creative at Rockstar Games pauses for 10 seconds. “It’s America,” he

finally replies. “The birth of modern America. What was gained and what

was lost.”

Some might scoff at the idea that a video game can

tackle such heady themes, but Houser and his brother Sam, the

co-founders of Rockstar, are used to being underestimated. Their label,

part of Take-Two Interactive, is best known for its massively popular

Grand Theft Auto series, which has sold more than 100 million copies

and generated lawsuits, boycotts and legislation because of explicit

violence and sexual content.

The Housers are British immigrants whose critical

eye for their adopted country and embrace of its pop culture tropes is

reflected in nearly every game they make. Recent Grand Theft Auto

(known affectionately as GTA) releases fit comfortably in the tradition

of crime dramas like “The Godfather” and “Scarface” with plots that

comment on the myths and realities of the American dream.

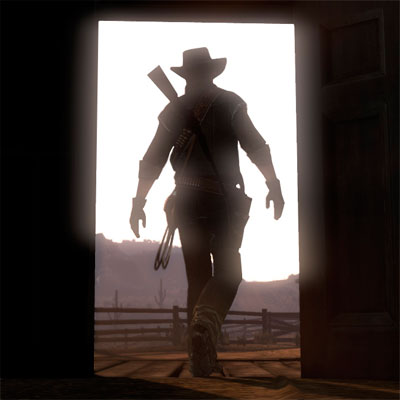

Now Rockstar is moving into perhaps the only genre

that provides an even better backdrop for those themes: the Western.

Red Dead Redemption, which comes out

years of development, takes place at the twilight of the Old West, in

1908, when Easterners and automobiles were encroaching on the

previously untamed frontier and the cowboy was fading into fiction. The

game’s main character,

Red Dead Redemption comes at an awkward time for the Western, as the genre has been all but dead on the big screen since

The minds at Rockstar are convinced that what the

Western needs now is to be experienced instead of watched. The company

is known for making “open world” games in which players can go anywhere

and do nearly anything, and Red Dead Redemption is its biggest yet. Its

map spans from a virtual

“They’re called Westerns, not ‘outlaw’ or ‘cowboy’ films, and that’s an inherently geographical word,” said

a fast-talker with a shaved head who cites “The Wild Bunch” and 2005’s

little-seen Australian film “The Proposition” as inspirations. “One

thing games do better than any other media is give you a sense of

place. This is what we consider doing a Western properly.”

Since its founding 12 years ago, Rockstar has tried

to create a major hit besides GTA but has managed only modest success.

The substantial resources invested into Red Dead show the company

believes it can buck history and sell at least several million units at

“Rockstar has a very odd place in the industry

because there’s an audience who appreciates the way its games criticize

our culture and there’s an audience who just love running around and

blowing things up,” said

upcoming book “Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter.” “I think the first

group will love to see Rockstar explore the mythology of the Old West,

but it’s hard to know if the second will find that as interesting.”

Although Houser thinks big picture at Rockstar’s headquarters in

On the main production floor, about 200 programmers,

designers and artists were hard at work last month in their cubicles

putting the finishing touches on Redemption. It’s a spiritual successor

to 2004’s smaller scale Red Dead Revolver, which bears only a little of

the Rockstar touch because it was primarily overseen by Japanese

publisher

Roughly 500 people around the world have contributed

to Redemption over the last five years. By contrast, Activision’s Call

of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, the best-selling game of 2009, was made by

fewer than 100 people in two years.

In an office off the production floor,

success: They’re bugs that have been individually identified and fixed.

Some are huge, like characters walking through walls; others are as

seemingly trivial as the size of the moon and the color of dust.

Benzies, the president of Rockstar’s

six months ago in part to bring a perfectionist’s eye to the end of

production. “It’s vitally important that every little thing in the

world is right,” he said, “because the slightest thing that’s wrong can

disconnect players.”

It hasn’t been an easy five years, insiders admit,

with several journeys down paths never finished. It’s difficult to

imagine the final product being much bigger, however, as it takes at

least 40 hours for a single person to complete and hundreds more for

those who pursue optional challenges and play together online.

Because Red Dead Redemption takes place in desolate,

rough country, integrating a hallmark trait of Rockstar’s past games —

the ability to chance upon interesting people and things to do — was a

major challenge. “It would have been contrived to say ‘Here’s another

small town and another small town,'” said producer

“So we made the natural world alive with bears, coyotes, cougars and

snakes. It gives you that sense of struggle against the wilderness.”

There were numerous other problems inherent in a

Western setting. How do you make things stand out in a world where the

ground, the clothing and many skin tones are brown? Tricks with

lighting and smoke. How do you make objects appear rugged and

sun-warped? Forbid the use of straight lines. How do you make a horse

move as realistically as a car in Grand Theft Auto? Record a real horse

in a motion capture studio.

As with all of Rockstar’s open world games, Red Dead

is divided into missions, specific tasks that advance the story in

small chunks, such as earning a sheriff’s trust by helping him bring in

the local “most wanted.” Marston is just as deadly with his rifle as

GTA protagonists have been with semiautomatics. He doesn’t, however,

engage in any of their controversial sexual behavior. “I’m a married

man,” Marston says early in the game when told about available “female

company.”

“We have just over 500 characters who all have names, family members and jobs,” said

The least defined character in the game, in fact, may be

Though he has an overarching goal, players define what kind of man he

is and what kind of game Red Dead Redemption is based on how they

handle the thousands of interactive moments that make it up. In one

optional mission, Marston finds a woman being held up at gunpoint along

the side of the road. He can save her, participate in the robbery and

pocket the money, or ignore her and ride off into the sunset.

“The morally ambiguous cowboy is the perfect

protagonist for the style of game we make,” observed Houser. “Sometimes

you can be the hero, sometimes you can be the bad guy, and sometimes

while you’re deciding what to do, a bear comes out of nowhere and eats

someone.”

———

(c) 2010, Los Angeles Times.

Visit the Los Angeles Times on the Internet at http://www.latimes.com/

Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.