“If you’ve come here to help me, you’re wasting your time. But if you come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let’s work together.” — Lila Watson, aboriginal activist

It was 9 a.m. on a Saturday morning, and the church parking lot was already filling up. It was January, but still warm enough that a young couple rode up on their bikes, towing a toddler in a trailer. A volunteer with a name tag opened the locked door for each person as they arrived. Dozens of people were gathering for another round of volunteer training at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Boulder (UUCB), where Ingrid Encalada Latorre has been in sanctuary since Dec. 16, 2017.

On that day, in the middle of flu season, Ingrid wasn’t feeling well. She introduced herself, via an interpreter, giving a brief summary of her journey since leaving Peru in 2000, including a felony charge for using falsified documents in 2010 and the failed attempts to appeal her conviction in both 2016 and 2017. To make matters worse, her partner, Eliseo Juardo Fernandez, was being held in detention at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) contract facility in Aurora, and she was in the middle of planning vigils and press events in an effort to get him released on bond.

She seemed exhausted.

As members of UUCB’s Sanctuary Now ministry started their training, Ingrid sat onstage looking out at the full pews. Her youngest son, Anibal, 2, sat on her lap, while her oldest, Bryant, 9, leaned on her shoulder. She didn’t last long before excusing herself to her room to get some rest before the community potluck that followed the training. She thanked everyone for their support before leaving.

“Our perfection is challenged in this situation,” Mary Dineen from UUCB told the crowd. “We can have a tendency to try and fix this. A) we can’t and B) we shouldn’t. This is Ingrid’s journey.”

Since first entering sanctuary in November 2016 at the Mountain View Friends Society in Denver, Ingrid has become an outspoken activist, advocating for broad immigration reforms that could help not only her, but tens of thousands of other immigrants as well. She has, sometimes reluctantly, put herself in the spotlight in her effort to draw attention to what she believes is the systemic injustice of the U.S. immigration system.

“Just like we are doing things outside our comfort zone that we know are the right things to do so we do them anyways, I think that’s what she’s doing,” Mary Jo Highland, volunteer coordinator and Ingrid’s interpreter told me a few weeks later. “She knows it’s the right thing to do for her community. She might not be as public if it were 100 percent up to her and there weren’t other people depending on her.”

At the same time Ingrid is serving her community, she finds herself dependent on hundreds of local volunteers from more than a dozen different faith congregations and the broader Boulder County community in order for her to take sanctuary. As the group of new volunteers soon learned, sanctuary is an enormous undertaking. What started as half a dozen UUCB members meeting to discuss books about immigration in 2011 has become a massive volunteer operation.

A religious exercise

Spearheaded by Dineen and Jenny Fitt-Peaster, the immigration ministry at UUCB began with education. In addition to book discussions, they hosted cultural events, held vigils at the ICE detention facility and organized a trip to Arizona, where they walked through the desert and saw scattered shoes, empty water bottles and crosses marking the graves of immigrants who died trying to make it into the U.S. With the desire to be immigrant led, the group also intentionally connected with the immigrant community in Boulder.

“This congregation has been doing a lot of work for a number of years to not [fall into] the white savior complex,” says Reverend Kelly Dignan. “How do we come alongside those who are oppressed and not do it out of charity but out of solidarity?”

Mercedes García has lived in Boulder for more than two decades, and at the time UUCB was developing its sanctuary ministry in 2011, her husband was in deportation proceedings, leaving García to raise three daughters alone.

“The ladies [from UUCB] would come and help keep me calm,” she says. “It’s really difficult for people who aren’t in your actual shoes to understand what’s going on. But they were a great, big help. I was afraid to tell people what was going on but they helped me feel safe.”

UUCB welcomed García into their community, inviting her to share her story and ask for help when she needed it. She sold tamales, burritos and flan to the congregation to help make ends meet, and the church invited her to work in childcare on Sunday mornings during services, which she continues to do every week.

It’s been a difficult journey for García since her husband was deported. One of her daughters has had a particularly rough time, experiencing deep states of depression, causing her to fall behind in school and often not want to leave the house. But through it all García has felt supported by the UUCB community.

