Brooks Fickett called at 9:23 p.m. on Friday — about the time Hurricane Harvey was making landfall on the Texas coast.

“Here are my hurricane predictions,” he said. “1.5 to 2.8 million people are going to be without homes. Eighty-five percent of homes will be uninhabitable.”

That was a pretty radical prediction, and I told him so.

“It’s based on the physics of the storm and the number of people and structures in its path,” he said. “The storm is 500 miles across. It has the potential to come in as a Category 4 [hurricane], hang around for days, and then go back out into the gulf, strengthen and pick up more water, and then come back in…”

By late Monday, Brooks’ predictions were looking plausible.

Forecasters were saying the flooding could be the worst in the history of the country.

On Sunday evening, Texas Governor Gregg Abbott said in passing that hundreds of thousands of homes could be lost.

On Monday, Federal Emergency Management Agency administrator Brock Long said he expected 450,000 to apply for federal assistance and that “the state of Texas is about to undergo one of the largest housing recovery missions the nation has ever seen.”

Brooks didn’t just call me out of the blue. For the last couple of weeks I had been working on a story about a breakthrough invention that he and his brother Richard had come up with that could revolutionize the way emergency housing could be provided following disasters like the one that was coming down in Texas.

It’s transformative, a game changer, a disruptive technology. Pick your cliché; they all apply.

They call their invention the X-Pod.

What they’ve done is re-invent the tent, the log cabin, and the Quanset hut in one fell swoop. They’ve come up with a structural concept that may be as revolutionary as the geodesic dome — and a lot more practical.

Assembled, the X-Pod is an eight-sided, 20-foot-long tube eight feet in diameter. Each Pod consists of three modules: 5-foot-long kitchen and bathroom modules attached to a 10-foot-long sleeper/dayroom module. The modules come completely wired and plumbed, with sinks, stoves, showers and johns already installed. They have storage tanks for water and sewage as well as a water filter. Each module will weigh about 600 to 800 pounds, a fully assembled Pod only a little more than a ton. The basic Pod can sleep four, and larger versions could also be produced.

The Pods are formed with box-shaped extruded tube aluminum (which resembles a hollow two-by-four) and, depending on the use, sided with anything from playground plastic to Kevlar plates. Brooks says they should last for decades.

Perhaps most important, each module will fold up into a shipping pallet no more than 2-feet high. Assembly will consist of unfolding the modules and “snapping” them together with the use of a single tool. Assembly should take no more than 15 minutes.

They can then plug into an existing electric line if one is available, or be hooked up to an emergency generator. Or they can be pre-fitted with solar panels.

Multiple pods with different interior configurations could be assembled as hospitals, schools and stores.

Brooks says the Pods are designed to be produced on an assembly line at the rate of 200 to 2,000 units per day.

As a replacement for the tent, the Pods would revolutionize the accommodation of disaster victims, refugees and soldiers. At about a ton apiece, a single flight by a 747- or C-17–sized transport plane could fly dozens of them into a disaster area or combat zone. A single ship could deliver thousands.

The X-Pod would be of obvious value in responding to the flooding in Houston and along the Texas coast, where emergency shelter is going to be needed for hundreds of thousands of people.

Too bad it was never put into production.

Here’s the thing. Brooks and Richard came up with the idea for the X-Pod in the year 2000. They have spent the last 17 years trying to get enough funding to build fully functioning prototypes that would allow them to put it into production, or at least license it to companies that could.

During that time they have talked to multiple venture capitalists, corporations, government agencies and politicians. The result is always the same: an initial display of interest, and even enthusiasm, followed by ultimate rejection.

What’s more, the X-Pod isn’t the only breakthrough invention the Fickett brothers have come up with that has had this sort of reception. They also developed a tool that revolutionizes the installation of light-gauge steel studs that are increasingly used as substitutes for two-by-fours in construction. The “Tool,” as they call it, eliminates the need for screws and can cut the amount of time needed to do framing jobs by 70 percent.

