As I wind my way north on the narrow two-lane road, I realize Wyoming can’t be far off. I squint over the steering wheel into the hazy distance, at a cone-shaped mountain creeping over the horizon. I assume it must be Hahns Peak. I’m getting close.

This strange journey — to meet a Vietnam veteran who fought in the last battle of that terrible war, a survivor of the infamous “Mayaguez incident” of 1975 — was not one I could have anticipated coming across in the Rocky Mountains. But in this business sometimes the stories pick you. So when this tale of captured ships, island combat, terrorist freedom fighters, American hostages, Marine casualties and Cambodian luxury resorts came my way, I felt compelled to follow it down the rabbit hole.

It’s one of those tales that begins at its end, with the 2012 funeral of a Colorado Marine, Private First-Class James Joseph Jacques. Jacques died almost half a century ago, half a world away on the island of Koh Tang, on a chaotic half-baked rescue mission that ended in disaster.

Jacques’ remains were abandoned on the island during a hasty retreat, after an ugly encounter with Cambodian Khmer Rouge soldiers. Jacques, along with 12 other deceased Marines, was returned stateside in 1995, but he wasn’t laid to rest until 2012 after DNA testing finally made it possible to identify him. He had been 19 at the time of his death and would have been 56 when he was buried in Denver’s Fort Logan National Cemetery, surrounded by family members he’d never met, and his sister Deloise Guerra, who hadn’t seen him since he left for duty in October 1974 — shortly after his 18th birthday.

“We always wondered what happened to him,” Guerra told Denver’s local CBS news affiliate in 2012. “We didn’t ever lose hope that someday we would hear something.”

Jacques’ Colorado burial may have closed a chapter in American history, but it surely didn’t finish the story. While the identification of Jacques and several other previously missing in action American soldiers offered at least partial closure, there were still missing Marines who had been left behind. Some were known to have been killed in the battle, but others had been left behind alive, never to be heard from again.

There were also survivors who’d made it home — veterans who lived to tell their horrible tales, including one who lives in Colorado.

Barely.

“It’s called Hahns Peak Village. Do you know where that is?”

“Not a clue,” I told the Mayaguez Marine veteran over the phone.

“That’s OK, young man. It’s up by Steamboat. Let’s meet in the afternoon, though, so my meds have time to kick in,” he said with a chuckle.

“Good thinking,” I told him.

“Semper fi.”

A week later, I was driving almost an hour north of Steamboat, finally closing in on Hahns Peak and the small village at its base. There’s not much to this place. Nothing but a handful of houses, a roadhouse and the Hahns Peak Café, where we’d agreed to meet.

He was not hard to spot. Sitting alone at a table inside, a large green plastic box beside him, the only person in the restaurant. He stood when I entered, peering at me from beneath a green military cap pulled low over his eyes, wearing a silver dream catcher necklace, a green buttoned-down shirt and a long dangly earring hanging from one ear.

He stuck his hand out, “Radar.”

We shook hands and sat down for burgers.

Radar (aka Richard Alan Frazee) is a third-generation Marine. A gruff, tough man who spent his post-military years lumberjacking and wrestling the demons he brought back from Koh Tang. He discussed at length his disdain for the VA’s “ass-backwards” policies on providing vets disability, having been turned away by VA therapists because he was “too fucked up,” as he described it. He’s had two back surgeries, the result of his years logging, and was forced to stop working about six years ago. Now, he helps get free meals and free rides for “shut-ins” in his area — veterans who can’t drive, or who don’t leave home often — and also works on veteran suicide prevention.

We ate. I listened. We shot the shit. And all the while, I kept glancing down at that green box. I wanted to know what was in there. Something told me that box held most of — if not all — the answers to my questions.

“You drink whiskey?” he asked when our plates were empty.

“Sure do.”

“Great,” he said, standing and lifting that green box of his. “Get us a couple of double Makers straight and I’ll meet you outside.”