“When you are in a situation like this, it can be really easy for people to judge you or throw dirt on you,” she says. “But to have open communication between people is really important in feeling supported. When we’re all supported, we’re stronger together.”

There are three families from the church in particular, García says, that she knows she can call whenever she needs help. Likewise, church members, many who are elderly, have called on her to assist them after surgeries or injuries. “It feels really good to have that sense of mutual help where they know they are helping me but I also feel like I am actually helping them too,” she says.

UUCB also became a founding member of the Denver Metro Sanctuary Coalition, which has supported several host congregations and immigrants in sanctuary since 2014, when Arturo Hernandez Garcia became the first person in the modern movement to take sanctuary in Colorado, spending nine months at First Unitarian Society in Denver.

“These were really important steps in being able to eventually become a sanctuary church,” Fitt-Peaster says. “It really helped us be ready when the need for sanctuary arose.”

By January 2017, it became apparent that more and more people might need sanctuary as the political climate grew increasingly hostile toward undocumented immigrants. UUCB helped form the Boulder County Sanctuary Coalition with several other area churches, and the group began discussing the need for a host congregation in Boulder County.

“Historically the church has been a place of sanctuary. We’re in a long line of wonderful people,” says Harriott Quin, a member of the sanctuary coalition representing Community United Church of Christ (UCC) in South Boulder. The congregation recently and unanimously adopted a resolution in support of the Boulder County Sanctuary Coalition at its annual meeting.

“It is a core teaching of both the Hebrew scriptures and the New Testament, that we are to welcome the stranger, welcome the alien and, in the Hebrew scriptures, treat them as citizens of the land,” Lee Berg, interim minister at Community UCC explains. “The very fact that we call the places of our worship sanctuary implies that this is where people can feel safe.”

When it comes to more modern history, churches around the country offered sanctuary to people fleeing deportation during an immigration crackdown on undocumented migrants from Central America in the 1980s, but the approach then was very different than it is today. Ministers and other church members would host immigrants in churches or their homes for brief periods of time, often without the knowledge of the congregation. While several current members of UUCB acknowledged their church took part, no one could provide much detail, as the entire operation was conducted in secret.

“That was clandestine,” says Fred Cole, a member of UUCB for 50 years and one of the original members of the current immigration ministry. “This is intentionally very open what we’re doing.”

Protected by an ICE directive that discourages, but doesn’t prohibit, immigration enforcement in sensitive locations such as churches, the current sanctuary movement informs ICE when a church is, as they say, “hosting a sanctuary guest.”

“The one thing that faith communities can do that not many other communities can is offer sanctuary. This is part of our religious duty, our religious exercise,” Dignan says. “As long as a church doesn’t harbor or transport, there’s nothing illegal about what we’re doing.”

Still, in-line with the structure of Unitarian Universalism, she didn’t want to make a top-down decision about becoming a host congregation.

“We’re a spiritual community, so discernment is different than a regular old democratic process. Discernment comes from the same root word as discussion. Not debate but discussion,” Dignan told the congregation in spring 2017. “So we’re going to have heartfelt, soulful, discussions about this for four months and every person is going to have a chance to be in that discussion.”

During the process of discernment, Dineen, Fitt-Peaster and others hosted all church forums and met with every single group and committee in the church. Most of the concerns centered around security and legal risks, not about whether or not it was the right thing to do.“It wasn’t so much the moral issue as the concerns about the legality, about safety, about did we have enough space or would we lose enough income that we wouldn’t be able to continue,” Fitt-Peaster says. In response, the immigration ministry brought in immigration lawyers and the Sheriff’s Department to answer questions. They also started a pre-sign up sheet for volunteers from other congregations in the Boulder County Sanctuary Coalition to ensure the congregation that they wouldn’t be in this alone.

Their efforts paid off and on Oct. 29, 2017, the congregation overwhelmingly agreed to be a sanctuary church for undocumented immigrants.

“It makes me really proud to be able to say my church was the first sanctuary [in Boulder,]” García says. “It means a lot to have a community that will not only listen to you but support you when you share your story.”

