— It’s tempting to think of college campuses as islands of

enlightenment, places where students embrace new ideas, people and

cultures without the specter of hate hanging overhead.

Tempting. But it’s not always the case, as demonstrated by events on campuses across the nation in recent months.

There were cotton balls scattered outside the black cultural center at

To be sure, such events have always been part of the

American landscape. But campus and diversity experts say they’ve seen a

surge in the past year, poking yet another hole in what increasingly

appears to be the myth of a post-racial America.

“I guarantee that any given campus in the nation will have small incidents like these in a given year,” said

But Cole and others see a correlation between a rise

in campus hate crimes and the increasingly nasty exchanges taking place

among our nation’s politicians and leaders — on both sides of the

political spectrum. It would be naive, they say, to not expect that

discord to show up on campuses.

The nation’s first black presidency, he said, has simply provided “kindling for the fire.”

It’s difficult to know just how much hate crime is occurring on college campuses.

data suggest that 12 percent of hate crimes occur on either college or

school campuses. The numbers aren’t broken down to show how much of it

happens at universities. And experts say many instances of racial or

sexual slurs are never reported.

Even so, they say incidents reported in the news and through their own professional organizations point to a pattern.

“At least anecdotally, there seems to have been an increase. But we don’t know for certain because reporting is so bad,” said

A search for examples need go no further than

which has witnessed a series of incidents in recent months. Racial

slurs have been found scrawled on walls or shouted at black students. A

student in early February reported being threatened with lynching

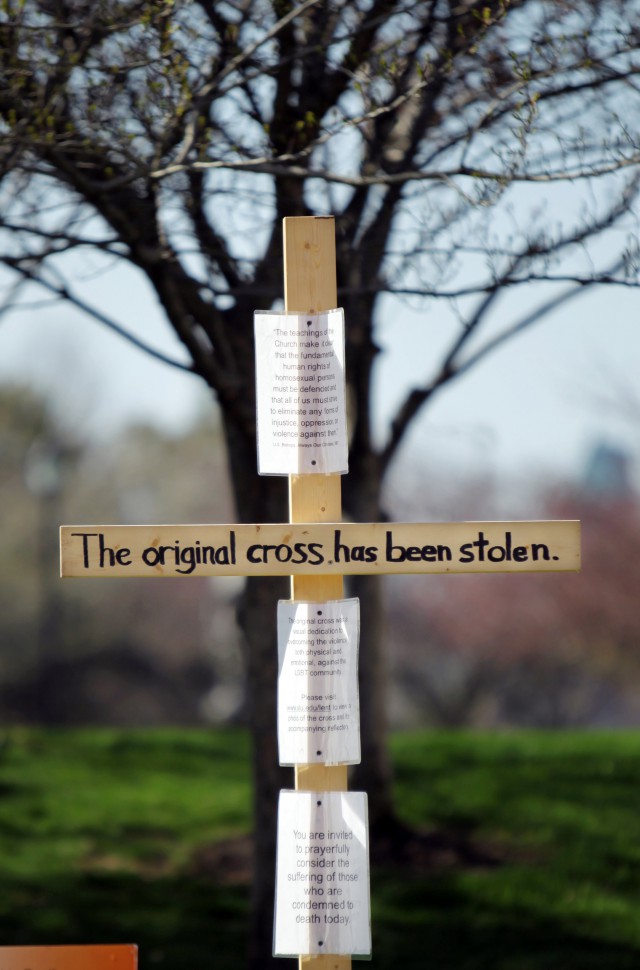

during a confrontation with another student. And a cross belonging to a

support group for gays and lesbians was stolen.

University investigations have resulted in

punishments handed down in two incidents, but officials say privacy

laws restrict how much they can say.

“All I can tell you is that two of the students who were involved are no longer enrolled at the university,” said

Of course, not every incident with racial overtones

rises to the level of hate crime. But even the lesser transgressions

can cause hurt feelings and, for some students, doubts about their

future on the campus.

Such was the case for

a freshman at SLU who learned earlier this year of a Facebook group for

members of her dorm floor. Among the discussion threads on the social

networking site was a post about things overheard on the floor:

“There’s nothing I hate more than black people,” it said.

The comment was later deleted. And several people

involved apologized to her in writing. But the damage was done: “I

thought we were all really close. But then to see their true feelings.

It made me feel really uncomfortable.”

In some ways, racial or hate-driven episodes can

push a campus closer together. At SLU, for example, students and

administrators have rallied in support of the targeted groups with town

hall meetings, gatherings, diversity forums and a “We Are All

Billikens” campaign, asking students to sign a diversity pledge and

wear a wristband.

The university’s president, the Rev.

And while some find reason for hope in the

community’s reaction, many say they know there is only so much that can

be done to influence long-held prejudices.

“I wouldn’t say they are really changing anyone’s views,” said

Still, some students want more from administrators.

Officials recently received a form-letter e-mail from more than 120

students with a list of demands, including: the establishment of a

24-hour hot line to assist students who’ve been threatened; a

campus-wide e-mail alert system to let everyone know when an incident

has occurred and a requirement that all students take a social justice

class.

“They hear us, but I don’t see any action taking place,” said Ono Oghre-Ikanone, president of the

Porterfield said administrators are reviewing the

demands and that many of many will be addressed. But he urged students

to give administrators time: “Sometimes the process takes longer than

some people would like it to.”

One of the more frustrating aspects of these

incidents, from a college administrator’s viewpoint, is the fact that

colleges are composed of students with a wide range of backgrounds.

“Sometimes people think of college campuses as these

isolated and protected environments, when in fact they are a microcosm

of our broader society,” said

The

when two white students scattered cotton balls outside the

Gaines/Oldham Black Culture Center. The students were arrested and

suspended.

As was the case at SLU — and virtually every other

campus where such events have happened — the incident was followed by

calls for unity. There was a daylong event organized by students, along

with a town hall meeting attended by top university officials.

That the community rallied in support of black students has done a lot to keep emotions in check, said

a sophomore from O’Fallon, Ill., and member of the Legion of Black

Collegians. “It didn’t just affect the black students on campus,”

Taylor said. “We were all embarrassed that this would happen on our

campus.”

said campus dynamics are further complicated by students of different

backgrounds not always understanding one another and how painful their

actions might be.

“I do think a lot of white America doesn’t

understand that you can’t play around with things like ‘lynching,’ ”

Brown said. “There’s just no humor in that.”

———

(c) 2010, St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Visit the

Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.