippi had been settled and developed, but Utah remained relatively unaltered by Anglos, as it remained a part of Mexico until 1848. Due to conflicts with the early Mormon settlers over issues like polygamy and the separation between church and state, U.S. law didn’t take effect in the area until 1869, making Utah the last place in the continental U.S. where the “public” land out of which they’d forced the Native Americans was opened to private ownership. San Juan County, stretching about the size of New Jersey from Lake Powell to the Four Corners borders, was finally organized in 1880.

As Utah was granted statehood in 1896, the federal government still owned a vast majority of its land. So, people in Washington D.C. organized what they called “trust lands” to support state institutions, such as public schools, by leasing and selling off resources and extraction rights on the land. By the early 1900s, San Juan County was largely an agricultural patchwork of fruit orchards and vegetable farms, most of the land still being leased from the federal government. In 1905, the Denver and Rio Grande railroad reached San Juan County, and it became a major shipping point for sheep and cattle.

It wasn’t until 1950 that things really started to change. Oil and gas extraction had finally come the county and brought in thousands of people, increasing the population 763 percent in just 10 years, according to San Juan County records. The New York Times reports Utah has generated more than $1.7 billion in revenue to support its public schools from the trust lands, “mostly by selling off mineral rights and allowing private companies to extract oil or gas.”

Today, less than 6 percent of San Juan County’s 5,514 square miles is privately owned, and as of 2017, San Juan is the poorest county in Utah. So, when conservative Utah state representatives and some locals heard that 110,000 acres of these trust lands would be included in Obama’s original Bears Ears National Monument, eliminating potential resource sales and shrinking their livelihood, it was time for them to head to the federal government with a plea, too.

Meanwhile, across the country

On the southern side of Independence Avenue, across the street from the U.S. Capitol building in Washington D.C., tribal leaders and select San Juan County officials filed into the main committee hearing room in the Longworth House Office Building on the morning of Jan. 30, 2018 — seven weeks after Trump’s reduction order. They were convening for the second time to discuss the bill Utah Republican Representative John Curtis had proposed to the House Committee on Natural Resources on the same day as Trump’s proclamation. The bill would officially terminate Obama’s proclamation, arguing it was massive federal overreach, and enact a new pathway for the management plans of the two reduced monument-islands, appealing to local ranching and energy needs.

It was the Committee’s second hearing on the bill — a rare occurrence — but objections had been raised during the first hearing, held on Jan. 9, when only one five-minute window of testimony was allocated to the five tribes, whereas three five-minute windows were reserved for Utah Governor Gary Herbert, Koch brother-supported lobbyist Matthew Anderson, and Suzette Morris, a Ute Mountain Ute woman who opposes the Bears Ears National Monument campaign.

At both January hearings, tribal leaders made it clear they oppose Rep. Curtis’ bill. Several lamented they weren’t consulted about the new management plans, and that the name “Shash Jáa” — Navajo for “Bears Ears” — was not only deceptive, but also intrinsically insulting. Years earlier, BEITC had collectively decided upon use of the English translation of “Bears Ears” in order to promote unity among the tribes.

Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye testified at the second hearing. “In addition to providing a misleading bill name to suggest that the Navajo Nation supports the bill, [it] also misleadingly states that its purpose is to ‘create the first tribally managed national monument,’” he said, according to the Sierra Club. “In fact, the miniature monuments created by the bill would be managed by appointees of Trump made in consultation with the Utah congressional delegation and would be composed of only a fraction of tribal members. Incredibly, no tribe would have any input on the tribal members appointed to the management councils, and those individuals would not be required to be elected or appointed representatives of the five tribes’ governments. This bill’s ‘tribal management’ is tribal in name only.”

The transition from intimate involvement in the monument’s first rendition to a complete absence in consulting on the second was unsettling, and tribal leaders accused San Juan County and the Department of the Interior (DOI) of cherry picking Native voices that supported their own views and objectives — a practice not unfamiliar in U.S.-tribal politics.