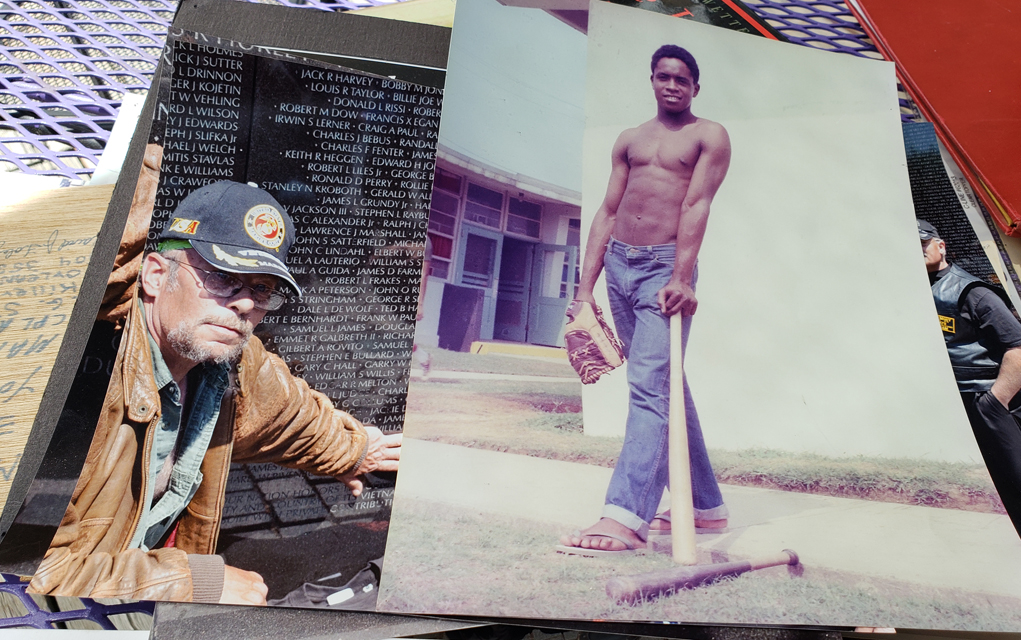

I followed orders. And when I stepped out into the afternoon sunlight, the vault was open wide. The table before Radar was completely covered in photos, documents and old keepsakes, the green box, empty. I handed him his drink and sat down.

• • • •

The day was May 15, 1975. The Vietnam War (in those parts of the world, referred to as the “American War of Aggression”) was over — or at least it was supposed to be.

A few days earlier, radical Cambodian communists, the Khmer Rouge, had seized an American cargo ship known as the S.S. Mayaguez and took its crew hostage, compelling the U.S. military to respond. The cargo ship had been seized in Cambodian territorial waters en route to Thailand, carrying a number of Americans and some 107 containers of routine cargo, 77 containers of government and military cargo, and 90 empty containers — a load insured for $5 million.

But the U.S. was already pulling out of the region, tail tucked and ill-tempered after 10 years of jungle warfare gone awry. In the government’s eyes, this hostage situation was an act of aggression that could not be tolerated, one that needed to be dealt with in order to save American lives, lost cargo and, perhaps more importantly, America’s already wounded pride.

It was decided within the white marble halls of Washington D.C. that this “rescue” mission would be the last battle of the war and it would be a face-saving, overwhelming victory.

Problem was there was no one left in the South China Sea to send to the rescue. Saigon had been evacuated two weeks earlier, the rest of the region’s forces were in rotation, and there was almost no one left to deploy. No one, except for the 2nd Battalion 9th Marines on Okinawa, including James Jacques and Radar.

These Marines were still in training. They had never seen combat.

“We were actually training in the field when they called us in and said, ‘You’re going’, and we loaded up right away,” recalls 1st Lieutenant Dan Hoffman, Radar’s lieutenant who now lives in South Carolina. Only 18 at the time, Hoffman was suddenly in charge of a battalion of men, headed into the maw of action.

