As appearances of impropriety among certain Boulder City Council members and city staff have continued to pile up in recent months, it turns out that the city actually does have mechanisms through which council members can disclose possible conflicts of interest and recuse themselves from votes that affect their property.

The question is whether they are availing themselves of those mechanisms.

Boulder Weekly has been taking a look at disclosure forms filed by city council, and has uncovered that at least two members, George Karakehian and Ken Wilson, did not sufficiently disclose the properties in which they have ownership interests. The discovery raises questions about how often council members are voting on matters that affect their private interests or those of their business partners, versus recusing themselves.

The city’s code of conduct, outlined in Chapter 2-7 of the Boulder Revised Code (www.colocode.com/boulder2/chapter2-7.htm) discusses how to handle such conflicts of interest. For instance, it says that any city council member, appointed board member or city employee “who determines that his or her actions may cause an appearance of impropriety” should consider disclosing that and recusing oneself — but is not required to — in several circumstances, including:

• “If the person has a close friend with a substantial interest in any transaction with the city, and the council member, appointee, or employee believes that the friendship would prevent such person from acting impartially with regard to the particular transaction;”

• “If the person has an interest in any transaction with the city that is personal or private in nature that would cause a reasonable person in the community to question the objectivity of the city council member, employee, or appointee to a city board, or commission;”

• “If the person owns or leases real property within six hundred feet from a parcel of property that is the subject of a transaction with the City upon which he or she must make a decision, and is not required to receive official notice of a quasi-judicial action of the City.”

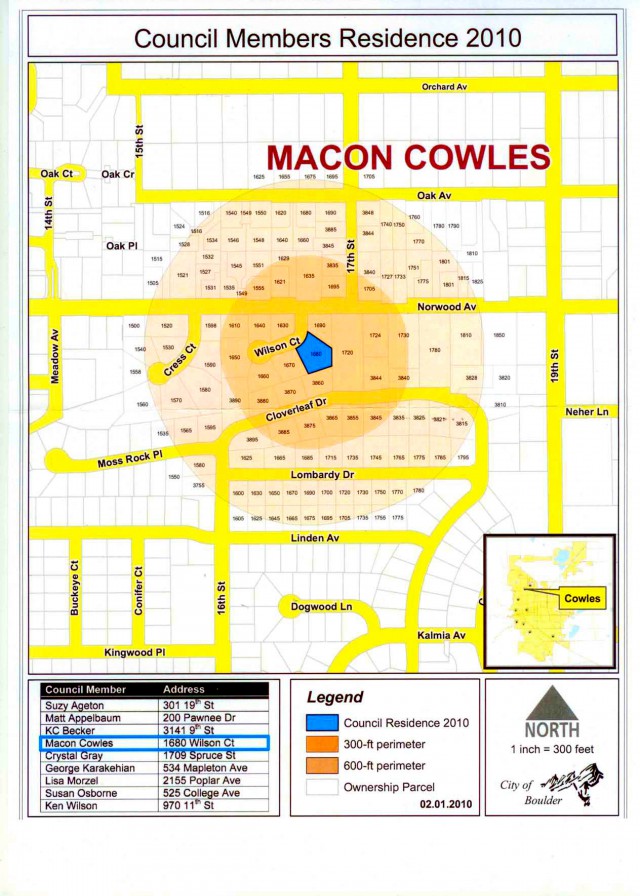

Regarding the latter provision, city staff have even sent Boulder City Council members maps showing properties they have declared ownership of, with a circle around each displaying the 600-foot radius. The idea was to encourage council members to consider recusing themselves when a decision has to be made on a property within that circle.

However, as former city council member Crystal Gray points out, “the map is only as good as the information you provide on your forms.”

Gray says members of council were only sent one map showing circles around only the property they own, not properties owned by other council members, so it’s largely a self-policing system. Since her home is downtown, she says there were several instances while she was on council when she had to double-check the distance between her house and downtown projects that came before council. In addition, Gray says, the late Tom Eldridge, who owned downtown property while he was on city council, often consulted with the city attorney about whether to recuse himself on certain votes.

City spokesperson Sarah Huntley told BW that a previous city attorney appears to have been providing the maps to council members as a courtesy, as “helpful guideposts.” She added that the city is not required to produce them for council, and it seems they haven’t been distributed since 2010.

“There was no conscious decision to not do them anymore,” she said.

But after BW requested copies of the maps for current city council members, Huntley said she was having the city’s planning department produce them this week for the council and BW.

Huntley also confirmed that the maps did not include addresses of commercial or rental properties owned by council members — just primary residences — and the new ones being generated this week will stay consistent with that past practice.

Council member Macon Cowles provided BW with a copy of his map, which is dated February 2010. That map, titled “Council Members Residence,” shows 300-foot and 600foot circles around the house Cowles owned at the time, and includes a list of the other council members and their residential addresses. But it does not, for instance, include the rental property owned by council members Lisa Morzel or those owned by Matt Appelbaum, which they listed in their most recent disclosure forms.

And, of course, it doesn’t include properties that Karakehian and Wilson have ownership interest in. On his disclosure form, Wilson listed the name of the apartment complex in Longmont that he co-owns instead of the name of the real estate trust that actually holds the property. And Karakehian has said he didn’t include his partnerships in limited liability companies (LLCs) that own downtown properties on his disclosure form because they are held by his company, not himself, and they represent his “retirement.”

Cowles says that if the maps don’t show all properties owned, aside from primary residences, they ought to.

“I think they should,” he said, “because the idea is that if a discretionary review comes up within a certain zone, to avoid the appearance of impropriety, that you’re voting in a way that would benefit yourself or hurt somebody else that you had an issue with, you just stay out of the thing.”

The code of conduct language containing the 600-foot rule also seems to support the idea that all property — not just primary residences — should be included on the maps, since it refers to “real property” owned or leased by the council member.

For that matter, the maps should also probably include properties leased by council members, such as property on which Wilson and his partners appear to be paying rent for their consulting business.

Cowles acknowledged that city government has a “structural problem” because the two people who could enforce the council’s conflict of interest rules — City Attorney Tom Carr and City Manager Jane Brautigam — are hired and supervised by council.

“If financial disclosures are not made correctly or sufficiently, there’s nobody there to enforce it,” he says. “The city manager and the city attorney are in a difficult position, because they are employees of the city council, so they’re not the right office to put the hammer down.”

Cowles said that instead of having council members — or one of their employees — serve in that policing role, the city could have a citizens group or committee charged with holding council members accountable for disclosing possible appearances of impropriety.

“It’s important for us to work together, as a group of nine, and not have us pointing fingers at each other about financial disclosures,” he says. “That should be someone else’s job.”

When asked about the allegations regarding Karakehian’s LLCs, Cowles stopped short of casting aspersions on his fellow council member, but agreed in broader terms that all financial interests should be disclosed.

“I think that all properties that a councilor owns a significant interest in should be disclosed, because it provides information to the public that may let the public know whether the councilor has a special interest in it or not,” Cowles says. “We should not permit people to escape the full disclosure by layering entities between themselves and the property interest. That doesn’t look good. That needs to be addressed. I’m not sure our disclosure forms require that property that’s held by an entity be disclosed, but they certainly should.”

Respond: [email protected]