The transition from intimate involvement in the monument’s first rendition to a complete absence in consulting on the second was unsettling, and tribal leaders accused San Juan County and the Department of the Interior (DOI) of cherry picking Native voices that supported their own views and objectives — a practice not unfamiliar in U.S.-tribal politics.

“How would you like it if Russia or France went around the United States government to negotiate with private citizens?” Tony Small, vice chairman of the Ute Business Committee, asked the committee at the Jan. 30 hearing. “This is an attack on our sovereignty and violates the government-to-government relationship with the Indian tribes.”

Tribes are fiercely proud of their sovereignty, which was negotiated over many painful decades after more than a century of persecution. Pat Gonzales-Rogers, the executive director of BEITC, explains, “The basis of the government-to-government relationship is the elected leadership of tribal government speaks to the elected leadership of the federal government.”

Thus, when U.S. policy relates to tribes, what is supposed to happen is direct negotiation between the U.S. government and Native tribal government, which should respect both nations’ self-determination and rights. The states tribes may inhabit should theoretically stay on the sidelines. What is happening in Bears Ears “does not seem to be within any kind of fairness, nor does it meet any parameters of what the legal instruction is specific to this,” says Gonzales-Rogers.

In February, Rep. Curtis admitted to constituents in San Juan County that his bill was likely dead, but he was planning to alter it and eventually present it again. A few weeks later, in March, internal agency documents procured and published by the New York Times revealed Utah’s interests in manipulating Bears Ears boundaries had been stirring as early as March 2017, a month before Trump had publicly announced Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke would commence a sweeping review of national monuments.

Emails revealed Republican Senator Orrin Hatch’s office had sent an email to a senior official in the DOI in March 2017 that contained a PDF map depicting “a boundary change for the southeast portion of the Bears Ears monument. … Adopting this map would ‘resolve all known mineral conflicts,’” the email states, referring to oil and gas sites on the land. The map was incorporated almost exactly into Trump’s order.

Gonzales-Rogers says, “To have such a differential role to the state of Utah … really kind of bypasses through political conscription the duty [the federal government] owes back to the tribes. … I would think they would have a better dexterity and granular kind of understanding of Indian law and policy.”

Gonzales-Rogers says, “To have such a differential role to the state of Utah … really kind of bypasses through political conscription the duty [the federal government] owes back to the tribes. … I would think they would have a better dexterity and granular kind of understanding of Indian law and policy.”

Many wonder if Trump’s order was much more than a favor to Sen. Hatch for his support during the 2016 presidential campaign. “They targeted those two monuments (Bears Ears and Grand-Staircase Escalante) for a very specific reason, that being Orrin Hatch and the Utah delegation really had Trump’s ear,” Robinson, author of Voices from Bears Ears, says. “I don’t think [Trump] had any particular stake in this issue.”

“Bears Ears was an easy target for him,” CU Law Professor Squillace says. “Not a lot of thought that went into this.”

Thus, when Utah representatives ignored the leagues of tribal claims and lobbied Trump to null the relationship BEITC had built with the federal government, and instead pursued their own plans for manipulating and managing the Bears Ears region without Native American consultation or consent, it was clear the state was reinforcing Trump’s new line of public land policy. The path leads in a direction against which the tribes have been actively lobbying for years: toward more resource extraction and unregulated use of their sacred homeland.

Challenging Trump

“You’re talking about the heart of the Navajo people in terms of the spiritual, psychological, physiological, social, [and] the environment,” Grayeyes says as he pours me a glass of water, settling in to tell a story. He grew up on Navajo Mountain herding sheep with his grandmother, and in the early 2010s, when he was appointed as chair of the newly formed Navajo conservation organization, Utah Diné Bikéyah, he helped orchestrate the first-ever Native-directed surveys to capture what relationships between Navajo elders and medicine people still existed with the Bears Ears land. Increased signs of looting, desecration and other environmental threats in the region had put Navajo leadership on high alert in recent years, and the singular ranger that the BLM provided was not enough to protect the tens of thousands of rich archaeological and paleontological sites in the region. “We gathered all the raw data and analyzed it, and it came out that the interest was still there, still in the hearts and minds of the Navajo people,” he says. “We are still trying to tell [the state and federal government], yes, this Bears Ears region was and still is our church.”