According to the CIA intelligence passed down to them, Hoffman says, the Khmer Rouge were holding the Mayaguez ship, its crew and cargo hostage on a small island off the Cambodian mainland. In order to reach that island, Koh Tang, the entire assault force was going to have to be shuttled via transport helicopters and dropped off on two separate beaches.

Originally, the plan went like this: eight helicopters would swoop in on the first attack wave, landing Marines on both the east and west beaches of Koh Tang. Between those landing zones was a narrow strip of jungle where the enemy was supposed to be hiding. Upon landing, the Marines would group up and the east beach Marines would drive through the jungle, through the Khmer Rouge, into the west beach Marines, who would hold their position. They’d then link up and sweep the island together like a scythe.

The Khmer Rouge were not supposed to put up much of a fight. According to the briefing, this island, where the Mayaguez and its crew were allegedly being held, was only guarded by 15 to 20 lightly armed fishermen-pirates.

Or so they thought.

When the Marines showed up on Koh Tang promptly at 6:03 a.m. on the morning of May 15 in their big, loud and overloaded Knife-21 helicopters and attempted to land, they were met with extremely heavy machine gun fire, mortar fire and rocket-propelled grenades. The island was not only fortified, but guarded by well over 100 highly trained, battle-hardened Khmer Rouge soldiers.

“The CIA did a horrible, horrible job with the intelligence,” Hoffman says. “The island was reinforced with a Khmer Rouge infantry battalion of their Marine troops, who were specialized, and they were armed with heavy machine guns.”

Not only that, but they had heavy artillery, too. Somewhere on the island a 90mm anti-aircraft cannon was ripping holes in their helicopters like they were made of tin foil.

According to the government’s executive summary of the battle, “In the first 20 minutes of the assault, three helicopters were shot down and one sustained severe damage.”

The first helicopter landed safely on west beach and unloaded, but it took so much damage in doing so, that it lost an engine before taking off and crashed three quarters of a mile off shore. The second chopper was immediately hit so hard that it had to turn back before it even dropped off its Marines and crash landed in Utapao, Thailand.

The third helicopter went down over the water, 50 meters from east beach. Seven Marines and two Navy corpsmen were killed in the crash, three more were shot trying to approach the shore and one died in the burning wreckage of the chopper. Somewhere among them, was Jacques of Colorado, who would remain lost to the ocean for another 20 years. The other 13 Marines on that helicopter swam out to sea and were rescued by a passing Navy ship some two hours later.

Lieutenant Hoffman and his men were in helicopter number five and landed on west beach, where all remaining helicopters were forced to land. Radar describes it as a true moment of “fear and loathing.” Which Hoffman backs up: “As soon as we crouched out of the helicopter, the guy right next to me got shot,” he recalls.

Of the 180 Marines and sailors in the initial attack wave, only 109 of them had made it ashore. And they were scattered: 60 on east beach, 20 with Hoffman and Radar on west beach, and 29 more with the battalion command element isolated south of them; all pinned down by extremely disciplined marksmen, all taking extremely heavy fire. Of the original eight helicopters in the initial attack wave, three had been destroyed and four more were damaged too badly to continue on — leaving only one helicopter in working order and two more in reserve. That presented a serious problem for extraction.

But that was hardly the most pressing problem at that moment; these Marines had bigger, more immediate problems.

They had no food, no water and no idea how they were supposed to proceed. The plan had instantly gone to pot and now they were stuck in a situation that was further imploding by the minute.

As luck would have it, though, Radar and Hoffman had landed right near a Khmer Rouge supply depot, full of grenades. They hunkered down behind the thatched walls of that sanctuary, lobbing grenades into the enemy-populated jungle and returning fire whenever they could. During the skirmish, Radar recalls running out from under cover to save a Marine who’d been injured on the beach. He sprinted out, bullets flying past and picked up his brother in arms.

“He was stumbling and non-equilibrium, dizzy and all that, and I was trying to get him to run,” Radar says. As they were making their way back to cover, a Khmer Rouge mortar landed right next to them, blowing both men off their feet, straight into the latrine — an open pit of human waste that had been baking in the sun, likely for days. “It was everywhere, it was in my mouth, my ears, my nose, my eyes. … And all I could think was, ‘I’m not going to die covered in Gook shit.’”

