When India-administered Kashmir lost all internet and communication services in early August, Ajaz Siraj had no way of contacting his family, or friends at the Islamic Center of Boulder (ICB). For more than three weeks, he says, he was unable to get word out that he, and his wife, were OK.

“There was no way we could contact them, and they were worried here because they had no way of knowing what’s happening back there,” he says.

Siraj, a recently retired engineer and Lafayette resident of more than 20 years, was back in Kashmir with his wife in order to begin renovations on a house they own there. But their plans came to a standstill soon after they arrived.

The night before the communication blackout began, rumors circulated that the entire region would be shut down for months, that non-Kashmiris should leave and residents should stock up on supplies. The couple went out to buy groceries and found “panic on the streets,” Siraj says. “We had no idea what was happening, why this is happening.”

Sometime in the night, he says, all cellular service, internet and other communication systems were shut off. Local television stations, dominated by state-controlled media still worked, however, quickly informing everyone of India’s intentions.

The situation in Kashmir has long been contentious, as both Pakistan and India claim sovereignty. India-administered Kashmir has operated under unique partial autonomous status, as the only Muslim-majority state, since the creation of modern India following decolonization. But that all changed on Aug. 5, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) announced they were taking control of the region and cutting off all communications. It’s a move that the U.N. has said deprives Kashmiris “basic freedoms,” and many see as a move to alter the demographics of the region in favor of India’s Hindu majority.

“Kashmir has a distinct culture, a distinct language, a distinct way of life that is different from India,” Siraj says. “So that is at a huge risk right now.”

Siraj’s story is just one of many that will be discussed at An Evening with Human Rights Activists at the ICB on Friday, Jan. 17. The event will also cover the plight of Muslims in India and Eastern China.

“In China and Kashmir and India, they don’t want Muslims to be there at all,” says Tracy Smith, who converted to Islam two years ago and is a member of ICB. It all amounts to what she calls “cultural genocide,” whereby Muslims’ customs and religion — their complete way of life — are being threatened.

“Everything that they do, everything that they believe in is made illegal,” Smith says. “The Chinese government and the Indian government are attempting to eradicate entire Muslim societies.”

ICB has 23 different cultures and countries represented within its community, and the event is meant to educate them about the plight of different Muslim groups around the world. But it’s also designed for the larger Boulder County community, and the organizers welcome anyone and everyone to join.

“People in Boulder are very educated and aware of the situation in other parts of the world,” says Hadi AbdulMatin from ICB, who is helping organize the event, “but we want them to hear first-hand experience from the people who are actually impacted.”

Originally from India, AbdulMatin says his friends and family back home have seen an increase in discrimination since Prime Minister Modi and the BJP took power in 2014.

“They tell me that the situation compared to five or six years ago is different,” he says. “They are looked at suspiciously. There are also cases of verbal and physical abuse.”

In remote villages, he’s even heard of Muslims who have stopped raising cows, an animal sacred to Hindus, for fear of persecution.

“So they are changing their business line,” he says. “It’s too risky to have cows because, who knows, they may get attacked.”

The situation has escalated in the last month, as India passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, which Modi claims is an effort to combat illegal immigration and provides an easy naturalization process for Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Christians and Zoroastrians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Muslims aren’t included in the law, however, even if they are from persecuted minorities in those Muslim majority countries, or, for example, Rohingya refugees from Burma.

