It was a clear January day when the fire inspector arrived at the Sacred Tribe’s cultivation facility in Denver. The inspection had been scheduled mutually between the city and the building’s occupant to ensure everything was up to city safety codes: to check exits and signage, inspect the emergency lighting—the usual routine. However, the inspector was almost immediately confronted with a scene that shocked them.

Within the building was a state-of-the-art psychedelic mushroom grow operation and extract laboratory, growing more than 31 different strains of the Schedule I fungi and in large enough quantities to supply several hundred people. Perhaps naturally, the fire inspector thought they’d stumbled into an illegal drug operation—albeit a very clean, safe and casual one.

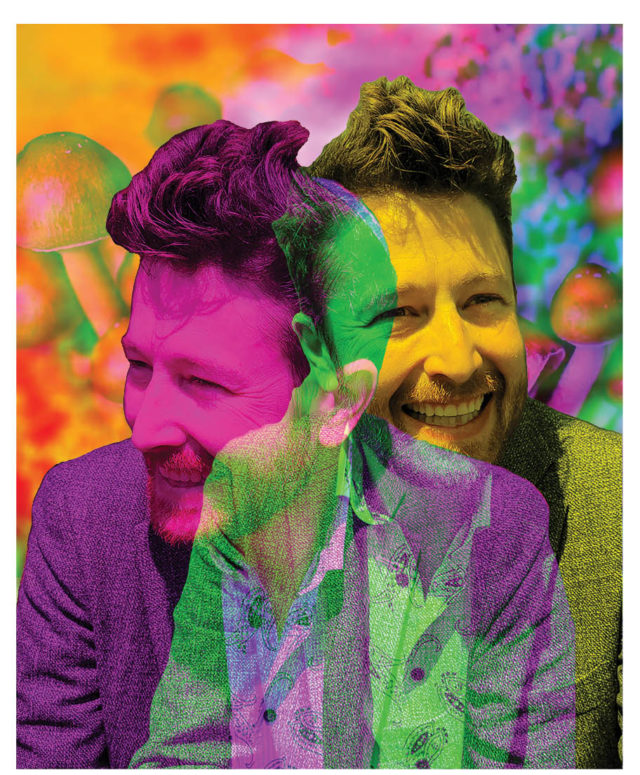

The inspector called the police, and within hours officers in tactical gear, wielding assault rifles and a search warrant, were busting through the front door. They arrested the chemist who was on site and issued an arrest warrant for Rabbi Ben Gorelick, the founder and leader of the Sacred Tribe congregation in Denver. Gorelick turned himself in just a few weeks later and was charged with first-degree felony possession with intent to manufacture or distribute a controlled substance.

“One of the biggest stones that somebody will inevitably throw [at this story] is, ‘Why didn’t you just wait until November to do all of these things?’” Gorelick muses, referencing a possible upcoming ballot initiative that would legalize possession of almost all naturally occurring Schedule I controlled psychedelics.

“And the answer to that question is, I didn’t need to [wait] … [psychedelics] have been part of religious practices for millennia. And in this country we have already decided that Schedule I controlled substances—psychedelics, mushrooms, etcetera—absolutely deserve protection as part of a religious and ceremonial practice,” Gorelick says. “We’ve had laws on the books [for decades] exempting [religious] psychedelic controlled substance use.”

The Sacred Tribe is not like other synagogues you’ll find in Denver. For one, its members are not all Jewish and in fact come from a variety of denominations, backgrounds and spiritual beliefs.

Second, its school of spiritual thought is deeply rooted in kabbalah, an esoteric discipline in Jewish mysticism, so old it’s traditionally understood to extend back to Eden, before written history. Gorelick describes kabbalah as an exploration of feeling states in which the goal is to “feel the largest possible human emotional spectrum without guilt or shame or repression,” he says. If you feel angry, bitter, sad, dazed or confused, don’t turn your back on those feelings, kabbalah teaches. Feel those emotional sensations as deeply as you can; then, Gorelick says, it’s easier to transform them into something “positive”—and if you’re feeling happy, excited, hopeful or gay, explore and expand that feeling as much as you can. It’s an interrogation of your values, your feeling states and of your character.