He tells me about the effect seeing artifacts like ceremonial drums in exhibits or on displays can have on a Native person. “Just like mass shootings in Texas, and elsewhere, you think: Why? Why? That type of question is never answered.

“The concern that I have,” continues Grayeyes, also referring to the history of Native American persecution, “is that these conditions, these traumas are still there — spiritual trauma, psychological trauma, social trauma, environmental trauma. … Grave robbery, desecration of you name it, those were uncalled for, and to set those things straight is to have those things properly brought back, in terms of healing ceremonies. Then you could make it right. That way people of our generation would be in peace, you would say.”

Utah Diné Bikéyah brought its findings, objectives and goals to the commissioners of San Juan County, the district where Bears Ears lies, in 2013, but it didn’t seem to make a difference. “We had a battle going round and round for a couple years,” Grayeyes says. So, the organization enlisted the help of the Hopi, Zuni, Ute and Ute Mountain Ute tribes to approach Obama directly — exercising their government-to-government relationships with the federal government as sovereign tribal nations. Obama’s original monument was the first-ever jointly managed national monument involving direct input from Native Americans.

“This is our land,” Filfred tells me. “I know there’s a lot of energy people that just want to get in there. And we’re saying no. We want this place protected as it is. So the future generation can come and see here, and that’s where I come in, and I was given the responsibility by my council to protect this. I will stand firmly and do whatever necessary.”

The lawsuits filed by the tribes in the U.S. District Court for Washington D.C. against Trump’s actions on Dec. 4, 2017, were consolidated into two cases: one addressing Bears Ears and one addressing Grand-Staircase Escalante. By the first week of February 2018, however, NARF reported the revoked lands “were opened to ‘entry, location, selection, sale’ and ‘disposition under all laws relating to mineral and geothermal leasing’ and ‘location, entry and patent under mining laws.’”

And mining claims in the area have indeed been filed, Squillace says, though he can’t point to any particular activity that’s going on that compromises the protection of the lands in the original monument. “One of the biggest concerns is that, under the general mining law, people might go in with off-road vehicles and try to service their mining claims.”

Coalitions of nationwide environmentalists and outdoor recreation enthusiasts have both heavily supported tribal efforts and spearheaded their own resistance to Trump’s actions, too, with major companies like Patagonia advocating for public involvement across the country, even suing Trump themselves.

After the tribes filed their lawsuits against Trump, the administration asked to transfer them to a Utah court, but, arguing that the cases affect more than one state’s residents and have nationwide importance, the tribes filed a motion to keep them in Washington D.C. It wasn’t until Sept. 24, 2018 that presiding Federal Judge Tanya Chutkan ruled both cases would stay in D.C., “and that the Department of the Interior must alert the tribes at least 48 hours before they allow any ground disturbing activities on the disputed lands,” NARF reports, stating this was a win for the Native groups.

On Nov. 16, Utah Diné Bikéyah reported over 200,000 public comments were submitted to the BLM during the public comment period on potential new management plans, asking the agency to halt the Bears Ears planning process. Three days later, a coalition of 11 state attorneys general filed an amicus brief supporting the tribes and environmental groups in their lawsuits, stating Trump’s actions not only inaccurately interpret the Antiquities Act, but also harm states by disrupting partnerships with the federal government to preserve and protect precious archeological, historic and scientific resources.

The Justice Department, however, has stated the law and history are on Trump’s side. “The Antiquities Act does not give presidents unlimited power to put land in national monuments. The monuments must be confined to the smallest area compatible with protecting cultural resources.”