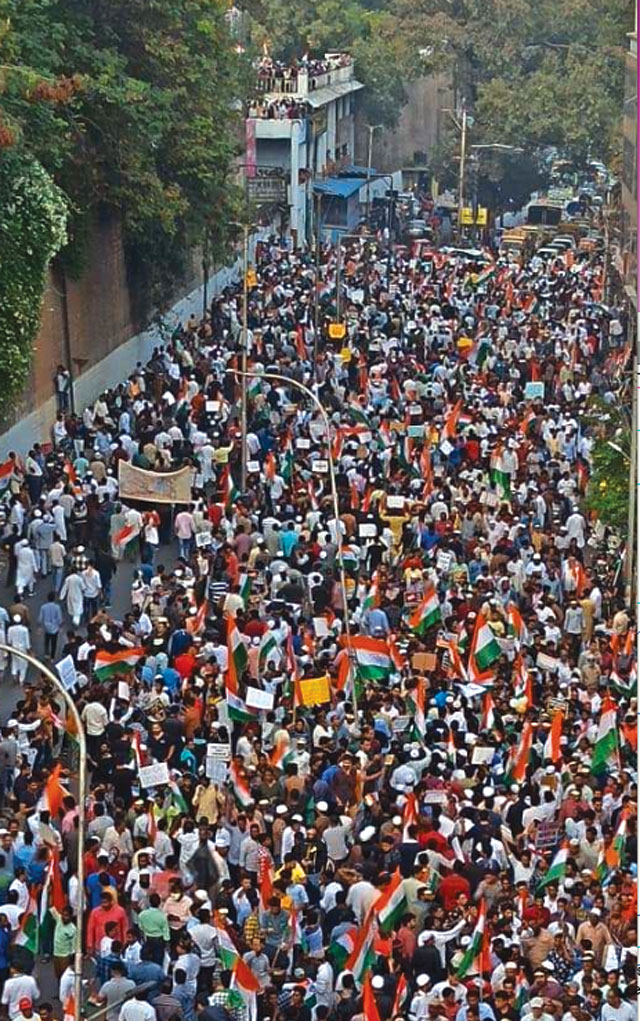

The law has brought widespread protests across the country since its passing in mid-December, as it is seen to violate an equality provision of the Indian Constitution by using religion as a basis for citizenship. Since protests began, at least five people have been killed with many more arrested and injured. According to The Economic Times, Modi, who has blamed the violence on protesters, has said, “Those creating violence can be identified by their clothes,” for many, a tell-tale sign of his Hindu nationalist agenda.

The law is also tied to a country-wide effort to document and register citizens across the country, where the burden of proof is on the individual in a country where error-free documentation is hard to come by.

“Basically, there will be millions, possibly tens of millions of Muslims who will not be able to prove their citizenship and they will be removed from citizenship roll and what will happen to them only God knows,” AbdulMatin says.

The event at the ICB will also cover the plight of Uighurs in Eastern China, although the woman speaking about that does not want to be identified for fear that the Chinese government could retaliate against her family back home. In well-documented reports from The New York Times and others, Muslim Uighurs have been taken into what the Chinese government calls “re-education centers,” although they are widely believed to be detention camps. Since 2017, an estimated 1 million Uighurs have been interned at approximately 85 camps, where many have claimed they are tortured and held against their will because of their religion. In 2017, China also passed a law prohibiting men from growing long beards and women from wearing veils as is culturally customary for Muslims around the world.

AbdulMatin says the situation in China is the most extreme, but “what India is doing in Kashmir is to change the demographics and what India is trying to do in the rest of the country is to marginalize the Muslim population primarily, but other minorities as well,” he says.

“It’s very important to allow people the freedom to practice their religion safely and move around the world and have their rights as human beings,” Smith says. “And those rights are being stripped away in violent manners around the world and in small ways, in small units, in Western countries as well.”

She sites burqa bans in France, and other policies in Europe targeting Muslim minorities. Even though religious discrimination is illegal, there are plenty of examples of it happening in the U.S. as well, she says.

“There’s hate speech, there are shootings, there’s fear. And there’s a lot of misinformation, a lot of misunderstandings, about Muslims,” Smith says. “So we really want to dispel and avoid the narrative that defines Muslims as only terrorists, extremists and separatists, because it can lead to this. I know it seems like a huge leap in this country and these things are extreme, but these things happen all over the world.”

In Kashmir, it’s been more than five months since the communication systems were shut off. In light of other world events, “People have already forgotten about what is happening in Kashmir,” Siraj says. “The people of Kashmir are still suffering but that seems to have gotten lost in all this right now.”

Businesses have shut down or have become completely cash-based as they need the internet to run credit cards and process payments, Siraj says. People have stopped sending their kids to schools, he adds, for fear of not being able to get ahold of them. There’s no way to contact help in case of an emergency and doctors can’t access health records.

“Many people are suffering because of the [lack of] internet,” he says.

He returned to Colorado several weeks after it all began, but while he was there, going out during the day was like visiting a ghost town, he says, the streets completely deserted, with the exception of government checkpoints.

“Traveling at night was very, very scary, especially because you couldn’t contact anybody if something happened,” he says.

Siraj has been able to keep in contact with some of his family through landlines and cellular phone plans. But prepaid cellular service, which comprises the majority of usage in the region, still remains shut down.

“The people [are] feeling that India completely ignored our rights,” he says. “They have proven that we are really not part of India. We are occupied by India and they can take our rights away at any time and they can treat us how they’re treating us.”

For Siraj, it’s been made worse by the fact that while he was in Kashmir he wasn’t able to pay his U.S. health insurance monthly premium, resulting in the cancellation of his plan, something he’s still trying to rectify.

Siraj hopes to return sometime this year to see family and finish the renovations. But for now, he’s committed to sharing the stories of what’s happening in Kashmir with the community of Boulder County.

“Many people think that India is a democracy, a thriving democracy. But we want to [let people know] that the narrative that India is putting out has some holes in there,” he says. “The way it is now is not a democracy. It is majoritarian country. They are passing laws without keeping the minorities in mind.”

ON THE BILL: An Evening with Human Rights Activists. 6 p.m. Friday, Jan. 17, Islamic Center of Boulder, 5495 Baseline Road, Boulder. Free and open to the public.