“It’s a very somatic and a very heartfelt experience of spirituality,” Gorelick says. An experience that the nearly 300 members of the Sacred Tribe enhance with breathwork practices, dance and, of course, psychedelic mushrooms.

When the tribe gathers for its sacrament ceremonies (which have been temporarily paused since the raid and Gorelick’s arrest), it’s a full weekend-long experience. All members have to apply and go through a preliminary medical screening first. Then, Gorelick explains, they’ll have dinner on Friday, to get to know each other, get comfortable with each other, breaking bread over conversation. The following Saturday evening they’ll gather and imbibe the mushroom sacrament together, “dropping in.”

“The goal isn’t to blast people off to the moon,” Gorelick says. People choose how much they want to take, but it’s usually less than one to two grams. “The goal is [to achieve] that blurring of the line between self and community and God.”

In a past life, Gorelick was a chemical engineering student, and while it wasn’t a career path he chose to pursue, he’s applied that knowledge and mindset to his work with mushrooms. He casually talks about the 15 different alkaloids mushrooms contain and how some cross the blood-brain barrier and others don’t; how he surveys the Tribe’s members on their somatic experiences with each of the 31 different strains they utilize. They extract those mushroom alkaloids in their lab with a proprietary process and then, prior to each sacrament ceremony, members set an intention and based on that, Gorelick and the member will select a strain (or combination) to help achieve that intention most effectively.

“Every strain is so radically different with its intention,” he says. Some strains are great for heart opening and offer euphoric feelings akin to MDMA, while other strains are better for dropping into a deeply spiritual space, and still others are best used for cleaning the slate and emptying oneself entirely.

While it might seem radical and new-agey for a contemporary synagogue with a hip-rabbi to so earnestly and openly use psychedelics to connect on a deeper level with God, community and self, it isn’t. Gorelick explains that there’s at least a 2,300-year history of Jewish sacramental use of psychedelics.

“Psychedelics are something that is deeply rooted in Judaism,” he says, adding that, more generally, psychedelics have been used by different religions around the world for millennia. Islam has hashish. Hinduism had soma. The Greek mystery religions had kykeon. The Native and Meso-Americans had mescaline cactuses, salvia, and psilocybin mushrooms. And the Jews?

“Mushrooms are kind of the Jewish psychedelic,” Gorelick says. Though, “we obviously have access to many more strains now than Judaism had access to once upon a time.”

This connection between religion and psychedelics is a big reason why the U.S. has certain protections for religious groups that use controlled substances in ceremony. When President Richard Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, it made it illegal for Native Americans to practice ancestral religions that involved peyote consumption. That resulted in a slew of regulatory, statutory and judicial exemptions over the next several decades that paved the way (in some circumstances) for members of the Native American Church to consume peyote without breaking the law—or, more accurately, to break the law with the DEA’s permission.

In 1993, Congress almost unanimously passed the Religious Freedoms Restoration Act (RFRA) that was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. That federal bill is a complicated one, but at its core, it’s meant to ensure “that interests in religious freedom are protected.” While intended to apply at the federal, state and local levels, in 1997 the Supreme Court case City of Borne vs. Flores ruled that the RFRA only applies at the federal level, and not to states or jurisdictions within them.

Subsequently, 21 states have passed their own RFRAs—and, notably, Colorado isn’t one of them. While Gorelick says this state has historically been supportive of religious exemptions for drug use, it isn’t specifically protected by a state RFRA here.

Which leaves Gorelick and the Sacred Tribe drifting in a legal gray area. Especially considering that in Denver—where Gorelick has been charged with possession with intent to distribute—psychedelic mushrooms have been decriminalized since 2019. Yes, Gorelick was in possession of mushrooms (lots of them), but he never had any intention of selling those, he says. The Sacred Tribe operates on a donations-only basis and no one leaves with samples.

“Most of our members don’t pay a nickel,” he says. “We don’t sell, we don’t allow people to take [mushrooms] back home. It is a sacrament. It is a religious ceremony.”