After they were pulled to safety, out of “the crapper,” Radar waded straight out into the ocean. Right in the middle of that firefight he stripped naked and washed himself off.

“I got wrote up for that,” Radar recalls, shaking his head. “For ‘blatantly endangering government property,’ they said. But I didn’t care.”

Hours went by, as Lieutenant Hoffman and Radar organized air strikes from the supply depot, Radar operating the radio (earning him his nickname) and communicating with the other Marines spread across that island.

Around noon, a full four hours into the assault, the Marines had managed to piece together a plan over the radio. Lieutenant Hoffman was going to lead what he would later call a “posit assault squad” to try and link up with their command element, which was isolated some 1,000 meters to the south of their position on west beach.

Radar went with, as did their mutual friend and Marine brother Lance Corporal Ashton P. Loney and eight other Marines.

“That was when I went from being a boy to being a man,” Radar says, staring into the distance.

The jungle was far too dense to move through covertly. Instead, these young Marines clung to the shoreline, speaking in hand signals and navigating the rocky terrain. At the same time, the command element was moving toward them from the south. The two groups were to meet up right in the middle, but they found a bunker between them, occupied by Khmer Rouge soldiers.

“I had one grenade,” Hoffman recalls. He and his men crawled right up under the bunker, as stealthily as possible and simultaneously, on Hoffman’s order, threw their grenades inside. The bombs detonated and before the dust had settled, the Marines charged.

Hoffman and his men cleared that bunker, discovering a cache of machine guns, mortars and the troublesome 90mm anti-aircraft cannon that had been making it so difficult for their helicopters.

It was a daring plan in an otherwise chaotic mission, one that earned Hoffman the Bronze Star.

But it also came at a great price. Loney was killed at some point during the skirmish. Radar recalls following the man who he believed had killed Loney, chasing him out of the bunker, through the jungle in what he described as a “fugue state.” Radar can’t remember how long he chased that man, but when he finally caught up to him he wasn’t in a mood for mercy.

“I emptied my clip into him when he stopped,” Radar recalls, a glassy, red look in his eyes. “I cut that motherfucker in half.”

Loney’s death still clearly haunts Radar, and Lieutenant Hoffman as well. The squad wrapped Loney’s body in a poncho and carried him, along with the Khmer Rouge weapons, back to the west beach and the other Marines waiting for them at the supply depot.

It was part victory parade, part funeral procession.

Toward dusk, at 6:23 p.m. a U.S. plane flew by and released a strange-looking object over the enemy territory. It wasn’t an encased bomb, but a palate, and it looked like supplies. The Marines feared the worst. Everyone thought that the Air Force had just delivered the enemy all the supplies they so desperately needed.

But that wasn’t the case.

“In fact, it was a huge, 15,000-pound BLU-82 daisy cutter bomb that actually knocked people off their feet,” Hoffman says. “It was the largest non-nuclear weapon in the U.S. arsenal at the time.”

According to Hoffman, things on the island went deadly still for a while after that cataclysmic boom.

It’s worth taking a moment here to consider just how intensely grim and miscalculated this entire mission was from the start.

The ship that these Marines had been sent to rescue, the S.S. Mayaguez and its crew, wasn’t even on Koh Tang. It never had been. It had been on another island the entire time. And at 6:07 a.m. (four minutes after Hoffman, Radar, Jacques and Loney had descended upon Koh Tang) the Cambodian propaganda minister released a statement:

“Regarding the Mayaguez ship. We have no intention of detaining it permanently and we have no desire to stage provocations. We only wanted to know the reason for its coming and to warn it against violating our waters again.”

This whole operation, all the blundering and bloodshed, all the lives lost, all of it was unnecessary from the get-go. By 10:05 a.m. the Mayaguez crew had been secured, the ship was safe and its cargo, accounted for.