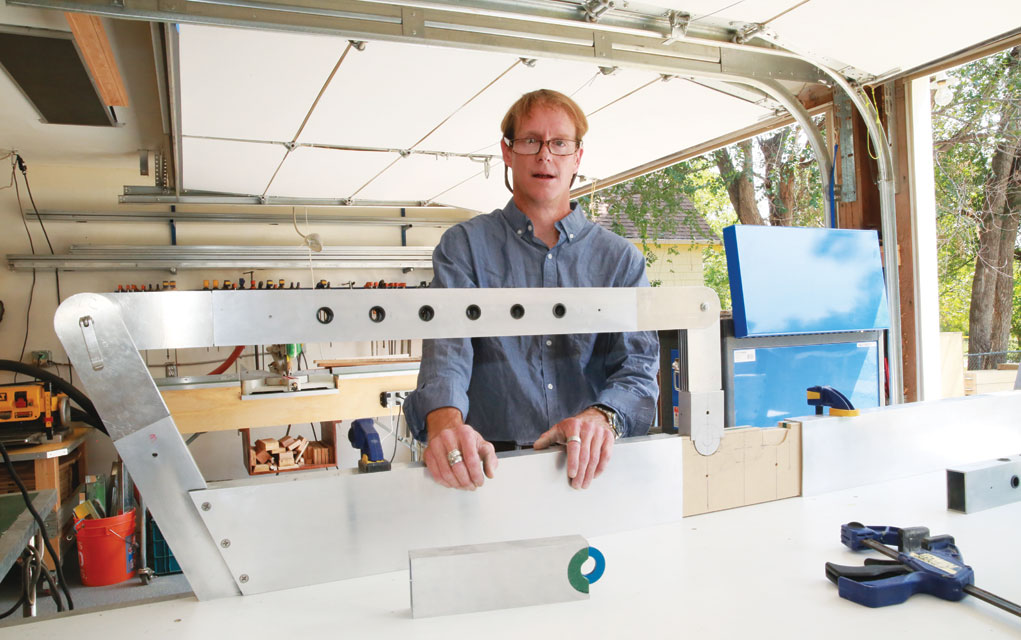

Currently, the X-Pod is little more than a paper product. Brooks has built a metal, non-folding mock up of the framing (see photo) and several examples of the folding elements. They also have machined a working fold-up scale model of a module, the sort of thing that the Patent Office used to require inventors to submit (but no longer does).

Throughout the years, Brooks and Richard have sunk whatever assets they could scrape together into keeping their projects alive. Brooks says he has gone homeless three times, sleeping in his car, “in order to make this work.”

“There’s no more real research in the world than going homeless in order to study it,” he says.

Who are these guys?

Carpenters and self-trained inventors, it turns out.

Brooks and Richard grew up in Boulder.

As they tell it, they had a magical childhood. They were raised by their father, a physicist at the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST). When the boys weren’t rampaging around town on their bikes, they seem to have had the run of the labs. The Bureau (as we called it back in the day) did a lot of research on cryogenic engineering, and as a result they had the engine from the Saturn 5 moon rocket on the premises. The boys used it as their jungle gym.

“Our father’s colleagues were some of the top government physicists,” Richard says. “Whether we were four-wheeling around the back side of Arches National Park with dad and his colleagues or we were following him through the hallways at NIST, we were shaped by men who saw the world defined by the laws of science and physics. We grew up looking at the real world that surrounds us with a scientist’s eye.”

They grew up playing with tools too.

Brooks says that when he was six his grandparents came home early from a shopping trip and to their horror discovered him playing with grandfather’s Skill saw. A couple years later his grand-dad gave it to him, with strict instructions not to tell anyone.

Like a lot of kids, the boys liked to build forts. Brooks says he built nine of them — including one in the back yard of his mother’s home in Vermont that was so substantial that it was added to her property tax bill.

The up-shot was that as they came of age they opted for carpentry over college.

And so they became contractors.

In 1995 Brooks landed a contract to frame out a restaurant on Walnut Street (now T/ACO an Urban Taqueria). The design included a round room that’s still there.

The complexity and the amount of time required for the job, as well as “the exorbitant number of screws” needed for the internal framing of the building, “made us feel that the screw system used to install light-gauge steel studs needed to change,” Richard says.

“Our thinking was ‘We’re contractors, how hard can it be to invent something?”

Their solution to the framing problem was the invention of the “Tool.” It’s a pneumatic punch that can bond a metal stud and track together by forming a small curl of metal around the punched hole.

The X-Pod grew out of a discussion Brooks and Richard had with a couple of friends in North Boulder about “economical ways to build housing using unconventional means.”

“We considered Buckminster Fuller’s philosophy and his work with the Dymaxion house, along with other ideas,” Richard says. Then the conversation turned to the most recent earthquake disasters and to how to get relief to people in the affected areas.

“We asked one another, how could we help with circumstances such as these?” he says.

Before long they formed a company, Enigma Development, which was intended to serve as an R and D company whose focus would be on mechanical invention.

Their initial project was the Tool.

“The idea was that we could sell the Tool idea to fund the research and development of the emergency housing project,” Richard says.

With the help of Boulder engineer/machinist Warren Schmelzer, a friend of Brooks who built fighting robots and who Brooks credits as co-inventor, and with the help of master Boulder machinist J.D. Ellington, they produced two prototypes for demonstration to major tool companies. They are still using those prototypes today.

The first company they tried to sell the Tool to was Porter Cable/Pentair. They had no idea how to get a foot in the door, so Brooks called up the company and pretending to be a student working on a report and asked to talk to the head engineer. It worked, and while the guy was at first confused, he quickly understood the potential of the product and set up a meeting at the company’s headquarters in Jacksonville, Tennessee.

