Michael Denslow is a scientist who lives in unincorporated East Boulder County. For years, he thought his work in biodiversity was helping move the needle forward on addressing the climate crisis. But, as scientific research implored immediate action, he became frustrated with the lack of progress from policy makers, specifically in Colorado, with its booming oil and gas industries and talk-but-no-action Democratic governors.

Then Extraction Oil & Gas sent him a letter asking to lease the mineral rights under his property.

“You worry about what’s happening in your backyard, but at the end of the day you think about the world we want to live in,” Denslow says. “Sure, I don’t want a new fracking site in my backyard, but I recognize what we need to do is transition away from fossils fuels.”

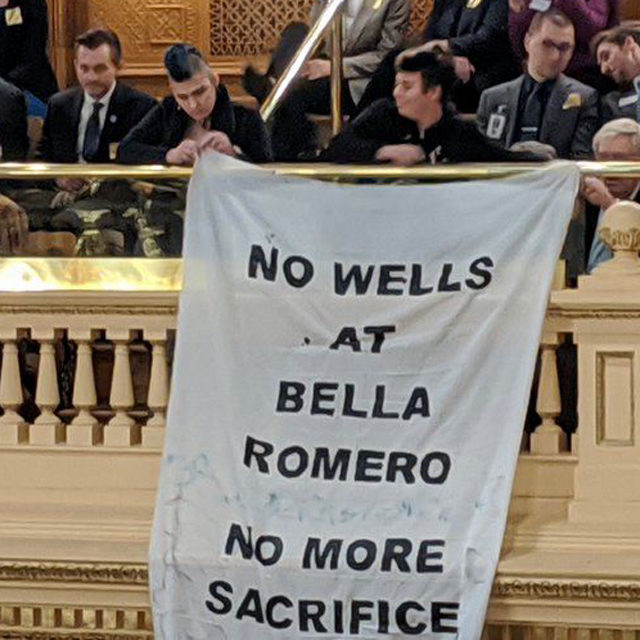

So Denslow joined the Boulder chapter of Extinction Rebellion (XR). On Jan. 9, 37 XR and other activists were arrested after a demonstration in the state house before Governor Jared Polis’ annual State of the State address. Several protestors unfurled a banner calling attention to the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission’s (COGCC) decision to allow drilling next to Bella Romero Academy, a school of 90% non-white students; a decision made worse in the eyes of social and environmental activists by the fact that the drilling was originally intended to be done near another school with a mostly white student body.

“Bella Romero is the world in a raindrop,” says fellow XR member and Boulder resident Devon Reynolds. “You can look at this one case and see the way climate across the globe is impacting people of color, people who don’t have a lot of money or people who are excluded by power systems.”

Both Reynolds and Denslow say the demonstration was meant to call attention to action that can be taken, right now, on a local level. Protestors tried to communicate three demands: 1) Shut down drilling at Bella Romero; 2) Declare a state of emergency with regards to the climate crisis; and 3) End fossil fuel extraction in 2025.

“We were trying to speak directly to the governor,” Denslow says. “This seems to be missed by the press. … This was not directed at the legislature; these were things we felt [Polis] could do something about.”

“I think Governor Polis talks a great game that is friendly to everyone, but I don’t think we have that option anymore,” Reynolds adds. “Governor Polis would like to solve climate change by mostly providing subsidies for renewable energy and making sure infrastructure exists for electric cars. That’s amazing and necessary, but market solutions are not going to solve inequality. … You have to have regulations with teeth to make sure there are consequences for polluting the general resources, like air, water and climate.”

Fellow activist Deborah Kay Kelly, who helped support and make arrangements for those arrested, agrees: For all the positive talk of addressing the climate crisis, Colorado can, and needs to, do more.

“I think Polis’ climate plan has a lot of merit but we don’t have enough inspections and we don’t have broad enough setbacks and we don’t have a moratorium on more drilling, and perhaps he was unable to achieve that, but we would like him to be standing up for it a lot more,” Kelly says.

It is politically convenient to talk about addressing the climate crisis in broad terms or to provide timelines that new administrations can push back or that begin after it’s too late to make necessary adjustments, Denslow adds. Objectively good news like Tri-State closing its Colorado and New Mexico coal plants should not distract from what XR sees is an immediate need to ban fossil fuel extraction in the state.

“We’re a huge producer [of fossil fuels in Colorado], and we’ve had record production under Hickenlooper, Polis, under these Democratic polticians,” Denslow says. “So the question really becomes, what are we doing now, and our concern is that politicians are always trying to do something that doesn’t put too much on them — talking about 2040, 2050, that’s something far enough in the future they don’t have to take immediate consequences for that, and our corner is asking you to do something immediately that can help propel us and be a model.”

Reynolds adds that addressing fossil fuel extraction is one thing, but there needs to be a holistic social change in order to ensure future communities aren’t abused.

“If we solve sustainability or energy sustainability without figuring out the unjust ways that these systems affect people, then we’re just going to end up with some other problem, some other issue, whether it’s food scarcity, these things just keep revolving,” Reynolds says.

“All these politicians [showed up] to Martin Luther King Day events… how do you think Martin Luther King would see the situation at Bella Romero?” Denslow asks. “Climate change and civil rights are different issues, but think about someone like him and what he stood for, which is what we’re supposed to be celebrating. I wonder what he would say about what’s happening there. I wonder what he would ask them to do.”

The protest gained national attention when Bernie Sanders tweeted his support for XR and Sunshine Movement (a youth climate-advocacy group) on Jan. 10. Wrote Sanders, who stumped for Polis in 2018: “Young people are showing the courage to lead the fight against a climate disaster when many of our leaders won’t lift a finger. They do not deserve to be arrested — they deserve to be applauded and heard.”

Reynolds says the positive attention that comes with Sanders’ support outweighs any cynical concerns it’s a politically expedient time for the candidate to push progressive values.

“It matters for this to be a national conversation,” Reynolds says of the tweet. “It matters that people understand what’s happening in Colorado.”

“I think its mostly another step toward making people more aware,” Kelly adds. “To me personally it feels like some kind of a validation or a victory.”

Many of the 38 activists were charged with trespassing, disruption of a public assembly and/or obstructing a peace officer. Denslow says the group can’t divulge when the next act of civil disobedience may occur, but their focus will be on forcing change in Colorado and in Boulder County, where, as he knows well, efforts to frack are already underway.

Correction: A previous version of this story indicated Denslow and Kelly were arrested during the protest; they were not.