To muddy these strange waters even more, several Colorado groups are pushing different ballot initiatives that would decriminalize or legalize mushrooms and other psychedelics throughout the state (Weed Between the Lines, “Choosing how to heal,” March 17, 2022). One of them, Ballot Initiative 58, “Access to natural medicine,” would allow adults over 21 to possess, cultivate, gift, and deliver psilocybin, psilocyn, ibogaine, mescaline, and dimenthyltryptamine (DMT) legally, anywhere in Colorado.

Should Initiative 58 get enough petition signatures to end up on the ballot, and should it then pass, Colorado’s Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) will be charged with developing rules for therapeutic psychedelics programs for adults to receive treatment from a trained facilitator at a licensed facility. And Gorelick’s case will only gain more strength—even though, he says, the Sacred Tribe doesn’t really fall under the categories of use Initiative 58 aims to protect.

“I think most people think of mushrooms in like one or two spaces,” Gorelick says. “They just think of mushrooms in the recreational space—which is a space that is like 40 or 50 years old, and they’re great in that space—and we’re getting to this place now where we are going through a cultural awakening around the medical, therapeutic opportunities that exist in psychedelics as well.”

But, he says, his church isn’t either of those things. He isn’t just trying to offer people a good time at a Dead & Company concert, nor is he trying to heal their traumas or mend deep psychic wounds (though that might happen as a side-effect).

“Sacred Tribe is not a medical therapeutic healing center. It is a place where people come to explore the edges of what’s possible,” he says. “We’re doing God’s work … some would call it healing work, some would call it growth work.”

Whatever you want to call it, the Sacred Tribe’s work falls outside of the recreational space and outside of the medicinal space, Gorelick says. It’s within its own tier of psychedelic use—spiritual use—and it seems to frustrate him that he’s staring down serious felony charges for facilitating that. He calls it “nonsensical.”

Daniel McQueen founded the Center for Medicinal Mindfulness, a psychedelic therapy clinic in Boulder. Speaking from the perspective of a therapist working in the psychedelic realm, he completely agrees with Gorelick on that point. McQueen says of the four types of psychedelic use—psychological (for mental health), celebratory (for recreation), scientific inquiry (for problem solving), and spirituality—spiritual use is by far the oldest and most established form.

“Trying to strip religious or spiritual use is not viable,” Mcqueen says. “[These] incongruities in the laws are not helpful and need to be challenged.”

“The structure that Colorado is setting up right now needs to include a space for this religious framework, this religious structure [for psychedelics],” Gorelick says. “This is where the real juice is … this is the heart of what psychedelics mean … are we willing to open our hearts, bodies, minds, eyes, and legal systems and structures to that infinitude of possibilities, rather than this very, very narrow box?”

(He adds that everyone should go vote yes on Initiative 58 should it end up on the ballot this fall. He just wants the state and the psychedelic advocates and activists helping to craft its legislation to consider this third leg of the psychedelic platform as they carve a path for decriminalization and/or legalization.)

Despite the serious criminal charges Gorelick is facing, he seems genuinely confident that the state isn’t going to try and make an example out of him. In fact, he’s giving his persecutors the benefit of the doubt.

“I think [the state] is trying to figure out how to be supportive of the work that we’re doing, while also not creating a slippery slope,” he says. There’s a fine (if definitive) line between a Jewish mushroom church and a “flying spaghetti monster church that does heroin,” he quips.

Nevertheless, his case is an important one that’s carrying a weight even Gorelick in all his confidence can’t ignore. Whatever happens to him will set a precedent for any and every church or religious group that imbibes psychedelics as sacrament in Colorado—from ayahuasca centers to Native American Churches and the International Church of Cannabis.

“If we decriminalize psychedelics at a personal [and medicinal] level but felonize them at a spiritual level, what does that mean for spiritual leaders?” he asks. “Of all the things that could be felonized in this country,” he says, this isn’t one of them. “Religious use of psychedelics should be utterly celebrated.”

We need to start talking about psychedelics in the religious contexts alongside these other ones, Gorelick says.

“Even if religion isn’t your bag, this is a beautiful opportunity,” he says. “We don’t need to push that underground.”

***

If you’re interested in helping Rabbi Ben Gorelick’s cause (or contributing to his legal fees) you can find both his change.org petition and his gofundme online.

Contact the author at [email protected]