In May 1999, they met with the engineer and other members of Porter Cable’s upper management.

“We gave our presentation, ran through our numbers that demonstrated the effect the Tool would have on the industry, and then asked for what we considered a fair price — $100 million for full buyout,” says Richard. “Suddenly, the management representatives started to turn funny colors.”

“We had set our price by breaking down how much Porter Cable made in one year on their pneumatic wood framing nail gun, and the marketing representative at the meeting confirmed that we were spot on in naming the price,” he says.

The meeting ended with the company reps expressing “tremendous interest” and Brooks and Richard getting a tour of the plant. They thought they had made sale, and expected to hear from the company in a week or two.

They didn’t. A week stretched into a month, and it became clear that while the engineer liked the product, senior management wasn’t ready to buy it. The head engineer left the company later that year, in part, according to the brothers, over its decision not to buy the tool.

In 2007, Brooks and Richard found an angel investor and tried again, this time with Robert BOSCH Tool Corporation of Mt. Prospect, Illinois. One of the meetings they had with BOSCH reps, again including the lead engineer, took place in a company building that was undergoing some remodeling work. The lead engineer asked some of the workers who were installing steel stud to watch the demonstration.

“They used the tool and were immediately impressed,” Richard says. “The meeting went on for a few hours, ending with the lead engineer saying he thought BOSCH would be most interested in the invention. For the next month and a half we waited expectantly for a response. Unfortunately, a message came back from another point in the company that they weren’t interested.”

Eventually they learned that BOSCH had a multi-million dollar deal with China “to purchase millions of screws that our Tool would remove from the industry,” he says.

And again, according to the pair, the engineer they had been talking to left the company as a result of its decision not to buy the Tool.

In July 2008, they tried to set up a meeting with a third company, but it fell through due to the start of the recession.

While this was going on, they tried to generate enough interest and funding to build a working prototype of the X-Pod.

Their timing wasn’t always the best. The first meeting they were to have was with the Army Corps of Engineers. It was scheduled for September 11, 2001. It didn’t happen.

Other attempts to raise the needed capital haven’t panned out either for a variety of reasons.

In October 2003, Brooks found a person interested in having a green house built in the shape of the X-Pod.

“We had been using steel studs to build full-scale ribs in our front yard to test our dimensions, and she had stopped by to see what we were up to,” syas Richard. “She requested three ten-foot sections, which we built in our front yard and set up in the street. The City of Boulder had a small problem with us having a thirty-foot greenhouse sitting in the street and suggested that we put it on wheels and get a license plate.

“It turned out we were building tiny houses long before the idea was to take hold of mainstream imagination,” he added.

While they couldn’t raise the capital to build a prototype, in 2006, again with the help of J.D. Ellington, they built a small scale model of the X-Pod frame that demonstrated how it would fold up. The model took three months to build. They applied for their first X-Pod patent in March 2006.

In 2010 Brooks ran into Jared Polis while he was running for Congress for the first time. Polis asked Brooks what he could do for him if he got elected. “If I call you, answer,” Brooks told him. And when Brooks called, he did.

Polis helped get Brooks in touch with FEMA, and this prompted Brooks to go through the process necessary to become a purveyor to FEMA.

Trouble was he didn’t have a product to sell to it.

So just how hard would it be to mass produce an X-Pod?

J.D. Ellington has passed away, but his sons are still running the machine shop, JDECM, and I asked them.

“Not difficult at all,” says Shane Ellington. “There’s been a lot of thought put into this thing. For a production shop this would not be difficult.”

“I think it’s gonna be something that really changes disaster relief.”

“It is shocking how long it has taken,” he added. “To have it sit there is a shame.”

Brooks and Richard are now aged 46 and 50 respectively. They have yet to quit their day jobs, but they have the optimism and the tenacity of the kid digging in a pile of horse shit, certain that there has to be a pony down there somewhere.

They’re considering trying the crowd-funding route. For once their timing might be right. Hurricane Harvey is making it abundantly clear that the old ways of providing emergency shelter are ludicrously inadequate — especially when disasters hit urban areas with populations in the millions. And the post-storm reconstruction is also going to highlight the need for the Tool. Tens of thousands of homes are going to have to be gutted and reframed — fast.

There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come, the saying goes — and there is nothing more infuriatingly frustrating than an idea that comes before its time.

After years of frustration in trying to get their inventions into production, Richard and Brooks joke that maybe they ought to stand in front of Whole Foods with a cardboard sign reading “will work for $5 million” (what they think it would take to build some working X-Pod prototypes). They may have something there. There’s a lot of money in Boulder, and who knows, maybe Jeff Bezos will spot them with one of his drones.

Anyway, if you have a spare few hundred K and want to help two of the most decent guys in Boulder change the world, or just need a house framed, e-mail them at [email protected].”