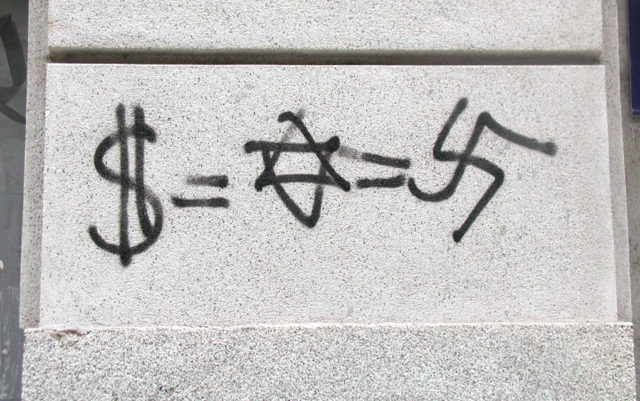

Last week, residents of Longmont awoke to discover their neighborhood defaced with offensive graffiti: four red swastikas painted over other graffiti on a resident’s backyard fence. It was the second such vandalism in two weeks in the town of 90,000. Officials worked with the fence owner to paint over the Nazi-related symbols.

Without suspects, the motivation behind the swastikas in Longmont are unknown. However, recent years have seen growing hostility and violence against minority faiths, including those in the Jewish community, reports the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) in their annual Audit of Anti-Semitic Incidents. The 2015 study shows that national incidents rose 3 percent from 2014, which saw a 21 percent increase from the prior year. The news comes after a steady 10-year decline following a hate crime spike post-September 11.

According to Scott Levin, regional director for the ADL in Colorado, the escalation makes sense given the emerging global interracial and interreligious tensions and the current state of public affairs in the U.S., which has the second-largest Jewish population in the world.

“It’s attributable to hateful rhetoric in politics these days,” Levin says. “If you’re talking about how ‘horrible’ the immigrants are or people from certain countries, that emboldens people to use the same sort of hateful rhetoric when describing anyone they don’t agree with.”

In 2015, there were 941 reports of anti-Semitic crimes in the U.S. including verbal threats and physical violence. People were shot with paintballs or hit with rocks. Synagogues received prank calls and suspicious packages. A building at Yale University was defaced with the statement “Yale is a Jew hole — let’s round them up,” and someone painted swastikas on a Jewish fraternity building at Vanderbilt University.

In Colorado, reported numbers increased almost two-fold from 2014 to 2015, going from 10 to 18. There were 15 cases identified as threats or other harassment, two cases of vandalism and one report of physical assault.

This current wave of anti-Semitism is being expressed in more passive and indirect forms than in the past, with most reports of hate crimes involving defacement of property or verbal harassment, according to the most recent FBI Hate Crime Statistics. But the motives for these actions are rooted in the same ideologies as they’ve always been.

“People hold these deep-seeded beliefs that it’s easier to blame the ‘other,’” Levin says.

Often referred to as “the longest hatred,” anti-Semitism goes back to the founding of Judaism and its followers have been the source of scapegoatism for societal issues throughout history. Negative Jewish archetypes were utilized centuries before Hitler and the rise of Nazism in Europe, and can be seen today with conflicts like those in Gaza and with ISIS.

Samuel Boyd, assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Colorado Boulder says Jews have long been a convenient scapegoat. He points out that even in ancient times, aristocrats upset over economic issues would often blame Jews for the problem because it was an easy way to divert attention.

“So when there was economic or political insecurity,” he says, “they became the targets of accusations and attacks. Today the markets are far from stable, and we see a rehashing of rhetoric.”

Boyd mentions a phrase used in PBS documentary Story of the Jews: “The Jewish imagination is paranoia, confirmed by history.” He says when there is discontent, Jewish people usually become the object of prejudice, so their fear is constantly validated.

However, a big step toward feeling secure is community support. Jonathan Lev, executive director of the Boulder Jewish Community Center, says solace helped heal apprehensions last year after the center received an envelope with a threatening note, prompting a large police presence and investigation.

“A core element of what defines Boulder is people actually care about one another,” Lev says. “After this incident hundreds of people throughout the community — people not associated with us, government officials — reached out to show their support. The response was ensuring people continue to feel safe and comfortable and at home at this space they connect with deeply.”

He has spoken with hundreds of families about the incident since, and while the organization tries to look forward, there is a responsibility for education.

“Hatred, whether towards one group or another, needs to be both identified and reported by everyone when a specific community is affected by it,” Lev says.

The ADL was formed in 1913 with a mission of confronting anti-Semitism and has since moved toward combating discrimination in general, while also tracking global attitudes toward Jewish people. A planet-wide survey reveals more than a billion people harbor anti-Semitic beliefs. These perceptions are most prevalent in the Middle East, Europe and northern Africa.

And while these numbers are shocking, they are most likely much higher. Overt bigotry is not accepted the same as it was, say, 100 years ago, but current politics are testing that.

Rabbi Jamie Korngold, from Boulder’s Adventure Rabbi program, agrees recent discourse is to blame.

“I think it’s the general rhetoric in society today,” she says. “The incidents of hate crimes have risen in the past year because it’s become more acceptable to speak and act negative towards people different than you.“

Many incidents, Korngold says, are quietly reported to the police and don’t make the news, in order to try to minimize copycat attacks. The ADL’s press release even generated repercussions, she says, although cannot go into detail for safety reasons.

Levin says that the victims of these crimes might not report them at all, for varying reasons. “Sometimes the targets of hateful action are embarrassed; they don’t want to draw attention.”

However, it seems the general consensus is that anti-Semitism in the U.S. needs to be both talked about and addressed. In 2004, Congress passed the Global Anti-Semitism Review Act, which created a committee to research hateful beliefs toward Jews. Of the legislative effort, then-president George W. Bush said, “We have a duty to expose and confront anti-Semitism wherever it is found.”

“We very much, as an organization, encourage people to report and make it known,” Levin concludes. “It’s only by tracking, identifying and bringing these occurrences to light that we can deal with it.”