Trump isn’t the first president to reduce a national monument’s boundaries, but it’s been half a century since the last shrinkage. During World War I, President Wilson cut the state of Washington’s Mount Olympus National Monument in half, allegedly to source spruce tree timber to build wartime ships, but its boundaries were later reinstated and the monument was converted into Olympic National Park. While the Antiquities Act is clear in how to proclaim national monuments, Squillace explains it’s silent on how to reduce or revoke them, leaving the future litigation of Trump’s actions in uncharted waters.

Trump is, however, the first president to be challenged for this type of action. “In this case we’re arguing that the delegation [of power] is limited,” says Squillace. “It’s a delegation of authority just to reserve lands, not to take them away. If Congress doesn’t like the decisions that the president makes, Congress can of course reverse those decisions or modify the decisions that are made, but Congress has never basically taken away any significant monument that was declared by a president.

“It’s hard to know exactly what’s going to happen in any litigation,” he continues, “really anything can happen. But I think [there’s] a pretty strong case to make these decisions by Trump illegal.”

‘Now… we wait’

Amid history’s bleak track record for Native American rights — as the lawsuits fall on the heels of confrontations over the Dakota Access Pipeline, Keystone XL and protections in the Bering Sea — there is hope among Native Americans and environmental groups that policy involving their ancestral lands may again change course.

“I view this as an opportunity for young Native people to be involved, not just for the sake of it, but to actually create an insertion point of succession and planning of what Native leadership is,” BEITC’s Gonsalez-Rogers says. “Whatever we do … we hold these positions for someone else. They don’t mean anything to us unless we are passing it down. That is, for me, what a lot of the work of Bears Ears is doing: preserving this place and mindset for a generation and a generation after that.”

Voices from Bears Ears author Robinson says she’s seen some optimism on the national front, too. “I think they may have set a really good precedent and created a template for other tribes to protect their ancestral lands,” she says. “Out of all of this mess, what’s most promising is that we see a real ripple effect [that can] change the conservation movement and elevate the voices of historically underrepresented groups who really are the First Peoples of the planet.”

Now that the lawsuit will stay in D.C., all that’s left to do is wait and continue advocacy work on the ground in Utah, says Gonsalez-Rogers. The Trump administration is moving forward with creating new management plans without the cooperation of any tribal leaders, as they’ve all refused to work with the federal government until there’s a court ruling. Cooperating agencies that have elected to be involved in the planning process include San Juan County, Monticello and Blanding cities, the State of Utah, School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration, the State of Utah and federal agencies, including the Forest Service, NPS and BLM.

Now that the lawsuit will stay in D.C., all that’s left to do is wait and continue advocacy work on the ground in Utah, says Gonsalez-Rogers. The Trump administration is moving forward with creating new management plans without the cooperation of any tribal leaders, as they’ve all refused to work with the federal government until there’s a court ruling. Cooperating agencies that have elected to be involved in the planning process include San Juan County, Monticello and Blanding cities, the State of Utah, School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration, the State of Utah and federal agencies, including the Forest Service, NPS and BLM.

In the meantime, unity among the tribes and grassroots organizations continues to grow. In a historic November election, Grayeyes was elected as the second Navajo on the three-person San Juan County Commission. “For the first time, Navajos, who hold a slight majority in the county, will see that reflected in their governing bodies,” the Navajo Times reports. “The San Juan County Board of Education also emerged from the election with a Native majority.”

As Grayeyes prepares for his years ahead in public office, he’s looking forward to uplifting Native voices in all state matters, not just in the context of Bears Ears.

“So different are the Native American perspectives on resources, natural resources. How they understand them, how they interpret them, is totally different from how dominant society, the federal government, state government, county government interprets them. So that is the reason why we continue to stay involved and hopefully the lawsuits that we placed to reinstill or reinstate the initial proclamation would be realized sometime soon down the road,” Grayeyes says.

“So is it rightful for a sitting president to unilaterally quash a standing, established proclamation or policy? That is the question to this day.”