The decision was not without risk, however. The vote wasn’t unanimous and Dignan says the congregation lost four members that she knows of for political reasons. Plus, shortly after the vote, a preschool that had been renting half of UUCB’s building shut down, leaving the church with a $35,000 shortfall for the remainder of the fiscal year.

In Dignan’s sermon the Sunday after the vote, she told her congregation they were up to the challenge. “I’ve been watching, and you’re ready,” she said. “This is not going to be precise or orderly. It’s going to be chaotic, we’re going to feel like we’re out of control. Things will not be perfect. And that will be our chance to grow.”

Dignan says the action of becoming a sanctuary is in line with the Unitarian Universalist tenets of faith, where every person has inherent worth and dignity. “When the rubber meets the road, are we willing to put our own self at risk and inconvenience and maybe financial impact to offer courageous love to the world and to honor all people?” she questions. “[Another tenet] is that we are all connected so that when one strand of the web of life is torn the rest of us feel it and the rest of us are called to repair that strand. We’re a network of mutuality, we’re tied together in a garment of destiny. … Our liberation is bound up with one another.”

With this in mind, church members immediately began preparing space to host someone in need of sanctuary. They installed security cameras, did maintenance work and started training volunteers. They cleared out an archives storage room and music room, and set up the space with a donated bed, microwave, mini-fridge and TV. They hooked up a hose with a shower head at the end of it to the faucet in the nearby men’s bathroom, which already had a drain in the floor, while making plans to convert one of the stalls to a proper shower. They also trained volunteers for various duties and started a sign-up sheet for specific shifts. By the end of November, everything was ready. The only remaining question: Who would come?

Welcoming Ingrid

“It was kind of like having a baby,” Dineen says. “You knew it was going to come but you didn’t know who or when.”

On Saturday, Dec. 16, Fitt-Peaster and Dineen were at a Christmas party together, when around 8 p.m. they got the call that Ingrid and Anibal would be arriving in Boulder from Fort Collins soon. The two left their partners and their friends and hurried over to the church.

They already knew of Ingrid, who had been at the Foothills Unitarian Universalist Church in Fort Collins for almost two months, since the day she skipped out on her deportation flight and claimed sanctuary. “I fell into step with them really quickly and fell in love with them,” says Ingrid about the Fort Collins congregation. “I felt bad, because I couldn’t say goodbye to my friends and volunteers there because it was a secret that I was leaving.”

As difficult as it was to leave, she was looking forward to being closer to her family in Westminster and the immigration activist community she had built in Denver. Friends could more easily visit. The move also meant her partner of eight years, Eliseo, could join her when he got off work in the evenings. He is stepfather to Bryant and father to Anibal.

“I feel really good that they’re here with the support and that they’re here safely,” says Eliseo. “It’s much better having them here with me in the United States then if I were here alone.”

With all this in mind, Ingrid packed up her belongings that Saturday night and drove herself to Boulder, where she was welcomed by the entire congregation the next morning at Sunday service.

It wasn’t long before the resilience of the community was tested. Just a couple weeks after Ingrid took up residence at UUCB, she received an emergency alert from Eliseo. Several hours later, Ingrid learned that he had been picked up by ICE on his way to the grocery store and was being held in the immigration detention center in Aurora.

“We already knew that one day ICE would come to get me because of her (Ingrid). So we always had a plan. We always knew it was going to come,” says Eliseo, who has been in the U.S. for 16 years. “But still they told me it wasn’t because of her; it was because I was a criminal. But it’s not true, and we all know it’s not true because I’m just here living simply.”

ICE has admitted the agency learned about Eliseo while investigating Ingrid, but maintains they did not arrest him as retaliation for Ingrid’s stay in sanctuary.

After hearing about his detention, UUCB and sanctuary coalition immediately mobilized behind Ingrid, as she and his parents attempted to get him released on bond.

“It made me feel a lot better that she wasn’t alone while I was locked up, and for her to have the support meant a lot,” Eliseo says. As a response to his detention, supporters held weekly vigils outside of the Aurora ICE facility, and more and more volunteers signed up to help at UUCB.