By 10:05 a.m. the Marines on Koh Tang had already been under fire for three hours. They were stuck there in the heat of combat, trying desperately to figure out how they were going to escape alive.

Not long after that unexpected BLU-82 Daisy Cutter dropped, Hoffman says, “The decision was finally made, we were going to try and get out of there before nightfall.”

But that was going to be no easy feat. As the executive summary points out, “With the decision to extract, the forces at Koh Tang began to execute one of the toughest tactical scenarios: a helicopter extraction in the midst of intense enemy fire during darkness.”

The U.S.S. Holt, which had earlier towed the SS Mayaguez into international waters, had finally arrived and positioned itself to support west beach, providing cover fire for the extraction helicopters flying in from the U.S.S. Coral Sea.

As twilight settled over the island, the tide began to move in. Where Marines once stood on sand and solid ground they were now waist-deep in water, wading out to overloaded helicopters, as green enemy tracer rounds screamed past.

Hoffman got on the second to last chopper out, Radar on the very last. He didn’t want to leave his Marine brothers’ bodies there, he says, least of all Loney’s. “I was the last guy off that island,” Radar says. “I almost didn’t make it. We were getting overwhelmed, and it was very dark.”

Radar’s helicopter landed on the U.S.S. Coral Sea, so badly damaged it was on fire, Radar says. It nearly blew up with him inside, as he recalls, but a sergeant pulled him out at the last second. “[He] reached over through the machine gun square window, grabbed me, pulled me out, and when I laid down under the helicopter, it blew up.”

Radar was safe. He was alive. Which was more than many of his fellow soldiers could say. And for his bravery he would receive the “Valor Under Fire” medal.

Hoffman’s helicopter made an insane and incredible landing on a moving ship, only five minutes after he was picked up. The pilot put the Marines down on a flight deck that was too small to land on. He had to hover the tail over the water while holding the front end over the deck of the bobbing, lilting ship.

“It was the most amazing feat of flying I’ve ever seen or heard of,” Hoffman says.

When it was all over, 15 Americans died in action on Koh Tang and 23 more in helicopters en route to the island — among them, Jacques and Loney. Jacques’ remains wouldn’t be identified for another 37 years. Loney’s remains have never been recovered.

There were also three Marines left behind in the chaos of the extraction, “missing in action and presumed dead” the executive summary reads. Lance Corporal Joseph Hargrove, Private First Class Gary L. Hall, and Private First Class Danny Marshall had been on west beach, and protecting a flank of the perimeter when the last rescue helicopter took off leaving them for dead.

Hargrove was captured the next day and executed on the spot. Hall and Marshall became prisoners of war, never to be seen or heard from again.

“The story that we were told at the time was that they had to have been killed during the extraction,” Hoffman recalls. “And so we just moved along our merry way.”

Years later when the terrible truth finally came to light, both Radar and Hoffman said they experienced severe PTSD. It’s something that has tormented them ever since.

“The last 41 names on the [Vietnam Veterans Memorial] Wall are from Koh Tang,” says Hoffman. “And that’s very special to us.”

Every year Hoffman, along with at least some of the surviving Mayaguez veterans, gather in Washington D.C. for a reunion at that Wall. They convene to remember, to pay their respects, to cry together for those who died.

“It’s very cathartic,” says Hoffman, emotionally. “When you share it with your brothers who were there with you, it’s extremely meaningful.”

Each reunion, fewer and fewer of the Mayaguez veterans show up; their group grows smaller by the year. But those who are able to make the journey keep going back, seeking closure they may never find.

Their story is far from over. There are still American Marines over there, whose bodies have never been returned, and the clock is ticking on whether or not they ever will be. A Cambodian real estate company World Land Bridge has purchased Koh Tang and plans on developing it as a luxury resort — complete with hotels, restaurants, dive shops and bungalows. What was once a hellacious, blood-stained historic battleground may someday soon become a vacation destination. And whatever bodies might still be over there, will be lost to history forever.