It takes a village

After four training sessions, there are now approximately 200 volunteers committed to helping Ingrid in one capacity or another. In addition to grocery shopping, doing laundry off-site and providing childcare, someone has to watch the doors at all hours of the day, every day of the week. UUCB has been organizing volunteers into four three-hour shifts throughout each day, along with a 12-hour shift overnight.

The door monitors are trained on who to contact in case of an emergency, and how to interact with ICE officers if they come to the door. But mostly they sit under a sign that says “welcome table,” reading, playing games with Anibal and Bryant, and talking to countless people coming and going from the church.

“I underestimated the amount of work and effort it takes. On the other hand, it brings together your congregation in ways you probably didn’t anticipate,” says Larry Dansky, member of First Congregational Church UCC on Pine Street which participates in the Boulder County Sanctuary Coalition.

“They may be doing this for Ingrid and because it’s the right thing to do and all of that, [but] it’s maybe the best thing this congregation has done for bringing together a community,” he says during a recent door shift. “I think there’s always a benefit to the struggle.”

The Boulder County Sanctuary Coalition now has a total of 13 congregations from around the County, all of which contribute time, resources and volunteers to the sanctuary effort.

“There is absolutely no way we could be a sanctuary church without the other churches,” Dignan confesses.

Member congregations take up special offerings for UUCB’s preschool fund, which helps supplement the church’s operations while they search for new tenants to take the place of the former preschool. They organize monthly community events at UUCB, giving Ingrid the chance to socialize. They volunteer to help her with English, or lead an exercise class she can participate in or take Anibal to preschool, where he’s still so young he needs an adult with him at all times.

While time-consuming, it is proving a rewarding experience for volunteers.

“It’s a way of acting out my faith,” says Laura Terpenning, a retired pediatrician and member of Community UCC. “Plus, I’m still doing something for kids.”

It took a little bit for Anibal to warm up to Terpenning, and he often asked for his mom when she first started taking him to school or storytime at the library. But now when she comes, he confidently puts on a small backpack and marches out the church’s doors, leaving his mother to her life inside.

“The first couple of weeks, it was hard,” says Ingrid about sending Anibal to school with someone else. “But there’s not much he can do here and it’s good for him to be with other kids.”

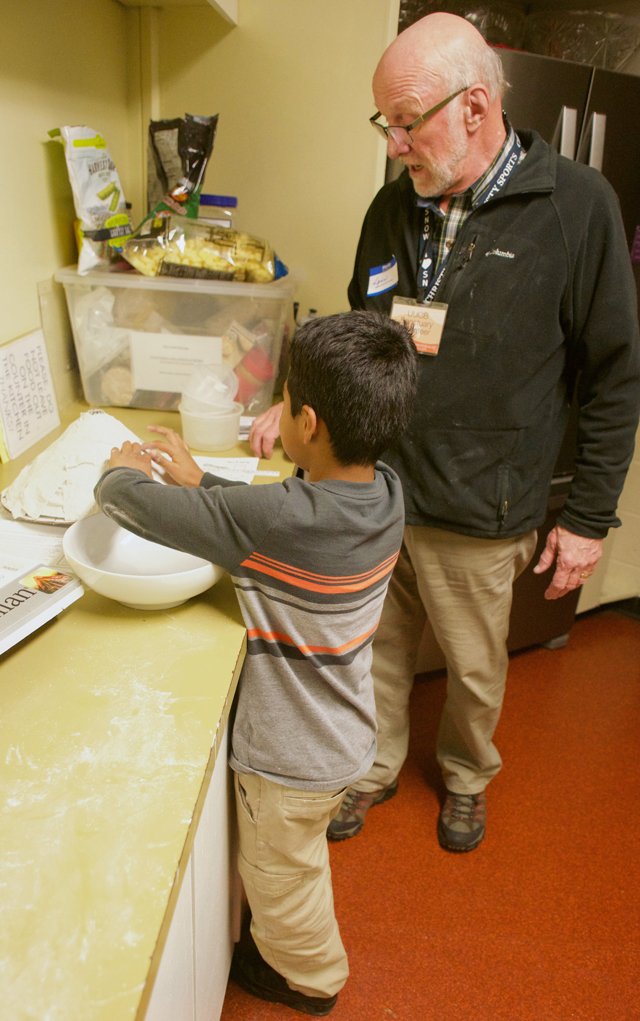

“One of the perks of the job,” says volunteer Barbara Richards, is getting to interact with Anibal and Bryant. Like many of the volunteers, she often plays marbles, checkers and cars with the boys as she sits at the welcome table. On a recent evening shift, volunteer Lynn Johnson helped Bryant make an exploding volcano from a science kit he had been given. The two took over the kitchen while meticulously constructing the plaster mountain.

“What I do is the easy part. I just show up and open the door. I’m not a planner or an organizer. I didn’t think up the idea,” says Johnson, who lives in the neighborhood and is also a member at First Congregational Church. When he first heard Ingrid and the boys had moved into UUCB, he was inspired to help, motivated by federal policies and rhetoric.

“It’s simple: pushback,” he says.

Many members compared this experience to being involved in social movements like women’s suffrage, the civil rights movement or the underground railroad. “This is what we need to stand up now for,” Dineen says. “It’s easy to look back and say, ‘Oh, I would have helped them,’ but this is what it looks like to be involved or be active now.”

A new normal

Ingrid has now been at UUCB for almost four months. It’s been six months since she’s been back to her apartment in Westminster, where Eliseo, who was released from ICE custody after posting bond in early February, still resides.

“A house is where you eat and you sleep,” Ingrid says. “Right now I consider this (UUCB) my house.”

There are challenges to raising kids in a church, she admits. They all live in one small room with an even smaller closet. For the first few months they took bucket showers in the men’s bathroom by boiling hot water. It was really stressful, and the bathroom often flooded into her room. Building the shower took longer than expected, and was just recently finished through the help of volunteers, including former Denver sanctuary seeker Arturo Hernandez Garcia, who came up in the evenings after work to tile the bathroom.

Having a shower has made things significantly easier, Ingrid says. Still, there are often activities during the evenings and it’s difficult to keep her kids on a consistent schedule. Almost every night Eliseo drives up to Boulder to help put the kids to bed and see her.

“Just like anyone who works a long day, I just want to go home and relax but then I’m alone,” he says. “So I want to come here.” His next scheduled ICE check-in isn’t until September 2019, but “it doesn’t feel that long,” he says.

Despite the challenges, the family feels safe at UUCB, grateful they are all together.

“We’ve gotten into a rhythm of life, somewhat,” Ingrid says.

Her favorite thing to do is take her kids to the church’s playground, enclosed by a fence that protects her from ICE. She says she enjoys the views and breathing in the fresh air, but it’s also challenging, a harsh reminder of the freedom she no longer has.

“I see people, running for example, and it makes me sad because I can’t do it,” she says. “I used to run a lot but now I’m here and I can’t do it anymore.”

She’s rarely bored, she says, and it certainly appears she has a lot going on despite her confined circumstances. Once a month, she attends the Boulder County Sanctuary Coalition meetings, where she shares with the faith communities about her life, her needs and her plans. She meets with organizers from around the state, like Jeanette Vizguerra, who drew national attention during her sanctuary stay in Denver last year. Plus, there are a variety of activities taking place at the church every day.

“There’s a lot of groups that come through and I try to involve myself with most of them, not necessarily to talk about immigration, but to do things like the gardening or music,” Ingrid says.

She’s working on her English and computer skills and recently applied for a grant to start college classes. She dreams of being a lawyer to help other immigrants who find themselves in similar situations. With little legal recourse at this point, she is committed to the sanctuary cause, calling for broad policy changes from inside UUCB.

While there’s nothing easy about being in sanctuary, Ingrid takes comfort in the fact that there’s always someone to talk to and she enjoys spending time each day sitting at the welcome table with volunteers, trying to learn all of their names, exchanging stories and laughing together.

“I think I’d rather not even call them volunteers and just call them friends,” she says. “Because they are always here for me.”